The Channel Islands at war — the Red Cross Message Scheme

When Germany occupied the Channel Islands, islanders lost a privilege that they had enjoyed for more than a century: They could no longer send or receive mail from abroad. However, thanks to the International Committee of the Red Cross (I.C.R.C.), it would soon become possible to exchange brief messages with relatives and friends living abroad.

As early as 1870, some Red Cross workers took on the personal responsibility of forwarding messages from during the Franco-Prussian War, a practice that continued through the Boer War and the Turko-Balkin War of 1912-12.

With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the Red Cross officially addressed the loss of war-related loss of civilian postal services. By 1916, a Red Cross message service had been put in place for civilians living in northern France and the Balkins; in May, 1918, the service was extended to include internees in the United States and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria). The message forms that were used were provided by the American Red Cross, and were precursors of those used in the Second World War.

A similar message scheme was operated by the I.C.R.C. during the Spanish Civil War. At the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, the I.C.R.C. obtain the permission of the belligerant nations to introduce a similar scheme.

Channel Islanders get limited communication with relatives, friends

Donald McKenzie, writing in The Red Cross Mail Service for Channel Island Civilians — 1940-45, explains that the British Red Cross Society set up a new department, the Civilian Message Section, in the autumn of 1939, soon after Germany attacked and occupied Poland. By December, 1940, a well-organized message service was in existence in both the United Kingdom and Germany, allowing British nationals who had been interned in Nazi-occupied countries to communicate with their families. But, McKenzie explains, the Civilian Message Section faced a formidable challenge:

The original staff of four had, as one of its duties, the task of summarizing the contents of letters of enquiry into 25-word messages1 upon particular forms referred to as Civilian Messages or Family Messages, and are commonly referred to as Form 61, from the reference number. Before they were forward to the intended recipients, the messages, which could only be of a private or family nature, were checked by members of the Red Cross (perhaps censored would be a more accurate term).

The influx of message requests was such, as many as a thousand a day, that the staff eventually had to be increased from four to 150. Numerous rules had to be followed:

• The text for messages had to be written in block letters and posted or handed in to a Red Cross Message bureau.

• Messages could only be sent to a relative, fiancé, or fiancée (later, friends were included).

• The messages, which could be in English, French, or German, had to be inscribed in block letters or typed on blank copies of Form 61 by I.C.R.C. employees. Carbon copies had to be made.

• Only British citizens were allowed to interpret, inscribe, and handle messages.

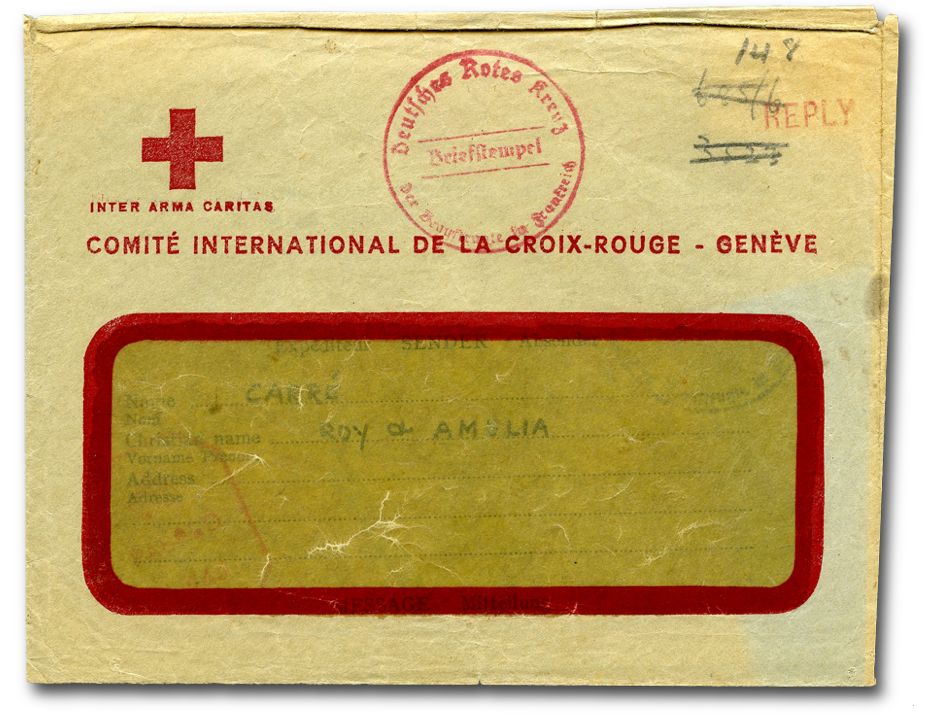

By the end of 1940, the message scheme had been streamlined. People enquiring about their families and friends could purchase copies of Form 61 for a shilling each to complete on their own, then post them to or drop them off at a Red Cross Message Bureau in cities across the U.K. The Red Cross would in turn post bundles of 10 messages to the I.C.R.C. in Geneva, where they would be placed in purpose-designed envelopes and forwarded to the appropriate authorities.

