The Channel Islands at war — Deportation & Imprisonment

In August, 1941, armed forces of the British Commonwealth invaded Persia (modern-day Iran) in order to secure its oil fields and ensure the safety of supply lines for Russian troops fighting Axis forces on the Eastern Front. German citizens living in Persia were interned by the British.

Hitler, always ready to retaliate against supposed injustice, ordered the immediate deportation of Channel Islands residents who were born in Great Britain to German internment and concentration camps. Lists of those residents were prepared in September and October but the deportations did not take immediately place because of the objections of senior German officials in the islands.

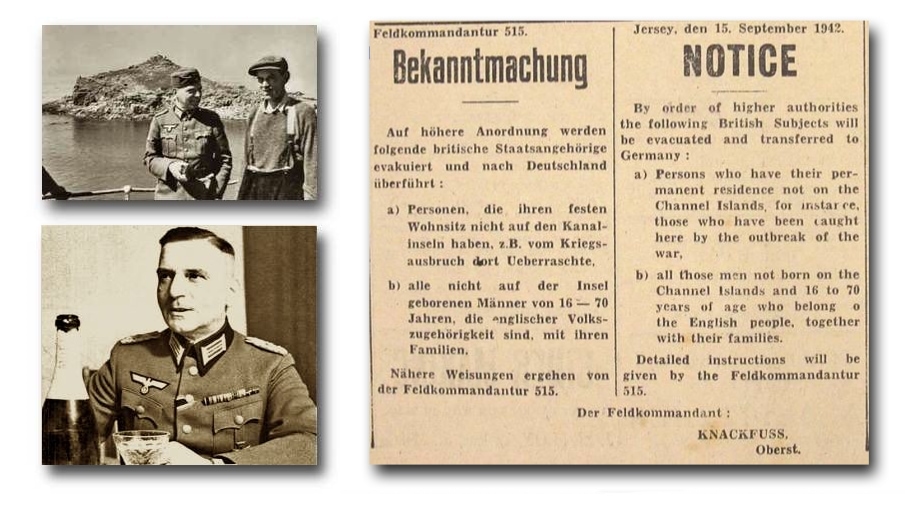

On January 23, 1942, Jersey Feldkommandant Col. Friedrich Knackfüss notified 319 Infantry Division on mainland Europe that he opposed the deportation, arguing that 8,000 “influential” Channel Islanders, considered important by the British government, were providing a shield that was discouraging an attack by Britain. And, in fact, the British were leery of an attack; they had bombed German shipping in Channel Islands harbours, but did not wish to further endanger islanders. Hitler, however, believed that the British would attack the Channel Islands in force: Among the eight inhabited islands, Jersey is the largest and only only 22 kilometers (14 miles) from Normandy and from Hitler’s viewpoint, if no one else’s, would be an ideal location from which to launch an invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe.

Hitler, never one to ignore an opportunity to extend and defend the borders of “Third Reich,” ordered Jersey to be turned into one of most heavily fortified places in the world. Scores of ferroconcrete bunkers and anti-aircraft batteries, hospitals, heavily armed watchtowers, mile upon mile of tunnels, were built by slave laborers imported to the island and and then manned by thousands of German soldiers, all for naught. Since the Allies never attacked the German occupation forces in the Channel Islands, the biggest problem that Germans faced was boredom, not to mention possible starvation.

The Channel Islands have always depended on imports of food from Great Britain, imports which ended with the German occupation. The Channel Islands residents and the German occupation forces alike soon began to suffer malnutrition. By 1944, with the islands largely denuded of firewood by the Germans and suffering shortages of electricity, it became difficult cook meals, even assuming that food to cook was available. Before the war ended, starvation seemed possible, especially after the June 6 Allied landings in Normandy seemed to ignore the plight of the Channel Islands.

