Consternation on a Constellation — Flying from Curaçao to Amsterdam in 1948 (Part 1)

This web page was updated February 17, 2021

Editor’s Note: Ben Guilliamse, the primary author of this web page, was a retired British Columbia Telephone Company employee and part-time bush pilot. For several years, he headed search & rescue operations in B.C.’s Central Interior. Ben was killed on June 7, 2004, when his beloved Cessna 180 crashed shortly after take off from the airport at Prince George, B.C.

According to witnesses and the British Columbia Coroner’s Report, Ben’s aircraft entered cloud at an elevation of 900 feet, and moments later reappeared in a dive under full power. Ben apparently suffered vergito once he entered the cloud, and, like many experienced pilots before him, failed to trust his instruments. The aircraft probably stalled (an airplane is said to stall if it loses lift), went into a steep dive, and plunged into a bog near the end of the runway. Ben never had a chance. His body, still in the cockpit, was recovered with difficulty from a depth of more than 20 feet, moments before the wreckage of the aircraft sank out of sight. An autopsy reveal that he died instantly from “blunt force trauma.”

I miss Ben’s friendship and his well-stocked store of aviation knowledge, stories, and black aviation humour. Especially his humour: As the proud owner of a single-engine Cessna, was especially fond of this aphorism: “When one engine fails on a twin-engine airplane you always have enough power left to get you to the scene of the crash.”

Over the years of our acquaintance, he proved himself to be a generous and helpful friend. My wife, Susan, and I met Ben when we moved to Prince George for my first teaching job, at Wildwood Elementary School on the Hart Highway. He and his common-law wife rented a large house trailer — a mobile home that even came with taillights! — to us; it was conveniently located on a quarter-acre lot just a five-minute walk from Wildwood. Several months later, we decided that it would be wise to invest our money rather than spend it on rent, so we asked Ben and his wife if they were interested in selling their mobile home to us. We were leased when they agreed, and astonished when they said they would apply all of the rent we had paid to a down payment. A couple of years later we sold it for a small profit and moved into a larger home.

Although Ben’s death was violent and untimely, I cannot characterize it as a tragedy: Ben was suffering from age-related health problems that would have soon grounded him. He and his wife had separated a few years before, and she was living her last years in a rest home in Ontario, suffering from advanced alzheimers. Ben’s parents were long dead, he was an only child, and he knew of no other living family members. I have no doubt that Ben would have preferred to die as he did rather than experience a long and lingering death in some “rest home”.

When Ben was 14 years old, he and his parents took an unforgettable — and potentially disastrous — transatlantic flight on a Lockheed Constellation from Curaçao, which had been his family’s home since 1939, to Amsterdam, an adventure he recounts here.

Bob Ingraham

Vancouver

On March 31st, 1939 my parents and I departed from Amsterdam on S.S. Costa Rica, a passenger ship of the Royal Dutch Steamship Company (KNSM). Our destination was Curaçao, an island in the Netherlands Antilles, in the Caribbean Sea about 50 km off the coast of Venezuela.

Escaping the coming war

My father had just finished his studies in pathology and was looking for a suitable position in his chosen field. Amongst his list of applications he had also applied for a vacant position in the government’s Health Services in the Netherlands Antilles. He was successful in having the job awarded to him and he would be stationed in Willemstad, the capital of the island Curaçao. The move also afforded my family the opportunity to escape the coming war in Europe.

As part of his employment conditions, my father would get a yearly vacation period of two weeks for three years in a row. Every fourth year he would be eligible for a vacation period of four months. That extended vacation included the two-way transportation costs for his family to a major destination point of their choice.

Because the Second World War did come, only five months after our move, holidays were not possible until after the war. As my parents were anxious to meet with the surviving members of their families in the Netherlands it was obvious that Amsterdam was their choice for our major destination point. My paternal grandfather had a fatal heart attack on a streetcar in the Hague in 1944. My mother’s youngest sister had a baby boy in 1941 who had died in 1943. There were also two great uncles, who I only vaguely knew by name, who had not survived the “Hunger Winter” of 1944, a result of the despicable Nazi policy of exporting virtually all of the Holland’s agricultural produce to Germany.

Although the war had ended in 1945, there were few suitable passenger steamships owned by KNSM to make the trip to the Netherlands by sea. The majority had succumbed to the war effort and had found resting places on the bottom of various seas and oceans. Among the Dutch ships which were lost during the war was the S.S. Costa Rica, which had brought us to Curaçao. It had become an Allied troop transport; on April 27, 1941, during the evacuation of 2,600 British, Australian, and New Zealand forces from Greece, Stuka dive bombers sank the Costa Rica off the Mediterranean island of Crete. A British destroyer, H.M.S. Hereward rescued all passengers and crew.

KLM resumes Trans-Atlantic operations

The lack of passenger ships was soon compensated for by a post-war resurgence of commercial long distance aviation. Only six months after the surrender of Japan, Royal Dutch Airlines — better known to everyone as KLM — had resumed transatlantic operations, using Douglas DC-4 airliners, which were civilian versions of the military C-54 transports which had been the first large land planes to pioneer Trans-Atlantic air routes during the Second World War.

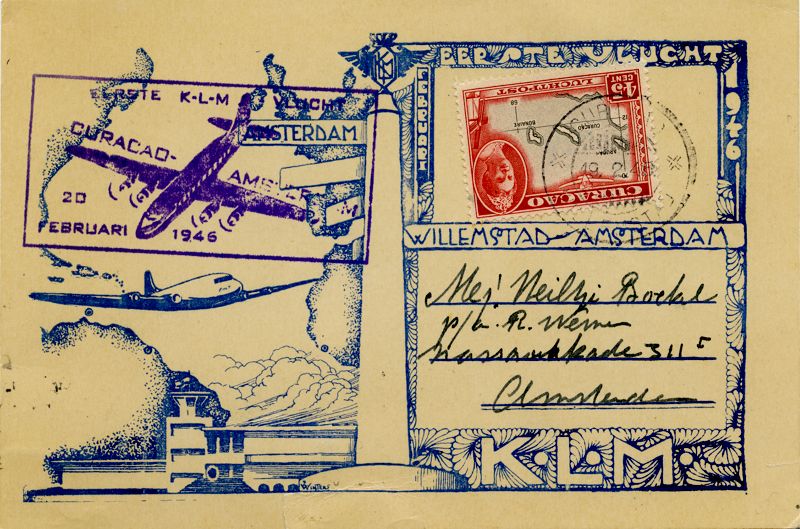

The first of 15 post-war test flights by KLM from Curaçao to Amsterdam, on February 20, 1946, was routed across the South Atlantic via Paramaribo in Surinam; Natal, Brazil; Dakar, Senegal, and Lisbon, Portugal. Later, the KLM route would be changed to cross the North Atlantic via New York City; Gander, Newfoundland, and Prestwick, Scotland.

The residents of Curaçao lost no time in claiming their lost vacation time. Travelling to Netherlands by air rather than by sea suited my parents to a “T,” as the sea voyage would take three weeks in each direction and they were anxious to spend as much time as possible with their relations. We had returned to Netherlands shortly after the war, in a DC-4, but I don’t remember much about that flight.

Our second post-war holiday, which I recall quite well, would be made in a Lockheed Constellation aircraft operated by KLM.

Next, in Part 2: Ben briefly discusses the the history of KLM Airlines and the route his family will take to Amsterdam; he and his parents prepare for their departure from Hato Airport in Curaçao.