The Battle of Dien Bien Phu (Part 1) — A centuries-long prelude to war

In the mid-1600s, the most powerful European nations — Belgium, England, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and even Sweden and Denmark — became locked in a high-stakes competition to exploit the human and natural resources of their own neighbours and, well, everyone else.

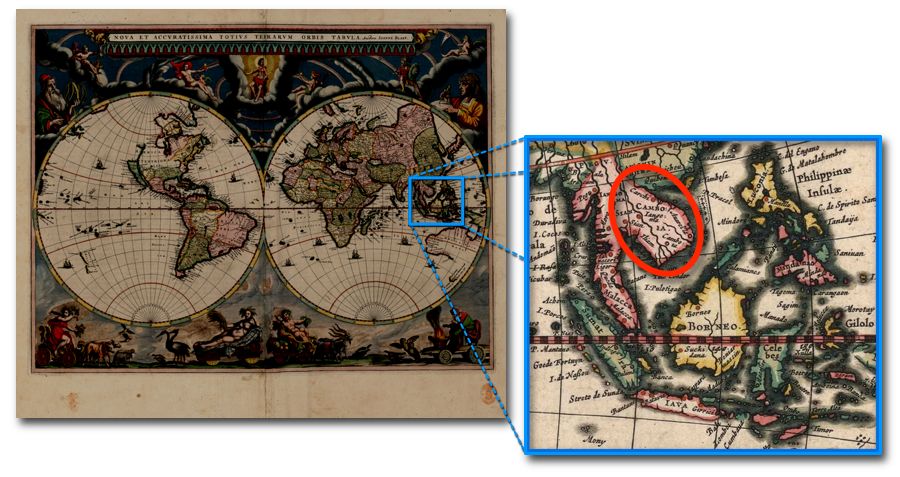

The Americas, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, as well as the islands of the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic oceans, and the Caribbean Sea) were seen as the providers of everything the Europeans didn’t have or wanted more of: precious gems and rare and base metals, and such commodities as rubber, oil, tea, spices, furs, lumber, sugar, rum, silk, perfumes, and carpets. Vietnam, a part of French Indochina in Southeast Asia, was among the most exploited of European colonies.

Mission Civilisatrice

France justified its colonialism by propping it up with the concept of Mission Civilisatrice — “Civilising Mission” — a Gallic form of the English “White Man’s Burden”1 and America’s Manifest Destiny. French imperialists eagerly took on their “responsibility” to colonize “undeveloped” regions in Africa, Asia, South America and the Caribbean where they would introduce modern political thought, social reforms, and up-to-date industrial technologies. In reality, the Mission Civilisatrice was a sham: the real motive for French colonialism was profit at the expense of indiginous peoples, whose quality of life was scarcely considered unless it benefitted France.

Roman Catholicism arrives in Vietnam

French interests in Vietnam date from the mid-17th Century and the activities of Alexandre de Rhodes, a French Jesuit priest who developed a romanized Vietnamese alphabet in 1651 — the Quốc Ngữ — that is still in use today.

European efforts to establish trading posts in Vietnam failed, but Rhodes and other missionaries succeeded in converting up to a tenth of the population by 1700. Vietnam’s Confucian mandarins objected strenuously — Roman Catholic missionaries and their converts were often persecuted and even murdered.

The next century and a half were characterized by a dizzying array of revolts, wars, and conquests, with scarcely a moment when French and other European traders and Roman Catholic missionaries weren’t up to their necks in intrigues to take what they could from the Vietnamese and give little in return.

Paris moves to protect French interests

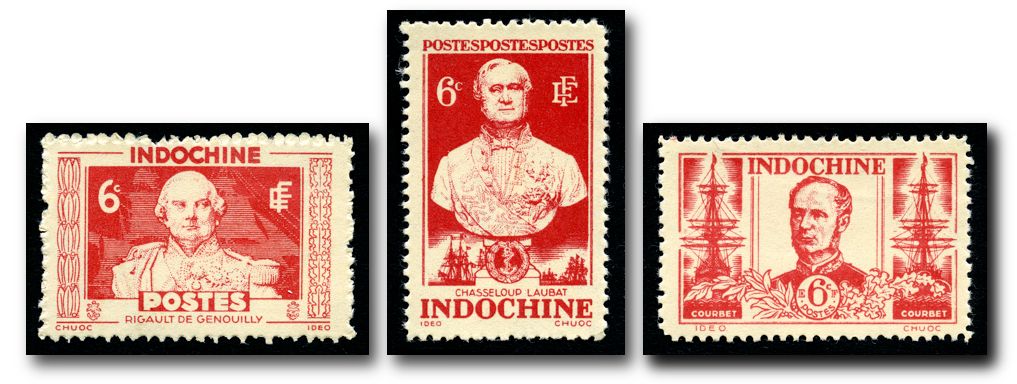

In November 1857, in response to the execution of two Spanish missionaries by the Vietnamese emperor Tự Đức and the failure of a diplomatic mission to Huế led by Charles de Montigny, Rigault de Genouilly was authorised by the French emperor Napoleon III to launch a punitive expedition against Vietnam and create a French protectorate, whether the Vietnamese wanted to be “protected” or not!

