Frontier Airlines flies the mail (Part 1)

With any luck, it might be complete in a few weeks!

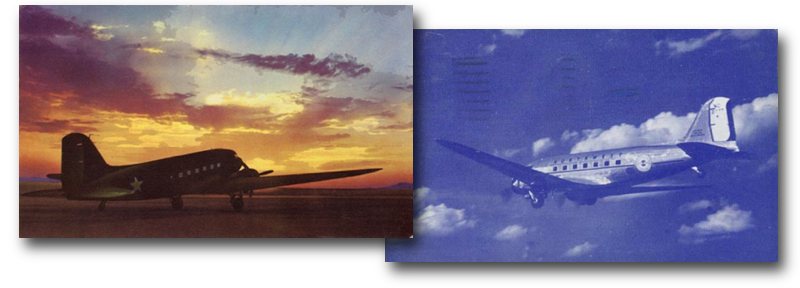

When a Frontier Airlines DC-3 named “Silver City” landed at Grant County Airport in Southwestern New Mexico, on November 30, 1951, it made the front page of the next edition of the weekly Silver City Enterprise newspaper. That’s not surprising — the airport hadn’t existed in an official sense before that day.

!!! IMG FILE '/Users/Bob/Sites/ephemeral/html/imgs/frontier-dc-3-detail-frontier-pc-1953.jpg' NOT FOUND !!!With the addition of the Grant County Airport to Segment 2 of Frontier Airlines’ airmail route, known as AM 93, Silver City and its satellite communities of Santa Rita and Hurley, along with several nearby smaller communities, would for the first time have access to airmail and to fast passenger service to the important larger centres of Phoenix and El Paso, where they could get connecting flights with national and international airlines. Until that day, most communities in Grant County had been far off the beaten path, isolated by their distance from larger cities and by the lack of paved roads.

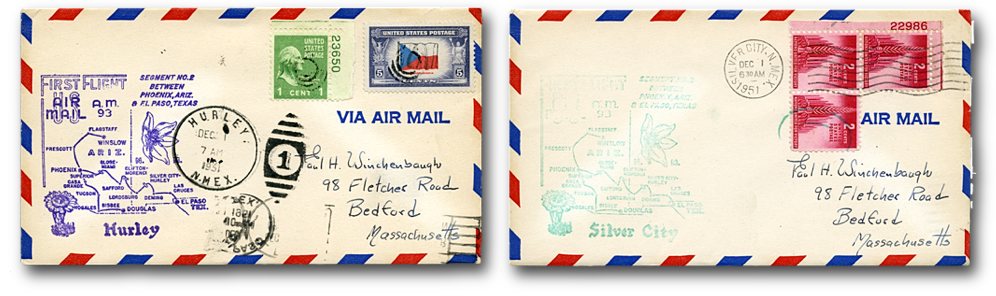

The next day, Dec. 1, the Silver City took off or El Paso, with intermediate stops at Deming and Las Cruces. It was carrying both passengers and mail; the mail consisted mostly commemorative first flight covers.1

First-flight covers typically include a pictorial printed or stamped design or inscription, known as a cachet, to commemorate a postal or philatelic event. Cacheted covers were prepared by the post offices in both Silver City and Hurley for Frontier’s first flights from Grant County airport.2