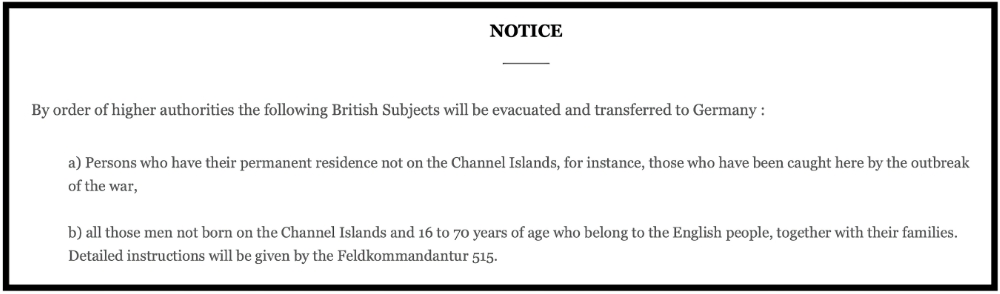

Late in 1942, after the Swiss proposal an exchange of prisoners of war, Hitler realized that his deportation order had not been carried out, and demanded immediate compliance. On September 15, a Tuesday, Col. Knackfüss published a notice of the intended deportation in the Jersey Evening Post.

The English text of the newspaper clipping is presented below for greater readability:

Deportations begin

Knackfüss finally demanded that at least 1,200 Jersey residents should be deported the following day. This was impossible, but when the S.S. La France sailed for St. Malo the following on Thursday night, 280 Jersey residents were aboard. On Friday a further 346 were deported and a third group of 560 left on Tuesday, Sept. 29. In total, some 2,200 people were deported from Jersey and Guernsey to any of several different internment camps in France and Germany. Knackfüss probably lived long enough, but not all that long, to regret his complaints about the deportations.1

Most Channel Islanders were sent initially to Ilag2 Biberach in southeastern Baden-Württemberg, and then were moved on to one of three other camps, depending on their marital status.

Conditions at Ilag Wurzach were less satisfactory than those in other camps; it was located in a three-story 18th-century castle that had previously been a monastery, and the rooms were dark and damp. Ironically, however, internees at Ilag Wurzach and other internment camps were relatively well taken care of, and actually enjoyed a better diet in internment than they had had back in the Channel Islands.

