Mail to Silver City from Vancouver’s Chinatown leads to a story of murder (Part 2)

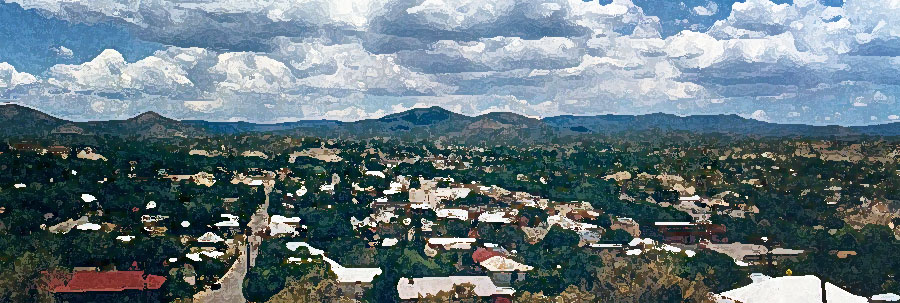

Silver City, a small mining and ranching city in southwestern New Mexico, seems an unlikely destination for a letter from Vancouver’s Chinatown. A glance at Silver City’s history, however, shows that it too has deep Chinese roots.

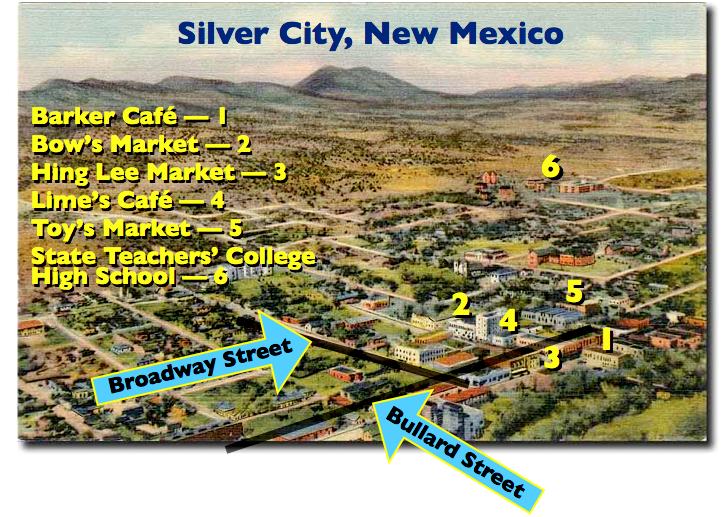

From its beginnings in the 1860s, with the arrival of prospectors searching for silver and gold, Silver City was divided along a cultural fault line separating “Anglos” and “Mexicans” into roughly equal populations. Among the minorities, represented by a few families or individuals, were a handful of Chinese immigrants. In 1949, four of those Chinese, all men, operated Barker’s Café on the east side of Bullard Street in downtown Silver City. The “linen-era”1 postcard shown below provides an aerial view of Silver City and the location of various establishments that are pertinent to this story.

Lured by “Gold Mountain”

Just as gold enticed Chinese men to leave their homes for British Columbia, the same bright metal no doubt lured the first Chinese immigrants to the Silver City area; by the late 1800s, Silver City and the immediate area had become a world-famous centre of precious metal production, not to mention copper, zinc, lead, and molybdenum, and the finest turquoise ever found anywhere.

Silver City’s mineral wealth was mostly denied to its Chinese residents: Wherever they went throughout the world, Chinese immigrants were accepted only grudgingly, if at all, and were normally allowed to engage in only the most menial employment, especially if they were seen as competitors for better-paying jobs.

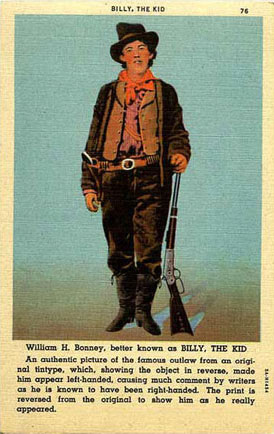

In the mining communities of Western Canada and the United States, Chinese became the cooks, the laborers, the launderers, the grocers. Chinese immigrants were in Silver City as long ago as 1875. The Enterprise reported on Sept. 25, 1875 that a Silver City youth named Henry McCarty was arrested after stealing clothing from a Chinese laundry. Henry escaped from jail and began his career as the infamous desperado, Billy the Kid.

Broken dreams

All too often, immigrant Chinese laborers were able to support only themselves, eking out a lonely living in communities that just barely tolerated them. Some, however, managed to send money back to China, sometimes enough to pay for passage to North America for the wives and families they had left behind in China. Some had never planned to stay in North America, and returned to China, having earned a fortune, at least by Chinese standards. Some returned to China broke and broken. Thousands lost their lives in accidents; during the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railroad, nearly three Chinese labourers died for every mile of track they completed.