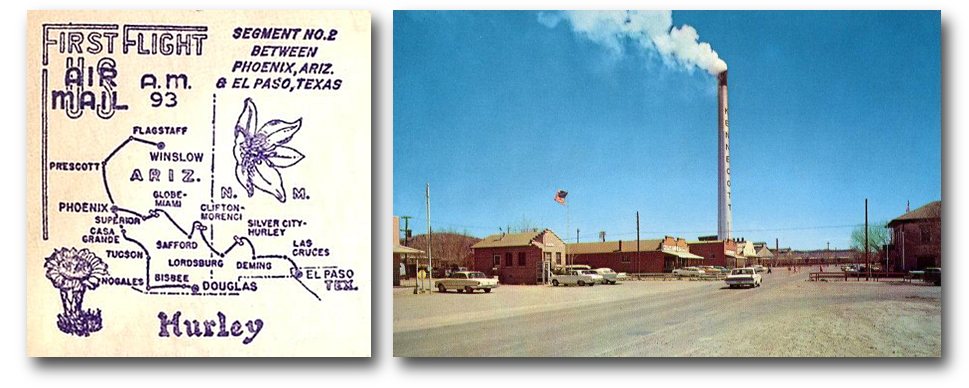

It is unclear why post offices in other communities in the area did not prepare first-flight covers: Santa Rita was almost as large as Silver City at that time, and well known as the location of the world’s largest copper mine, and Bayard was larger than Hurley. Silver City was no doubt selected because it was and remains the hub of commercial activity in Grant County, and Hurley was home to the corporate offices of the Chino Division of Kennecott Copper Corporation, which operated both the mine at Santa Rita and the smelter at Hurley.

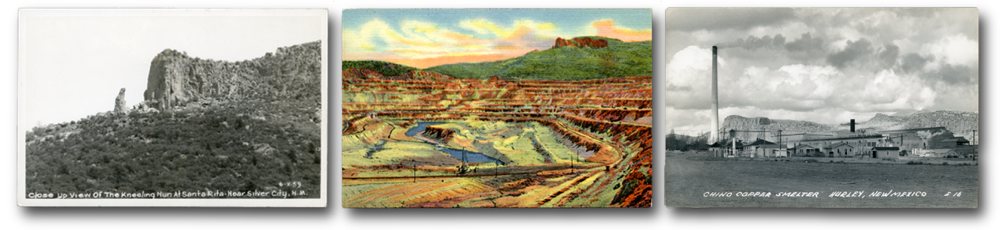

Local citizens took advantage of sightseeing flights on the airliner, which was named Silver City.3 The flights would provide most of the passengers with their first aerial views of such local attractions as the vast open-pit copper mine at Santa Rita, the rock formation called the Kneeling Nun that overlooks the the mine, as well as the copper smelter at Hurley, which boasted the tallest smokestack in the world.

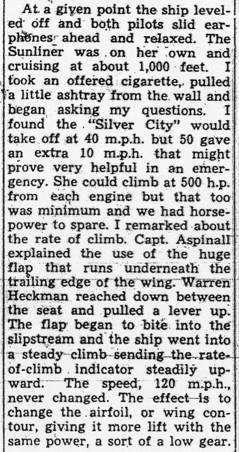

Robert M. Ingraham, father of the author of this web page and at the time the editor of the Silver City Enterprise, rode in the cockpit jump seat of the Silver City on one of those sightseeing tours. In the December 6, 1951 edition of the Enterprise, he wrote a long feature story about his experience, headlined “Front ‘Office’ of Frontier Sunliner is Busy, Interesting Place to Ride”.

In the feature story, he includes details about the operation of the aircraft, from taxiing on the runway through takeoff, cruising, and landing, and comments on

But the arrival of the Frontier Airlines DC-3 was big news for another reason: Although Grant County was a major producer of copper, zinc, lead, molybdenum, and other metals vital to the America, it had always been off the beaten path. Now Frontier Airlines would connect the region with El Paso, to the east, and Phoenix, to the west.

