Mail to Silver City from Vancouver’s Chinatown leads to a story of murder (Part 1)

This web page was updated December 8, 2022

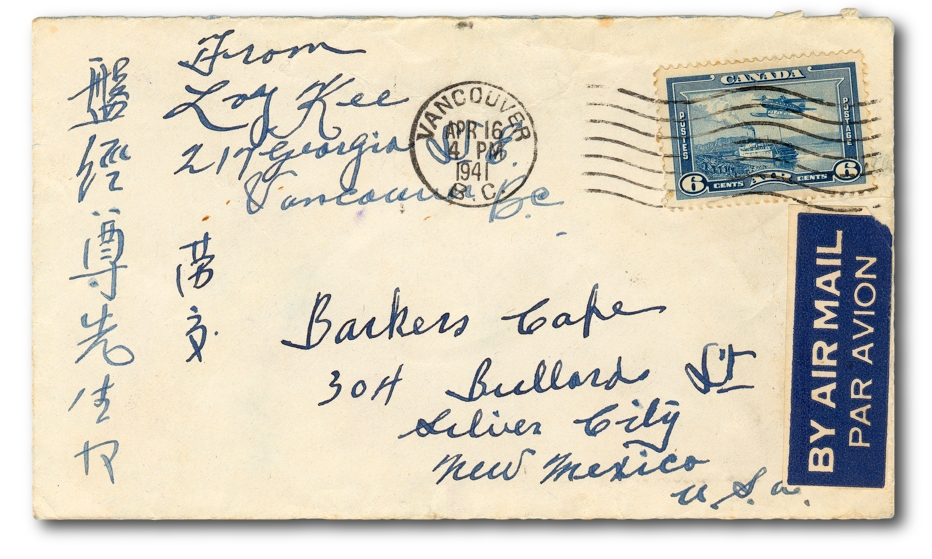

In April, 1941, Loy Key, whose laundry was on East Georgia Street in Vancouver’s Chinatown, posted an airmail letter to Barker’s Café in the mining community of Silver City in southwestern New Mexico. Less than five years later, a Chinese man employed at Barker’s Café would be fatally beaten by two Caucasian men.

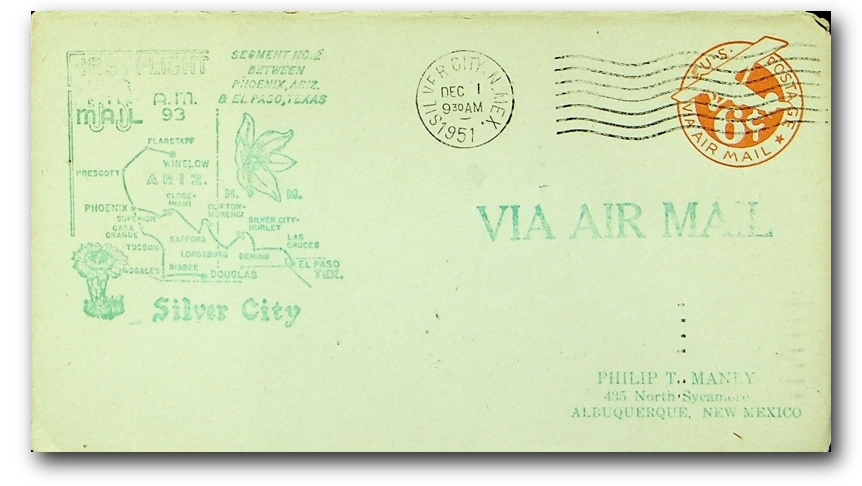

Kee Loy’s airmail cover couldn’t have been flown all the way to Silver City. Because there was no airmail service between Vancouver and Seattle in 1941, the first leg of its trip probably would have been by rail. And Silver City, at the other end of the route, would not have airmail service until 1951 when the Silver City-Grant County Airport opened, as illustrated by this First Flight Cover (FFC):1

As a result, Loy Kee’s letter probably travelled by train on the last leg of its journey to Silver City, probably from El Paso; as late as the early 1960s, mail other than air mail was being transported to Silver City in railway post-office cars.

The airmail segments of the cover’s journey required four different airlines, each serving a specific Contract Air Mail route (designated by the initials “AM” followed by a number) between Seattle and El Paso:

• Northwest Airlines, AM 3, Seattle to Billings, Montana;

• Inland Air Lines, AM 28, Billings to Cheyenne, Wyoming;

• United Air Lines, AM 17, Cheyenne to Denver;

• Continental Air Lines, AM 29, Denver to El Paso.

