The helmet strap — My insubordination at Camp Pendleton

In October, 1962, when I decided to join the U.S. Navy, the world appeared to be at peace. I assumed that I would enjoy an interesting and safe four-year enlistment. That didn’t happen:

My recruiter promised that I could become a Navy journalist. Never believe a Navy recruiter! The Navy in its wisdom decided I would become a hospital corpsman because I had taken an ecology course in college. I agreed. What I wanted to be was a journalist and photojournalist, but it made sense to me that journalists needed to know a lot about everything, including medicine. I became a hospital corpsman (the Navy’s version of Army and Air Force medics).

At Hospital Corps School in San Diego, I learned that many Navy corpsman have been killed in combat over the years, most of them while serving with the U.S. Marines. I decided right then that I would never volunteer to be a corpsman in the Fleet Marine Force (FMF).1

I worked for two years at the Navy hospital at Yokosuka, Japan. My first job there was helping to deliver babies, and then care for the newborns in the nursery! I also taught English to Japanese members of an English club and enjoyed the company of three young Japanese women.

When my tour of duty in Japan came to an end, the Vietnam War was starting to get serious, and I was…

Shanghaied by the Marines!

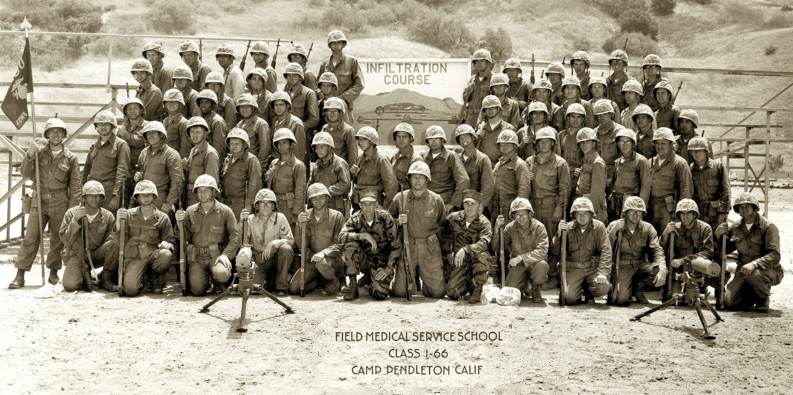

In the summer of 1965, I attended and graduated from Field Medical Service School — FMSS — at Camp Pendleton, California. In theory, I was now a combat-ready Fleet Marine Force corpsmen ready to meet the challenges of the Vietnam War. So much for theory! But this isn’t a war story so much as an anecdote about an unfastened helmet strap and the time I was, well, insubordinate!

It’s easy to spot me in the photograph: I’m just behind the machine gun on the left. You can’t miss me. I’m not wearing Marine fatigues. I’m wearing U.S. Navy dungarees and a light cotton shirt. Therein lies this tale.

At FMSS, a lot of information was packed into a few weeks of instruction:

We treated simulated combat wounds, using the supplies in our “Unit One” medical bags — battle dressings, scissors, adhesive tape, etc. In Vietnam, we would have — and need — morphine syrettes.

We learned to disassemble, clean, and reassembled both the .45-calibre M1911 automatic pistol, which would be our standard sidearm in South Vietnam, and the M14 rifle, which we would be allowed to use if we needed to. (Tests of our proficiency only involved disassembling and reassembling these weapons while blindfolded. I passed the test, but was never trained to shoot either weapon accurately.)

We threw dummy grenades; they had no explosive in them and therefore were disappointing. We slept in pup tents, which we wouldn’t have in South Vietnam; “in country” we had to sleep on the ground, which was often cold and wet. We crawled through a jungle-like obstacle course at night while our instructors detonated small but deafening explosive charges as close to us as possible without killing or maiming us; they didn’t care about our hearing. On another night, we joyously “defended” a high ridge against “enemy” infiltrators, using blanks in our weapons and yelling a lot of nonsense; blank cartridges make a hell of a mess of any gun that fires them.