The forms were designed to carry a message to the recipient, who in turn would reply on the same form. The return address was not included (the Red Cross maintained records of each message, including the addresses, which were used to post reponses to the original senders). Both the British Red Cross and the German Red Cross (Deutsches Rot Kreuz) produced their own Form 61s. Interestingly, the British forms were printed in English, German, and French, but the German forms were only printed in German and French.

Like virtually all international mail during the Second World War, most Red Cross messages were subject to censorship in both England and Germany, on their way to and from their destinations. The Germans not only examined the hand-printed or typewritten texts, but often brushed a chemical on the paper to reveal “invisible” messages; the chemical left blue streaks behind. Most forms include multiple handstamp impressions indicating that the contents had been censored, as well as ones indicating which Red Cross bureaux transmitted the messages and received them.

The German form shown below received the same chemical examination by censors as the previously shown form:

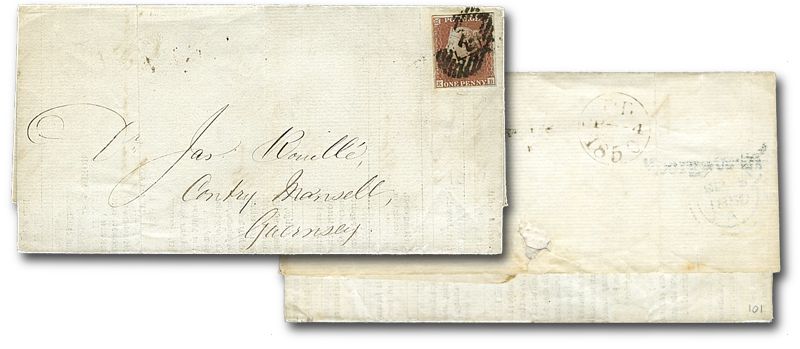

The message scheme was anything but fast. Compare the transit time for mail to the Channel Islands from London in 1850 with that of the Red Cross messages starting in 1940:

• In 1850, it took just one day for the cover shown at the top of this page to reach Guernsey from London, a distance of about 180 miles (290 km); that was probably a normal transit time. One or possibly two more days, depending on sailings from Guernsey to the United Kingdom, were probably required for a reply to be received at a London address.

• In 1940 and throughout the war, it took Red Cross messages an average of four months to reach the Channel Islands from the U.K. and be returned to the original sender. (The example shown above was in transit for a total of more than six months from the time it was sent.)

Convoluted routing

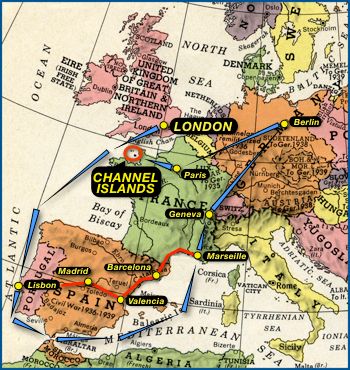

The Red Cross messages were conveyed to and from the Channel Islands on a convoluted route that involved several segments (shown in the map at the right):

• Messages started their journey from the U.K. to the Channel Islands when they were taken or mailed to a local Red Cross bureau, which forwarded them to British Red Cross headquarters in London.

• Red Cross headquarters in London bundled the messages in groups of 10 and sent them to the General Post Office in London for censoring.

• From London, messages were sent by rail to a Channel port, most likely Weymouth in Dorset, then by sea to Lisbon in neutral Portugal. Alternatively, messages were flown directly from London to Lisbon, where they were met by representatives of British Red Cross and/or the I.C.R.C.

• From Lisbon, the messages were sent on to Marseilles either by sea around Gibraltar and through the Mediterranean, or by rail through Spain and Vichy France,2 probably via Madrid, Valencia, and Barcelona.

• From Marseilles, the messages were forwarded to the I.C.R.C. headquarters in Geneva where they were placed in individual envelopes

• From Geneva, the messages were sent either to the German Red Cross in Berlin or to the German Red Cross Directorate in France.

