Corpsman up! — Hospitalman Larry Skonetski in Vietnam (Part 3)

After stopping in Subic Bay in the Philippines for resupply and additional training, and a practice amphibious landing on the Philippine island of Mindoro, the battalion finally landed in South Vietnam on 28 January 1966 as part of Operation Double Eagle. It was the Marine Corps’ first amphibious landing since Korea.

Larry’s experiences in Vietnam echo those of most FMF corpsmen. We all saw a lot of blood, and horrendous wounds, and bodies; we stemmed the flow of blood, immobilized fractures, gave morphine, and offered hope, often under fire. In the eyes of the Marines, we corpsmen were angels, or maybe even gods. In our own eyes, we were just guys trying to stay alive while helping our Marines to stay alive.

On 17 February 1966, I was transferred to 3rd Platoon — Larry’s platoon — in Lima Company, when another corpsman’s enlistment was ending and he was being rotated home. One of the first patients that Larry and I worked on together was Larry’s best friend, Pfc. Mike Neeley.

Mike was just unlucky

Mike was just unlucky — any of us could have could blown apart too. We were bivouacking for the night, enlarging foxholes in the soft red dirt somewhere in Quang Ngai Province. The foxholes had to be large enough to sleep in so we would be safe from mortar fire (unless a mortar round landed right in the foxhole, of course).

The foxholes had apparently been dug some time earlier, by South Vietnamese troops, or perhaps by Australian troops — I found an empty pack of Australian cigarettes. We had been in the area for half an hour or so, each of us stepping in and out of our foxholes as we used our entrenching tools to enlarge them. Mike Neeley stepped one last time out of his foxhole, and onto a mine.

The blast, only 15 yards or so away from me, was stunning in its power, and for several seconds I cowered in my foxhole, unsure of what had happened — it seemed like the end of the world. Then, with debris raining out of the sky, someone called for a corpsman, and I gathered some of my scattered wits. By the time I reached Mike, Larry was already at his side, cool and professional and more than able to make up for my fear. I was trembling like a leaf in a hurricane.

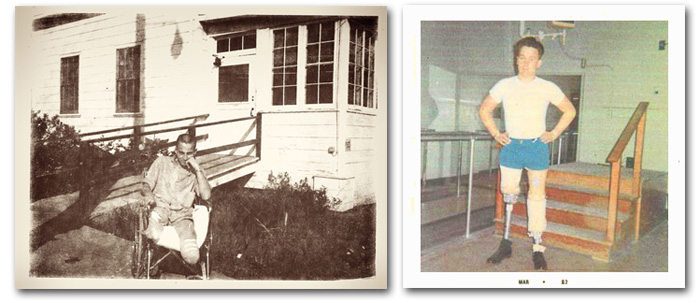

Mike’s lower left leg, what was left of it, looked like bloody hamburger, tapering from the knee to nothing — his left foot had vanished. Mike’s lower right leg had vanished, blown off at the knee; the end of his femer stuck out into the air so cleanly that it could have been used as a model for a medical illustration. Mike was conscious, and wasn’t even bleeding heavily; the blast had apparently cauterized his arteries. Larry and I used our belts as tournaquets around his thighs to make sure that he didn’t hemorrhage.

Larry remembers that Mike tried to sit up. I remember Mike saying that he guessed his career as a competitive swimmer was over.

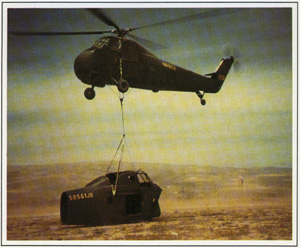

A hazardous nighttime medevac followed. Our radioman contacted the pilot of a Marine Sikorsky H-34 Choctaw helicopter, who was in the air several miles away. The pilot, guided by a Marine on the ground holding a dim flashlight, made a perfect landing within a few feet of us and our patient. Larry climbed onto the chopper to accompany Mike until they reached a field hospital. I stayed behind.

The next morning, a Marine found one of Mike’s big toes about 50 yards away from the site of the explosion. I remember having a hell of a time keeping my fatigue pants up for the next few days, but at least I had legs to put into my pants. Mike survived; I heard later, after I myself had been evacuated to California, that he was being fitted with artificial legs in at Oakland Naval Hospital.

Mike recovered fully, minus his legs of course, and went on to lead an active life, enjoying hunting and fishing, and even obtaining a motorcycle license, just to prove he could.