The first French attack at Da Nang Harbor failed, but a second farther south was more successful. In 1862, the imperial court at Hue ceded several provinces in the Mekong delta (later called Cochinchina) to France. In the 1880s the French returned to the offensive, launching an attack on the north under the command of Anatole-Amédée-Prosper Courbet. After severe defeats, the Vietnamese accepted a French protectorate over the remaining territory of Vietnam.

• Pierre Louis Charles Rigault de Genouilly (April 12, 1807 – May 4, 1873) commanded French and Spanish forces during the opening phase of the Cochinchina campaign (1858–62), inaugurating the French conquest of Vietnam.

• Count Justin Napoléon Samuel Prosper de Chasseloup-Laubat (March 29, 1805 – March 31, 1873), French Minister of the Navy under Napoleon III and an enthusiastic proponent of Colonial Imperialism, was Minister of the Navy and the Colonies during the attacks on Danang and Saigon.

• Anatole-Amédée-Prosper Courbet (26 June 1827 – 11 June 1885) was a French admiral who won a series of important land and naval victories during the Tonkin campaign (1883–86) and the Sino-French War (August 1884–April 1885).

Colonial rule and resistance

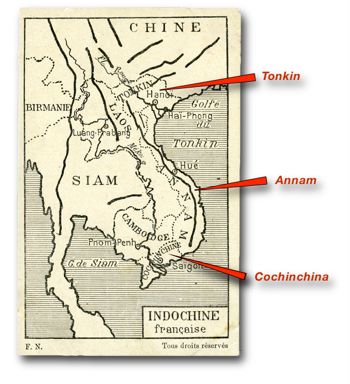

French Indochina was formed in October, 1887 from Tonkin in the north of present day Vietnam, Annam in central Vietnam, and Cochinchina in the south, as well as the Kingdom of Cambodia. Laos was added after the Franco-Siamese War in 1893. Indochina soon became one of France’s most lucrative colonial possessions, part of an empire that spanned much of northern and western Africa, as well as territory in South America (it became French Guiana) islands in the Caribbean and the Pacific.

The French colons understood early on that Indochina, especially Cochinchina and Annam, was so fertile that it could easily become a significant exporter of rice and other agricultural products and minerals. Seizing vast swathes of land, the colons created large rice and rubber plantations, constructed factories, and built coal, tin, and zinc mines. The amount of land used for growing rice almost quadrupled in the 20 years after 1880, 25 gigantic rubber plantations were in operation. By the 1930s, Indochina was exporting 60,000 tons of rubber annually, five per cent of total global production.

Small land-holders were given the options of remaining as labourers on the new rice and rubber plantations or relocating;

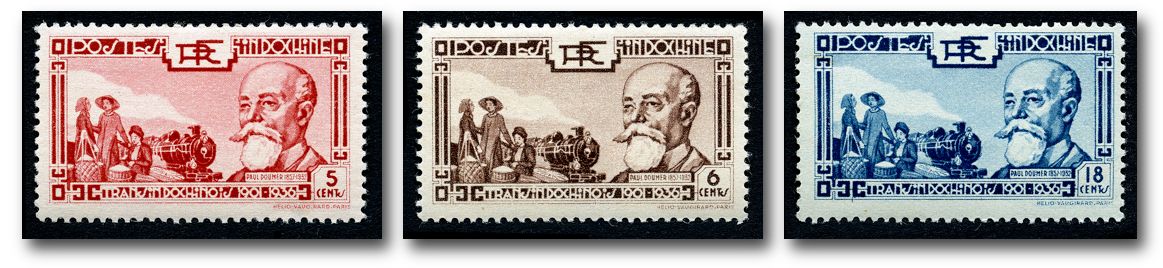

Although improvements in transportation and communication did result from French occupation of Vietnam, its large population of farmers and labourers became increasingly mired in poverty. In the countryside, peasants struggled under heavy taxes and high rents; workers in factories, in coal mines, and on rubber plantations laboured in abysmal conditions for low wages. French colonial laws prohibited corporal punishment, but many officials and overseers enthusiastically beat slow or reluctant workers. Malnutrition, dysentery and malaria were rife, especially on rubber plantations; it was not uncommon for plantations to have several workers die in a single day.

Where there were labour shortfalls, Vietnamese farmers — “coolies” — were recruited en masse from outlying villages, lured by false promises of high wages or seized at gunpoint. They worked 15-hour days for pitifully small wages — some were paid in rice rather than money — without breaks or adequate food and fresh water. Vietnamese peasant-farmers who remained outside the plantations were subject to the corvee, or unpaid labour. Introduced in 1901, the corvee required male peasants of adult age to complete 30 days of unpaid work on government buildings, roads, dams and other infrastructure.

The French colons also burdened the Vietnamese with an extensive taxation system, which included income taxes on wages, poll taxes on adult males, stamp duties on a wide range of publications and documents, and imposts on the weighing and measuring of agricultural goods.

Among Indochina’s lucrative state monopolies rice wine and salt, used extensively by the Vietnamese people, who had always made their own rice wine and gathered their own salt. By the beginning of the 20th Century, they could only be purchased through French outlets at heavily inflated prices.

-

“The White Man’s Burden” was a poem written by the British author Rudyard Kipling, which seems to justify Eurocentric imperialism by summarizing the supposed benefits of subjugating people in “undeveloped” regions of the world. There is some thought, not supported by much of Kipling’s other work, that it was written as satire. If it was intended as satire, its meaning was lost on French imperialists. ↩︎