We sampled field rations, which we called “C-Rats,” a GI term left over from the Second World War when “Type C” rations were introduced. Each Meal, Combo, Individual (MCI) included delicacies like “Meat Balls with Beans in Tomato Sauce” or “Ham and Eggs, Chopped.” In South Vietnam, we would have virtually nothing to eat except C-Rats

One night the corpsmen in my company were preparing to heat and eat our MCIs. Our chaplain, who was training with us, attempted to keep us on the Christian high road: “Boys, you should say ‘Grace.’” Obviously, our chaplain was right: What hungry corpsman wouldn’t be thankful for a concoction vaguely resembling the leftovers that Mom used to serve before payday? We responded with heartfelt enthusiasm, in unison, with rising inflection on the “Yay”: >Rub a dub dub / Thanks for the grub / Yay…God!” All we got from the chaplain for our youthful piety was a dirty look. Marine Corps chaplains apparently weren’t required to have a sense of humour. Nor were they necessarily Christian: My battalion surgeon, Dr. DeShazo, our chaplain got hold of a tommy gun in Vietnam and joined Marine patrols to “hunt” Viet Cong. Ah, Christianity!By the end of our training at FMSS, we looked like Marines and more or less acted like Marines and talked like Marines, but we weren’t really Marines. The Marine Corps, however, cheerfully accepted us into their ranks: they would depend on us for survival in Vietnam, and we in turn would depend on them for our survival Decades later, when my wife and I were walking early one morning on the seawall promenade at Coal Harbour in Vancouver, we encountered another couple whom we assumed to be American tourists. They were perhaps a few years older. I was wearing my 1st Marine Division/Vietnam Veteran baseball cap. As we passed the other couple, the gentleman said clearly, “Good morning, Marine.” Damn that felt good!

Where is my uniform!?

Throughout my training at FMSS, I was an odd man out in terms of my uniform. Of the 64 corpsmen in my company, I was the only one I recall without Marine fatigues, which at that time were made of heavy, olive drab cotton sateen. (In our graduation photo, one man in the top tow, has a light-toned shirt, but it has no Navy rating patch on the left shoulder like mine.)

Perhaps I just wasn’t big enough. At 171 cm (5'7"), I was certainly one of the smaller men in my company. Maybe there were no uniforms that fit me, or none arrived before my company was graduated early as a result of orders from Washington to speed up training for the build-up of American troops in South Vietnam. In any event, I wasn’t issued with a Marine Corps uniform in my size until I’d been transferred from FMSS to the 1st Marine Regiment. That caused some problems, because my uniform — the “undress blues” Navy work uniform of that time (light chambray cotton shirt and light-weight denim trousers) — wasn’t designed for ground combat. That became obvious on our last day of training.

On that day, we had crawled, wriggled, and squirmed across a sandy “beach” strung with low strands of barbed wire and raked by loud blasts of machine-guns firing bullets. Real machine-gun bullets! What a miserable experience! I ended up hot and sweaty, with sand inside my undress blues, inside my skivvies, and probably inside every body orifice! Then, without a break, we went straight to our last exercise, live firing of the M14. That was where my undress blues really let me down and led to my mutiny, brief though it was.

The M14: Not a weapon for wimps

The M14 is no weapon for wimps. I had fired other military rifles, a German 8mm Mauser that belonged to an older friend when I was in high school (that was no rifle, it was a cannon!) and the M1 Garrand in boot camp. I was prepared for the stunning kick of the M14, but I wasn’t prepared for what happened to my right elbow and to my cotton shirt.

I am “semi-ambidextrous”. I naturally shoot a rifle from my left shoulder; in the prone shooting position, my elbows rest on the ground. I was more or less prepared for the first shot, which drove my whole body backwards, proving Newton right: for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. As the M14’s heavy bullet blasted out of the muzzle at supersonic speed, my body (and my elbow) were slammed backwards into the sand. And that caused a problem!