Larry may have been thought of as an angel by his Marines, but to the VC he would have been seen more as an avenging angel. Under the terms of the Geneva Convention, medical personnel are non-combatants, allowed to carry sidearms only, and to use them only for self-defense. (We corpsmen carried Colt .45 automatics; I had fired one clip with my .45 back in Okinawa, and had completely missed the target with every bullet. No communist soldier was in any danger from me!) The Geneva Convention also states that medical personnel cannot become targets for their nation’s enemies.

F__k the Geneva Convension

The august gentlemen who wrote the terms of the Geneva Convention weren’t in Vietnam, where Marine corpsmen were often targeted, and 638 were killed throughout the 10 years of the war. Larry would have had just two matter-of-fact words for those particular clauses of the Geneva Convention: “Fuck that!” Soon after arriving in Vietrnam, Larry started carrying an M-14 rifle, and early in his tour of duty killed one and possibly two Viet Cong soldiers. He has no remorse, and didn’t kill them out of anger, but simply as a matter of survival: “If I hadn’t killed them, they might have killed me the next day.”

Larry made it through 3/1’s entire tour with only a scratch or two, nothing that would earn him even a Purple Heart. He attributes his good fortune to “dumb luck,” which is probably true, although combat experience usually provides on-the-job training in survival: It was the “FNGs” — the Fucking New Guys — who were most likely to be killed early in their tour of duty.

It certainly wasn’t cowardice that kept Larry alive. Following one incident in which Larry saved a Marine’s life, Lima’s company commander, Capt. James T. Sehulster, recommended Larry for a Bronze Star with a “V” for valor. In an email, Larry described the incident that led to the recommendation:

I don’t even remember what operation it was. We were making a sweep across a lowland area through rice paddies, which of course were full of water with a new rice crop. We sent out a rifle team towards some hedgerows. They drew sniper fire and one, maybe two guys were hit. Their corpsman didn’t move, so I started on out. The rifle fire was coming in like a hail storm and the water was about waist deep. I was getting pretty tired quickly and figured the best way was on top of the dikes. So up I went. We brought the most severely wounded Marine out with his rifle [used] as a splint just like in corps school. Put him on his poncho and hydroplaned him back to cover…. Just our job, you know.

The paperwork for Larry’s Bronze Star never went through — that happened a lot — but just because Larry didn’t get his Bronze Star and never ran for Congress doesn’t mean he wasn’t a hero.

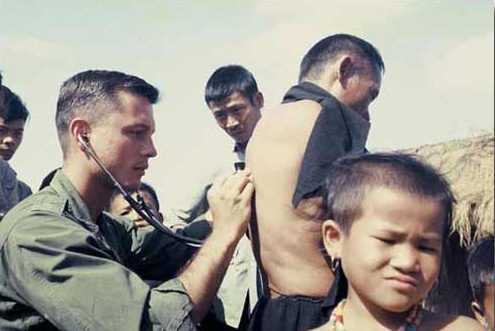

Like other FMF corpsmen in Vietnam, Larry often accompanied the battalion’s medical officers on MEDCAP missions. MEDCAP — the acornym for Medical Civil Action Program — was based on periodic medical clinics held for the Vietnamese in their own villages. MEDCAP was the flip side of combat, a successful if underfunded program that sought to improve the lives of Vietnamese civilians. We never had enough supplies or equipment to diagnosis and treat the wide range of health problems that we encountered, but Larry and his fellow corpsmen and doctors did what they could.

A failing marriage

Larry was surviving Vietnam, but his marriage was falling apart. In truth, it had been falling apart almost since it began. Larry and his wife came from totally different lifestyles and backgrounds, and neither had a clear understanding of the difficulties and responsibilities of married life, and most especially of parenthood. Once 3/1 landed in Vietnam, communication was sporadic, at best. Then one day, after he had been in Vietnam for two or three months, he received not one but two letters from a lawyer in Silver City. He opened the first one. Translated from legalese, it said:

Your wife is suing you for divorce. You have 30 days to appear in court to contest the divorce.

Larry opened the second letter:

Since you did not appear within the required 30 days to contest the divorce from your wife, the divorce is hereby granted.

Subsequently, Larry learned that his baby son was adopted by his father-in-law.

Larry completed his tour of duty in Vietnam in August, 1966. He did a year-long tour on an elderly aircraft carrier, the U.S.S. Yorktown, then trained as a laboratory assistant, ending up at a naval station in Illinois and finally mustering out where he had started 11 years previously, at Great Lakes Naval Station. “I had a little trouble adjusting to the peacetime military, and we both decided to go our own ways.” At the end of his career, he was a Hospitalman Second Class, two steps below Chief Hospitalman, having been reduced in in rank to Hospitalman First Class. He refused to explain the reasons why he had been busted, saying only that it was too embarrassing. He embarked on a new career — long-haul truck driving.