The Jupp Family is interned at Ilag Wurzach

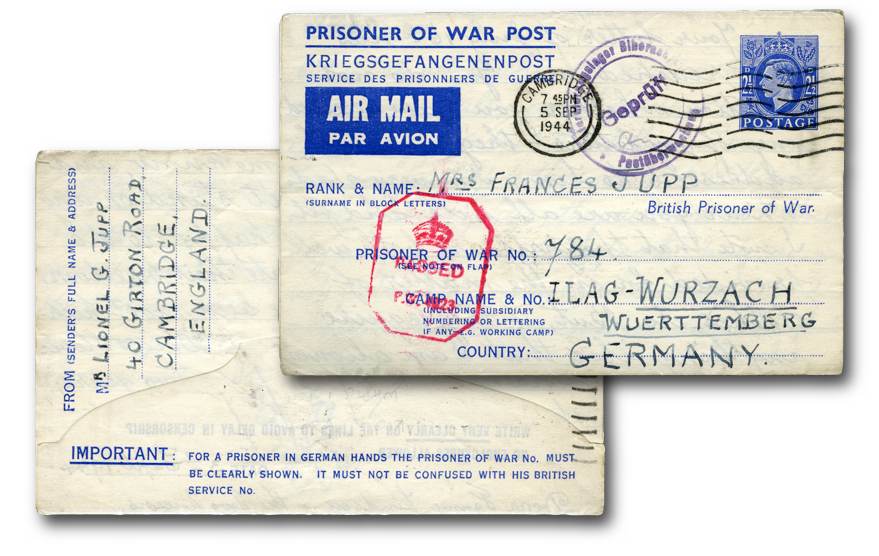

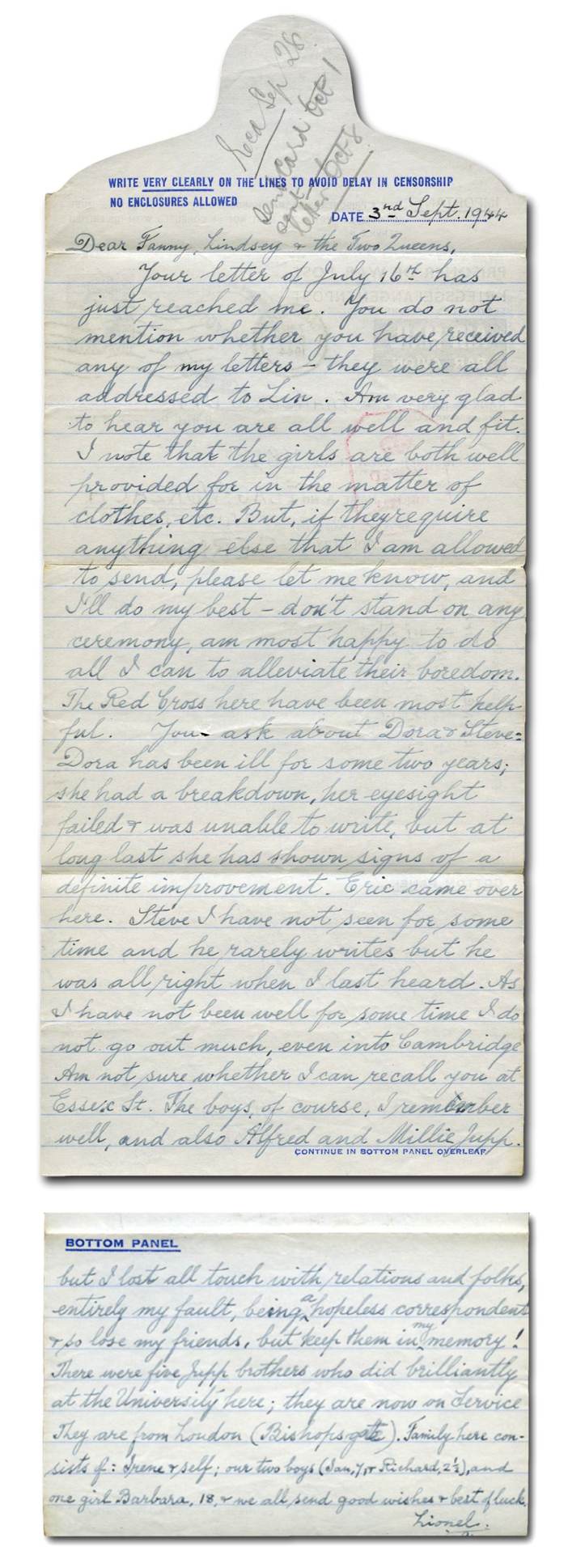

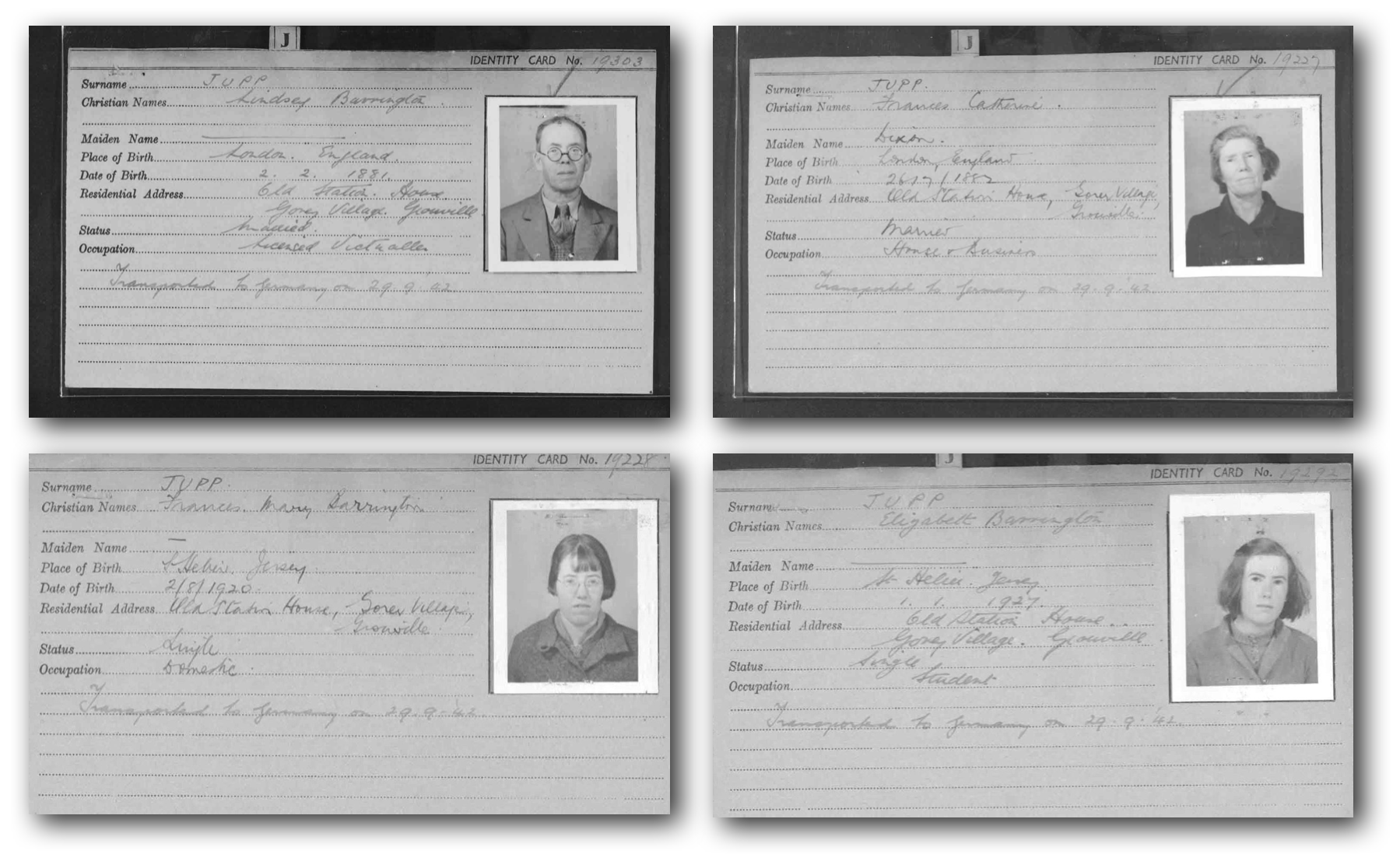

Among the interned Jersey Islanders was the Jupp family — Mrs. Frances C. Jupp, her husband, Lindsey, and daughters Frances M. and Elizabeth. They were among 618 internees transported to Ilag Wurzach, in Wurzach (now Bad Wurzach) in southeastern Baden-Württemberg, on September 29, 1942.

The letter was censored twice, once by the British and once by the Germans; censorship apparently was facilitated by the lack of gum or tape to seal the letter; instead, the flap was simply tucked into a slit in the cover to keep it closed in transit.

Mark Leighton learns about his family’s connection to the Jersey deportations

By chance, long after after this web page was first published, Mark Leighton, who lives “…right up in the far NW Highlands of Scotland — very remote, overlooking the sea and the islands of Skye and Harris,” contacted me by email about his possible relationship to Mrs. Jupp.

Mark had been searching on-line for information about the Jupp branch of his family when he ran across this web page. He had not previously heard of Frances Jupp or her immediate family, and was unaware of the Nazi deportations of British citizens who were born in Great Britain but had made homes in the Channel Islands or were simply visiting friends or relatives.

Our email communication encouraged Mark to dive more deeply into his family’s genealogy, and pass on what he learned to me. He learned a lot, and this web page was a beneficiary.

Mark learned that the author of lettersheet, Lionel Jupp, died in 1951, and that his wife, Irene, became Mark’s maternal grandmother when she married his grandfather, William Carrick. Continuing his genealogical research, Mark was able to fill in many of the missing pieces in the history of Frances Jupp and her immediate family. He learned that Francis and her family lived in Gorey Village, Grouville parish, St. Helier, Jersey, and that Frances and her husband, Lindsey, operated a hotel in St. Helier.