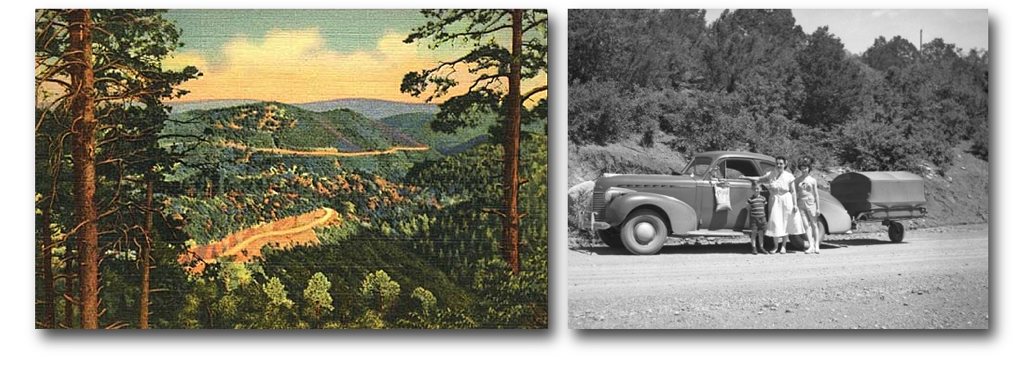

Until 1936, Grant County had just few paved roads and streets within its communities, and none at all connecting it with Catron, Sierra, Luna, and Hildago counties, much less neighbouring Arizona. Driving in any direction meant at least an hour of negotiating bone-jarring, dusty, unpaved roads before reaching pavement.

Driving to New Mexico’s largest city, Albuquerque, involved a 200-mile (322 km) “detour” southeast to Deming, northeast to Hatch, then north to Caballo to get around three north-south trending, contiguous mountain ranges — the Black Range, the Mimbres Mountains, and Cook’s Range. There was a road of sorts through through the Black Range which would have which would cut 100 miles off the trip, but on maps of the time it was labelled “impassable”. It would take several more years before it became passable, at least for the motorist with the courage to face its tortuous curves and steep gradients.

Southwestern New Mexico has always been off the beaten path, despite its importance as a producer of gold, silver, copper, zinc, and even turquoise. A Dutch atlas published in 1908 — the Schoolatlas — includes only one map of the United States, and no maps at all of individual states. Yet Silver City, the current seat of Grant County, is one of only two communities shown in New Mexico (the other is Santa Fe, the capitol). At that time, Silver City was known worldwide as a modern El Dorado, the legendary South American “City of Gold” sought by Spanish Conquistadores. Silver City Grant County (the county seat) and its satellite towns — Hurley, Santa Rita, Bayard, Hanover, Vanadium, Piños Altos, and a few small villages and ghost towns — have played a role in American history that is far more significant than their small size would indicate. Despite their riches, not to mention its rich history, peopled by such notables as Billy the Kid, Geronimo, and the Buffalo Soldiers, the area has remained a backwater surrounded by wilderness mountains, vast forests, and deserts.

The reason? Silver City’s population was estimated at just over 10,000 in 2014, more than the combined population of the rest of Grant County.

The players have included Billy the Kid, Geronimo, the Buffalo Soldiers, General George Pershing, and Harrison “Jack” Schmidt, the commander of Apollo 17, which made the last manned landing on the Moon.

Silver City was founded in 1870, on the heels of the discovery of rich deposits of silver. Stagecoaches provided the fastest means of getting there, but it was a hazardous journey into an inhospitable, remote region. Local Apache Indians naturally resented the hordes of prospectors, miners, and assorted camp followers who descended on the area, and permanently ended more than one dream of finding the mother lode.

By the late 1800s, Silver City had become world famous for the wealth produced not only by its silver mines, but by its gold, silver and turquoise mines as well. In 1883, travellers bound for Silver City could say good-bye to stagecoaches. In that year, narrow-gauge Silver City, Deming and Pacific Railroad trains began rolling into Silver City from Deming (and rolling out again, backwards, because Silver City had no roundhouse to allow a turnabout). Within a year, ownership passed to the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, which converted it to a standard-gauge line.

Then, in the first decade of the 20th Century, its copper deposits, which had been mined since the 1500s, began to be exploited by millionaires based in New York City, notably J.P. Morgan and the Guggenheim family. Since then, the economy of Silver City and what is called the “Central Mining District” has largely depended on the production of copper mined primarily at the huge open-pit mine at Santa Rita, 12 miles (20 km) to the east of Silver City, and smelted at Hurley, 10 miles (16 km) to the east-southeast.