• Strict censorship rules were applied, albeit randomly, before the messages were allowed to be passed into the German Military Post (Feldpost) system and forwarded through France to Paris and on to the Channel Islands, where they were distributed.

Replies to messages or messages originating in the Channel Islands travelled the same route, but in reverse, and were also censored by Germany and England.

You have mail

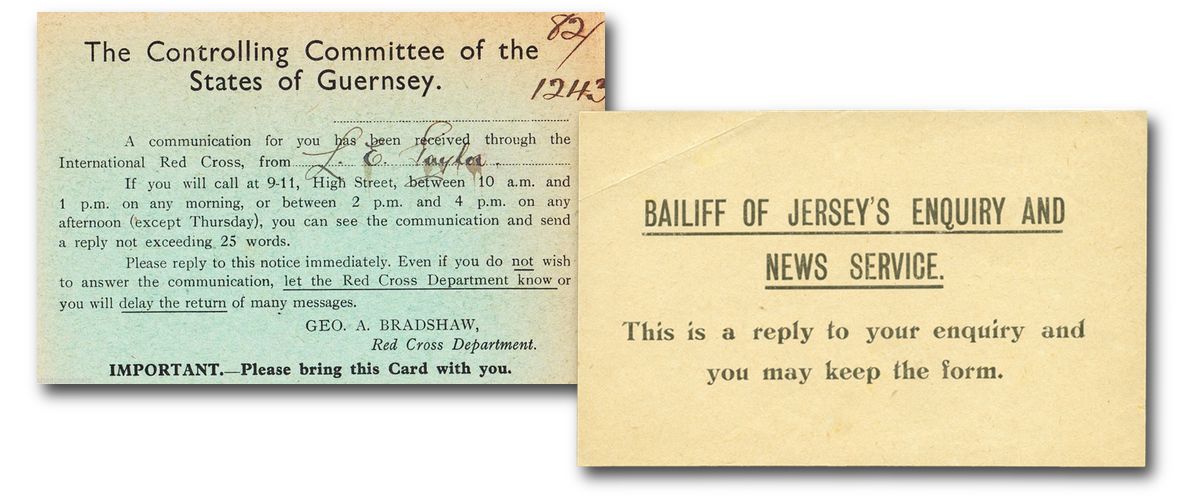

In the early days of the occupation, residents of Guernsey were notified in the local press that they had received Red Cross messages, which could be picked up. Later, postcards known as “Bradshaw Advice Cards,” after George A. Bradshaw, the first supervisor of the Guernsey Red Cross Bureau, were mailed to people who had received messages, providing information about where and when the messages could be picked up. Several varieties of the cards, in three colours, various fonts, and different wording were used. Eventually, the Red Cross messages were simply mailed to the recipients.

In Jersey, messages were posted to the recipients along with a card from the Jersey Bailiff’s Enquiry and News Service, explaining that the message was a response to their enquiry and that they could keep it (all of which seems little more than a way to advertise the services of the Bailiff’s Enquiry and News Service).

Suggested reading:

• The Channel Islands at War — Postage stamps as instruments of resistance: The German occupation of the Channel Islands is documented through postal artifacts of the prewar and wartime periods. The successful efforts of stamp designers to ridicule Hitler and Mussolini and to surreptitiously display their allegiance with Great Britain are highlighted.

• The Channel Islands at War — Col. Rybot’s poetic protest: “An Occupation Alphabet,” a poem written in 1944 by the designer of Jersey’s first occupation stamps, protests the German presence in the Channel Islands as well as the unpatriotic behaviour of some of his fellow islanders.

• The Channel Islands at war — Deportation & imprisonment: British residents living in the Channel Islands, along with some Jews and islanders charged with crimes against the Third Reich, were sent to German internment and concentration camps. Some died there.

-

At first, only 20 words were allowed. ↩︎

-

Vichy France, officially the French State (État français), was the government headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain from 1940–1944. It was based in the small city of Vichy, but Paris remained the official capital of France. From 1940 to 1942, while nominally the government of France as a whole, Vichy only zone in southern France not occupied by German military forces, while Germany occupied northern France.

Following the Allied landings in French North Africa in November, 1942, southern France was also occupied by the Axis on Nov. 11,1942 through the enactment of Case Anton — “Operation Anton” — the codename for the military occupation of Vichy France. It marked the end of the Vichy regime as a nominally independent state and the disbandment of its army, though it continued its existence as a puppet government in occupied France. ↩︎