Mark also provided images that any postal historian would consider to be philatelic gold. They included images of identity cards issued by the Nazis. Two identity cards for every person who was being deported, and every other Channel Islander, I assume, were created. The Nazis retained one ID card for each person, and required the islands’ civilians to carry a duplicate ID card with them at all times.

Internees worked to ensure normalcy

For the most part, the Channel Islands internees were treated neither badly nor especially well: wartime conditions meant that neither they nor their German jailers lived “the good life”.

Few photographs of the internment camps appear to have been taken, and most can be seen as little more than propaganda photos. It’s clear, however, that the internees did their utmost to live as normal a life as possible under the circumstances, organizing sports events and forming bands and orchestras.

Death awaited many interned Channel Islanders

Although most deported Channel Islanders were sent to internment camps, a number ended up in some of the most notorious of German concentration camps — Bergen-Belsen, Ravensbruck, Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Theresienstadt. Their “crimes” included slapping a German soldier who made sexual advances, spreading news from the BBC, being an Australian, being an Italian, attempting to escape, sheltering an escaped slave worker, helping a German soldier to desert, owning a gun, radio, or camera, and receiving stolen goods. At least twenty-two of them died in Nazi confinement.

The majority of the Jewish population had been evacuated to the British mainland before the German occupation, and only a small number of Jews were left behind, twelve on Jersey and four on Guernsey. At least eight of them were transported to concentration camps, where they were likely murdered.

Sadly, civilian authorities in the Channel Islands cooperated with the German authorities in identifying islanders for arrest and transport. A British intelligence report from August, 1945 states:

When the Germans proposed to put their anti-Jewish measures into force, no protest whatsoever was raised by any of the Guernsey officials and they hastened to give the Germans every assistance. By contrast, when it was proposed to take steps against the Freemasons, of which there are many in Guernsey, the Bailiff made considerable protests and did everything possible to protect the Masons.

In 1945, British Home Office officials asked Lord Justice Herbert du Parcq to comment on allegations of collaboration within the Jersey and Guernsey administrations. In his comment, Du Parcq criticised the role of the Channel Island governments in the deportation of 2,200 English citizens to internment camps, and some Jews to concentration camps, in 1942, on Hitler's orders. “I think that a strong case can be made,” he wrote, “…that the authorities ought to have refused to give any assistance in the performance of this violation of international law.”3

• The Channel Islands at War — Postage stamps as instruments of resistance: The German occupation of the Channel Islands is documented through postal artifacts of the prewar and wartime periods. The successful efforts of stamp designers to ridicule Hitler and Mussolini and to surreptitiously display their allegiance with Great Britain are highlighted.

• Channel Islands at war — the Red Cross Message Scheme: Channel Islanders were able to communicate with friends living abroad, courtesy of the International Committee of the Red Cross.

• The Channel Islands at War — Col. Rybot’s poetic protest: “An Occupation Alphabet,” a poem written in 1944 by the designer of Jersey’s first occupation stamps, protests the German presence in the Channel Islands as well as the unpatriotic behaviour of some of his fellow islanders.

-

Knackfüss left his post on March 2, 1944 to face court-martial over “defeatist remarks,” his opposition to certain orders issued by superior officers, and his anti-Nazi behaviour. He is believed to have been killed in fighting in Russia in the same year, possibly in command of a German army unit. ↩︎

-

Ilag is an abbreviation of Internierungslager, which means internment in English. Internierungslager were internment camps established by the German Army in World War II to hold Allied civilians, caught in areas that were occupied by the German Army. They included United States citizens caught in Europe by surprise when war was declared in December 1941, citizens of the British Commonwealth caught in areas engulfed by the Blitzkrieg, and British citizens resident in the Channel Islands. ↩︎

-

Quoted in the Dec. 2, 1992 edition of The Independent, a British newspaper ↩︎