All levels of government in the United States and Canada made it nearly impossible for ethnic Chinese immigrants to make new lives for themselves. Some laws virtually forbade Chinese immigration or made it so expensive through “head taxes” that it was an impossible luxury. In neither country did Chinese immigrants enjoy ordinary rights of citizenship until after the Second World War, and were subject to deportation only because they were Chinese.

In larger centres, Chinese immigrants came together in the enclaves that their neighbors called “Chinatowns,” and often organized fraternal societies called “tongs”. Although tongs were originally created for mutual support and protection, especially from other hostile ethnic groups, they often turned to organized crime.

Violent criminal activities among Chinese immigrants began to decline in the 1930s, due to the efforts of middle class or second-generation Chinese activists and Christian missionary efforts. As well, Chinatowns had become a tourist attractions, and the tongs, counting potential tourist dollars, largely turned away from crime and expanded their ranks to include legitimate merchants and businessmen.

Silver City’s Chinese community

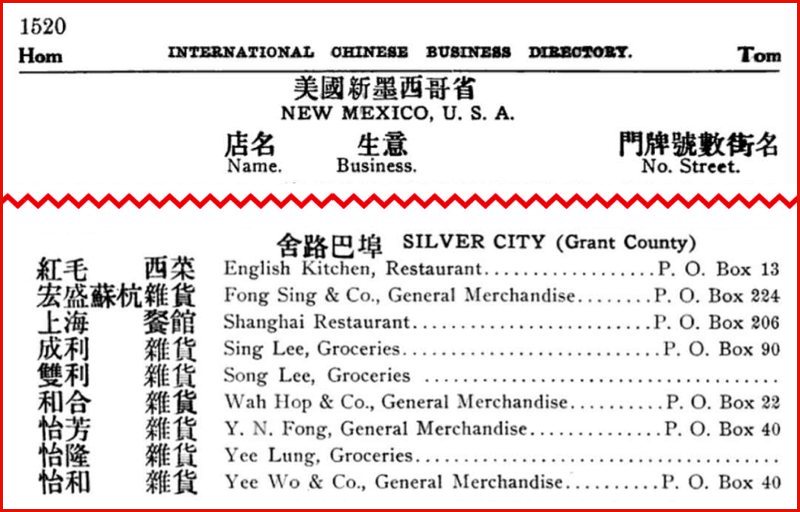

Immigrant Chinese had been resident in Silver City for decades, almost certainly from the city’s earliest beginnings as a mining camp in the late 1800s. In 2018, an email sent to me by Cathy Huang included an image of a page scanned from an International Chinese Business Directory, listing nine Chinese-owned businesses in Silver City — two restaurants, three groceries, and four general merchandisers.

By the time my family moved to Silver City from New York State in 1949, there were no more Chinese-owned general stores, but Chinese families still operated at least three groceries and two restaurants.

Other Chinese residents included “Hing Lee” of Hing Lee Grocery, next to the Big Ditch on the south side of Broadway Street. Bow’s Market was on the north side Broadway Street between Texas and Arizona streets. (I don’t recall ever going into Hing Lee Grocery, but I often bought thick slices of balogna for snacks from Bow’s; my father’s office supply store, Western Stationers, was just two or three doors west of their store.)

~ Image courtesy of Google Street View

The history of the Hing Lee grocery store illuminates the relationship between “Anglo” Silver Citians and their Chinese neighbours. In the 1940s and 1950s, the store was operated by Gau Choon Louie. His grandaughter, Katrina Louie, explained in an email in 2008 how the store came to be called “Hing Lee”:

The store was intended to be called “Heung Lay” (translated as “Make Profit”) and it ended up being called “Hing Lee,” which was easier to write and pronounce in English. The local people in Deming and Silver City got used to seeing my grandfather at the store, so they thought he was Hing Lee. So, “Hing Lee” appears on his gravestone in Silver City, but the Chinese characters spell out Louie, Gau Choon, his married name (Louie Hing was the name he was born with).

Banana cream pie to die for…

A well-known family, the Limes — pronounced Lĭm — operated a small and very popular coffee shop in the Murray Hotel building on west side of Texas Street between Broadway and Yankee streets. Mrs. Sue Lime made fresh banana-cream pie to die for.

~ Bob Ingraham Photo

Included among Silver City’s small Chinese population in the 1940s were four men who owned and operated Barker’s Café on Bullard Street. Jing-Zun Pan, the intended recipient of the letter from Vancouver, may have been one of the owners of the café, or the owners may have been expected to pass the letter on to him.

I remember Barker’s Café, but I was only six years old when my father became editor of the Enterprise, and I don’t recall ever going there.