Copper miningToday, Silver City’s economy limps along on tourism, education (it’s the home of the Western New Mexico University),

In 1950, population was 7,022. Hurley, 2,079. Several satellite communities — Hurley, Bayard, Santa Clara, Tyrone, etc. — have a combined population of about 7,500. The nearest larger community, Deming, with a population of 14,600, is 51 miles (83 km); the nearest truly urban city is Las Cruces, 100 miles (160.5 km) south leaving Roman Catholic missions, syphilis, and enslaved Indians in their wake, the area has been off the beaten path. in the 1500s, to their peril; local Apache and Navajo tribes didn’t appreciate their company, no more than they appreciated the hordes of miners and their hangers-on who descended on the area in the late 1800s. Even though Silver City, which became the county seat, once produced more gold (and, of course, silver) than any place in the world, it was always a bit of a struggle to get there. Occasional rail service arrived

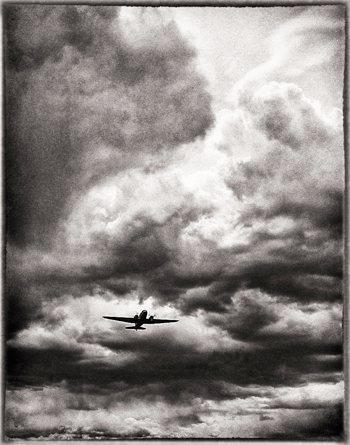

Before the Second World War, travelling by air was a luxury comparable to that of sailing in iconic ocean liners like the Queen Mary. Most people, if they had to travel overland any distance at all, took trains; travel by sea for most people meant long and uncomfortable voyages in small ships.

The war, of course, made short shrift of all luxuries, and the only people who were travelling in large numbers were soldiers on their way to and from combat areas; there wasn’t much luxury on troop ships, and transport planes often didn’t even have seats.

But in the years following the end of the war in 1945, men who had been trained as military pilots began flying commercial airliners. In many cases, the airliners themselves were former military transports converted for civilian passenger and cargo service.

Most of the airliners that began flying in postwar years were larger, faster, safer, and more comfortable than airplanes had ever been before, largely because of technological advances that had come about because of wartime research and development.

The shipping companies didn’t yet recognize it, but their days were numbered. A new age of long-distance travel by air had arrived, and not just for the wealthy: just as trains had connected almost every community in the U.S. by the mid-1900s, airline companies would soon connect those same communities in ever increasing numbers as the second half of the century started. Two of those communities were Silver City and Hurley, in the so-called “Mining District” of Southwestern New Mexico.

Among those pilots was Wayne Aspinall, Jr., son of Democratic Congressman Wayne Aspinall. Wayne Jr. had trained pilots to fly both the B-17 Flying Fortress, which had rained bombs on Nazi Europe, and the first atom bomber, the B-29 Superfortress, which had destroyed most of Japan’s infrastructure through incendiary raids on its major cities and ended the war by dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Early in the 1950s, Wayne Aspinall, Jr. was flying Douglas DC-3s for Frontier Airlines. On November 30, 1950, he landed a Frontier DC-3 “Sunliner” named Silver City at Grant County Airport in Southwestern New Mexico. I was only eight years old at the time, and because it was a Friday, I was in school and didn’t get to see the DC-3 or meet Aspinall. Darn! Nevertheless, on that day his life and mine intersected, sort of. And, although I didn’t know it at the time, DC-3s and Frontier Airlines would play a fondly remembered role in my own life.

Part 1 | Part 2

Rand McNally Auto Trails Map 1925

-

A first flight cover, also known by the acronym FFC, is an envelope that has been carried on an inaugural flight of an airline, route, or aircraft. FFCs are normally postmarked with the date of the flight, and with a postmark of the arrival destination stamped on the back, proving that it was actually carried on the aircraft. FFCs typically include special flight cachet, a printed or stamped design or inscription to commemorate a postal or philatelic event. Because many first flight covers are created as collectables they are normally considered to be philatelic mail. Often, however, they provide the only postal evidence that the flights took place. — Information courtesy of Wikipedia ↩︎

-

Frontier Airline’s first flight from Grant County Airport was designated as AM 93 East. Later the same day, an AM 93 West flight would arrive from El Paso, Las Cruces, and Deming ↩︎

-

In the early and middle-period of the development of commercial aviation, individual airliners were, like ships, often given names. The name Silver City conferred on this particular Frontier Airlines DC-3 was obviously a public relations device. ↩︎