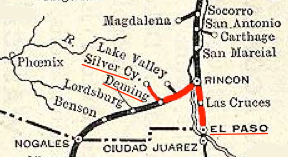

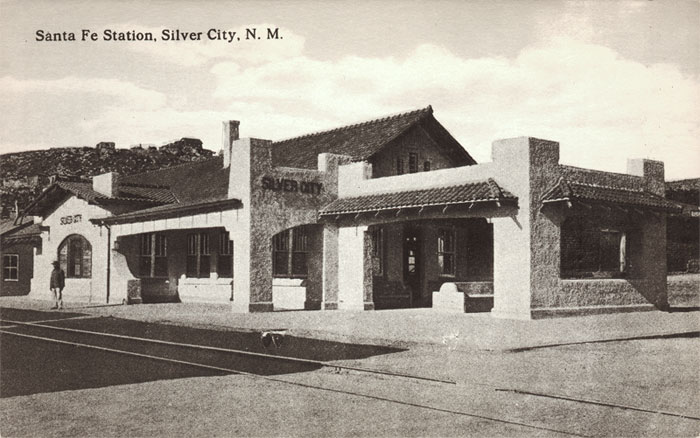

Following its journey by air, the cover was transferred to a train going north from El Paso to Rincon, New Mexico, then to a train going west to Deming, New Mexico, and finally to another train heading northwest to the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway depot in Silver City. The image at the right shows the railway route (in red).

The Chinese characters on the cover are not a Chinese version of the address, but instructions to the recipient. Translated, they read “Please send [to] / Mr. Pan, Jing Zun,” or, in Western parlance, “Mr. Jing-Zun Pan”. Paul Yeung, Cultural Program Director at the Chinese Cultural Centre of Greater Vancouver, noted in an interview that “Pan” is a rare Chinese surname, possibly representative of a minority ethnic group from northern China.

This cover opens a small window on the Chinese diaspora of the 19th and 20th centuries, when Chinese in their millions crossed the world’s oceans to escape the endless cycles of poverty in their own country.

“Gold Mountain” Dreams

The first Chinese arrived in Vancouver in 1858. They called Canada “Gold Mountain” and dreamed of striking it rich in the Fraser Gold Rush, but their dreams soon turned into real-life nightmares of indentured servitude and crushing racism. Vancouver-born author Wayson Choy writes movingly of Chinatown’s early days in his historical novel, The Jade Peony:

Most Chinatown people were from the dense villages of southern Kwangtung province, a territory wracked by cycles of famine and drought. When the call for railroad workers came from labour contract brokers in Canada in the 1880s [to build the Canadian Pacific Railway], every man who was able and capable left his farm and village to be indentured for dangerous work in the mountain ranges of the Rockies. There had also been rumours of gold in the rivers that poured down those mountain cliffs, gold that could make a man and his family wealthy overnight.

“Go to Gold Mountain,” they told one another, promising to send wages home, to return rich or die. Thousands immigrated in the decades before 1923, when on July 1st the Dominion of Canada passed the Chinese Exclusion Act and shut down all ordinary bachelor-man traffic between Canada and China, shut off any women from arriving, and divided families. Poverty-stricken bachelor-men were left alone in Gold Mountain, with only a few dollars left to send back to China every month, and never enough dollars to buy passage home. Dozens went mad; many killed themselves. The Chinatown Chinese call July 1st, the day celebrating the birth of Canada, the Day of Shame….

In the city dump on False Creek Flats, living in makeshift huts, thirty-two Old China bachelor-men tried to shelter themselves; dozens more were dying of neglect in the overcrowded rooms of Pender Street. There were no Depression jobs for such men. They had been deserted by the railroad companies and betrayed by the many labour contractors who had gone back to China, wealthy and forgetful. There was a local Vancouver by-law against begging for food, a federal law against stealing food, but no law in any court against starving to death for lack of food. The few churches that served the Chinatown area were running out of funds. Soup kitchens could no longer safely manage the numbers lining up for nourishment, fighting each other. Chinese men were shoved aside, threatened, forgotten.

During the early mornings, in the 1920s and ’30s, nuns came out regularly from St. Paul’s Mission to help clean and take the bodies away. In the crowded rooming houses of Chinatown, until morning came, living men slept in cots and on floors beside dead men.