Herb Toy, the son of Yee Toy, who owned and operated Y. Toy grocery store on Market Street, recalled the owners of Barker’s Café. He explained that they had left their families in China, and that the few Chinese families in Silver City befriended them. Mr. Toy couldn’t recall the names of the Barker’s Café’s owners, but remembered calling them “Uncle” in the traditional Chinese manner.

Barker’s Café, like all of the other Chinese businesses, eventually closed, to be succeeded by various others. In the 1990s, Barker’s Café space was home to a bookstore operated by Doris Rominger.

— Image courtesy of Google Street View

Barker’s Café’s dark past

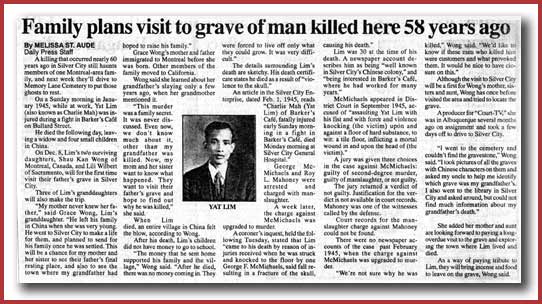

Mrs. Rominger, a long-time Silver City resident and owner of the book store, recalled a fight at Barker’s Café, involving one of its employees, but she was unsure of the details. Further research revealed that there was indeed was a fight, and it resulted in the death of a Chinese man, Yat Lim, one of the café’s owners, known locally as Charlie Mah.

The Enterprise reported on Thursday, Feb. 1, 1945 that “Charlie Mah of Barker’s Café, fatally injured early Sunday morning in a fight in Barker’s Café, died Monday morning at Silver City General Hospital.”

Lim was said to be well-known in Silver City’s “Chinese colony” and “...interested in Barker’s Café, where he had worked for many years.”

Two men, George McMichaels and Roy L. Mahoney, were charged with manslaughter; a week later the charge against McMichaels was upgraded to murder.

A coroner’s inquest was held Feb. 6. The coroner’s report, according to the Enterprise, stated that Lim “...came to his death by reason of injuries received when he was struck and knocked to the floor by one George F. McMichaels, said fall resulting in a fracture of the skull, causing his death.” Lim’s death certificate states that his death resulted from “violence to the skull.”

Yat Lim, who was 30, was survived by his wife and four young children in China. He had planned to bring his family to Silver City once he was settled, and had routinely sent money to them. His death left his family in dire straits, according to Yat Lim’s granddaughter, Grace Wong, quoted in a story in 2002 in the Silver City Daily Press. As a result, his children were unable to go to school.

In a now-defunct web page of the New York Historical Society, titled Chinese-American Inclusion/Exclusion, Grace Wong provided more information about Yat Lim:

My grandfather, Yat Lim (Charlie Mah) left his wife and four children behind when he emigrated from China to Silver City, New Mexico in 1938 for a better life.

His fourth child, my mother, Shau Kan Wong, was about one-year old at the time.

He worked for many years until he saved enough money to invest with other Chinese immigrants in a cafe, called Barker’s Cafe….

He worked very hard to send money back home to his family in China and was planning to save enough money in order to reunite with them in the United States.

A “Not Guilty” verdict, and no court records

McMichaels was tried in September, 1945. The jury could have convicted him of second-degree murder or of manslaughter, or declared him not guilty. The jury returned a not-guilty verdict. Given the tenor of the times — Chinese immigrants were largely disenfranchised — it would have been surprising if the jury had returned a guilty verdict. Chinese had barely been considered human when they first began to arrive in North America in large numbers in the 1880s, and not until the 1950s — too late in the case of Yet Lim — did Chinese immigrants begin to enjoy the same Constitutional rights as Caucasian Americans.

There are no court records or newspaper accounts concerning the disposition of the manslaughter charge against Mahoney, who was called as a witness for McMichaels’ defense.

The cause of the fight that resulted in Yat Lim’s death has never been determined. He is buried in the Silver City Cemetery.

In 2002, Melissa St. Aude wrote a feature story about Yat Lim’s death for the Silver City Daily Press. She had interviewed Grace Wong, who was making arrangements for members of Yat Lim’s family to visit his gravesite.

-

“Linen” postcards, produced from the 1940s into the 1950s, were so named because their surfaces resembles coarse linen cloth. Their images began as monochrome photographs which were hand-painted to be as realistic as possible, and then reproduced on paper with a light “waffle” pattern of ridges which increased the surface area of the postcard and allowed coloured pigments to dry faster so they wouldn’t be absorbed by the paper. The result was richer colour.

Linen postcards remained popular until colour photographic films and improved printing processes started to gain populararity in the 1940s and 1950s. Today, linen postcards are popular collectibles. ↩︎