Like stepping into China

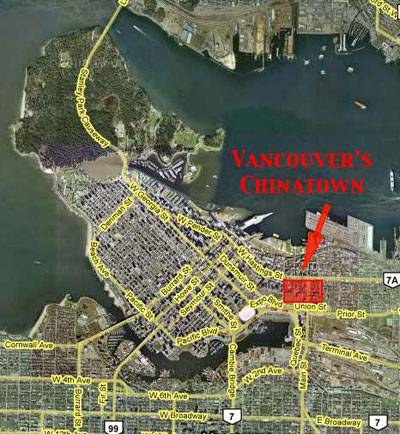

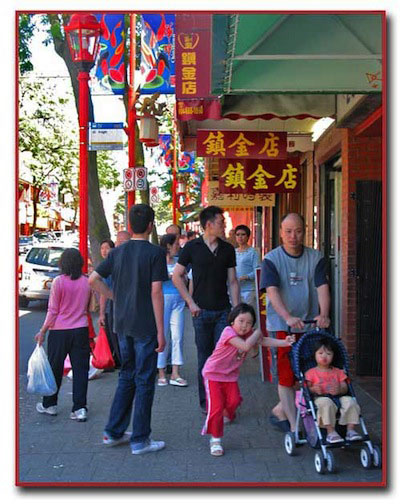

To walk Chinatown’s colorful streets today is like stepping briefly into China itself, although it is more like the China of a few decades ago rather than today’s China. Its streets are crowded with shoppers and filled with sights, sounds, and aromas that to unaccustomed Western senses are exotic. Vancouver, despite growing gang- and drug-related crime, is a statistically safe city, and Chinatown is safer still — only rarely does Chinatown figure in reports of crime.2

It’s just over a kilometre (0.6 miles) from the intersection of Granville and Georgia streets in downtown Vancouver to Chinatown’s Millennium Gate entrance on Pender Street, a short walk or drive from one culture into another. The community survives today as the second-largest Chinese enclave in North America (San Francisco’s is the largest); nevertheless it’s a small area covering only a dozen or so city blocks.

There are relatively few Caucasians to be seen in Chinatown (more in tourist season), and few signs in English (although local business interests are pushing for more). It’s hard to imagine that only a few blocks away is “English” Vancouver, where tourists in their thousands spill into the city from cruise ships to shop in nearby gaudy Gastown and on trendy Robson Street.

Closer still, on Chinatown’s western boundary, is East Hastings Street and its embarrassing, sad ebb and flow of hookers, pimps, drug dealers, and homeless people, who consist largely of Caucasions and First Nations people. (Chinese-Canadians themselves are today for the most part prosperous and no longer suffer the same degree of prejudice of previous decades. Metro Vancouver’s Chinese-Canadians — a third of the population — no longer live exclusively in Chinatown and are integral to Vancouver’s culture, commerce, and politics.)

— Bob Ingraham Photos

Vancouver nearly lost Chinatown in the 1950s: A clique of politicians and developers proposed an eight-lane freeway as an extension of the Trans-Canada Highway to downtown Vancouver. In improving traffic flow into downtown Vancouver, it would have bisected and effectively wiped out Chinatown.

A storm of protest erupted. Vancouver’s Chinese and liberal Caucasian communities, with help from African-Canadians from Halifax who had headed off similar threats against their community, thwarted the plan.

Today, only two kilometres of the Trans-Canada Highway passes within the eastern boundary of Vancouver, with the happy result that the city is not overly plagued with suburban sprawl and inner-city decay (with the exception of that sad stretch of East Hastings Street) and is composed largely of diversified, viable communities. It may also be one of the reasons that downtown Vancouver is one of the the few inner-city areas on the planet that is rapidly growing in population, in part because suburbanites are moving to downtown Vancouver to avoid commuting, which ranges from irritating to nearly impossible.

And what of Loy Kee and his laundry?

And Loy Kee? In Vancouver’s 1941 business directory, he is listed as proprietor of the Diamond Laundry at #217 Georgia Street East. The laundry is long gone, replaced by a parking lot (see photo at right). Enquiries in the area produce puzzled looks and head shakes; a document held in the British Columbia provincial archives records the death of a "Kee Loy," age 74 on September 28, 1949, but provides no other information.

Next, in Part 2: The history of Silver City, New Mexico reflects the story of the Chinese diaspora as it occurred elsewhere in North America. In this case, the prejudices of two Caucasian men lead to the murder of a Chinese immigant, Yat Lim, in the café where he worked.

-

In aerophilately, a branch of philately, a first flight cover, also known by the acronym FFC, is mail that has been carried on an inaugural flight of an airline, route, or aircraft. FFCs are normally postmarked with the date of the flight; a receiving postmark on the back of an FFC proves thast it was actually carried on the aircraft. FFCs routinely have a special flight cachet applied by a rubber stamp. ↩︎

-

An August 2, 2020 update: Sadly, Several Chinese- and other Asian-Canadians in Vancouver have suffered racially motivated assaults in recent weeks, apparently a result of provably baseless accusations in social media platforms that the novel coronavirus that caused the covid-19 pandemic was created and loosed upon the world by Chinese virologists.

An elderly Chinese-Canadian man and a young Chinese-Canadian woman were knocked to the ground, another young woman was struck in the face, and a third young woman was beaten by several young Caucasian men on the SkyTrain. Several cultural icons in Chinatown, including guardian lions at the Chinese Cultural Centre and the famous Millennium Gate on Pender Street have been vandalized multiple times. Many Chinese Canadian citizens have reported threats and suggestions that they should “Go back home!” Vancouver’s Chinese citizens are already home, having been born in Canada, or have entered Canada legally and are either citizens or landed-immigrants, also known as permanent residents, entitled to full protection under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. ↩︎