My light cotton shirt sleeve provided no protection. None. I might as well have been sleeveless. Grains of sand shredded the cotton and were instantly embedded into my elbow. By the time I finished shooting — just one 10-round magazine as I recall — blood was dripping from my elbow and my shirt was ruined. All because I was dressed like a swabbie, not a Marine. My grad photo shows me as I was: hot, tired, sweaty, dirty, and in a murderous mood. Good thing I didn’t have any cartridges for my M14.

“Ingraham, fasten your helmet strap!”

!!! IMG FILE '/Users/Bob/Sites/ephemeral/html/imgs/helmet-strap-iwo-jima.jpg' NOT FOUND !!!The company commander (a chief hospital corpsman) had told all of us to fasten our helmet straps. We were in the Marines Corps, after all, and the military is all about uniformity. I’m sure that the Marines who stormed ashore on Iwo Jima had first passed inspection to ensure that their helmet straps were fastened. Or not — see photo at the left. Anyway, I ignored him. He glared at me. He gave me a direct order. “Ingraham, fasten your helmet strap!” I continued to ignore him. This was a new experience for me. I had never been insubordinate in my entire life. Not once. If anything, I could have been the poster boy for the co-operative, patriotic American spirit, but enough was enough: I ignored my company commander and I didn’t fasten my helmet strap.

Surprisingly, the snapping of the graduation picture ended the episode. My company commander never mentioned the incident, and I mostly forgot it. Soon, I was ordered to report to the First Marines. After a few days of cooling my heels in a holding company, I got orders to report for duty with Mike Company, Third Battalion. And I finally received my Marine uniforms, except for the dress blues. I now looked like a Marine, at least. But the story of the unfastened helmet strap wasn’t over….

Later that summer, our battalion shipped out for Okinawa for additional training. On January 28, 1966, we waded ashore in Quang Ngai Province, South Vietnam, at the beginning of Operation Double Eagle. In mid-February, I was transferred to Lima Company. And I was, of course, wearing marine utilities!

On March 5, Lima and Mike companies were ambushed by combined North Vietnamese and Main Force Viet Cong units on the second day of Operation Utah; early in the battle, a communist rifleman shattered my right femur from a distance of only 20 or 30 metres (65-98 feet).

About an hour after I was wounded, I was loaded onto a Sikorsky UH-34D Seahorse helicopter, flown by the Red Lions 633 squadron, and evacuated to the 3rd Medical Battalion field hospital at Chu Lai. I hadn't had any morphine,* so I was alert enough to recognize the chief hospital corpsman who was in charge. It was him, the chief petty officer of FMSS days, my commanding officer during FMSS days, whose helmet-strap orders I had angrily ignored. Was the worst day of my life about to get even worse? I was going to be evacuaated to the hospital ship, U.S.S. Repose. Would he also have me court martialled?

If the chief recognized me, he showed no sign. I don’t recall if he even spoke to me, but then I wasn’t feeling very conversational, and my small rebellion back at Pendleton paled to insignificance compared to the challenges we all faced in Vietnam: In 1966, 3rd Medical Battalion treated nearly 6,400 wounded marines and sailors; only 214 would die of their wounds. The battalion received a Navy Unit Commendation for its work; an excerpt from their commendation reads,

The officers and men…despite shortages of personnel and medical supplies — and adverse conditions of heat, humidity and monsoon rains — succeeded in reducing the mortality rate of wounded U.S. Marines to the lowest figure in wartime history.

As one of the wounded, I am grateful for the expertise of that chief petty officer and the other corpsmen who worked with him. He checked my vital signs, and supervised the changing of my dressing and splinting of my mangled leg, all steps that would ensure my healing. Soon I was being ferried by helicopter to the hospital ship for surgery and the beginning of my nine-month recuperation.

In the grand scheme of things...

Looking back — way back! — my unfastened helmet strap was of little importance in the grand scheme of things. But my defiance that day did a lot for my self-esteem, and perhaps helped to prepare me for the ordeal that lay ahead in South Vietnam.

-

The U.S. Marine Corps, as the amphibious landing force of the U.S. Navy, does not have its own medical personnel. Instead, Navy hospital corpsmen, nurses, and doctors are seconded to the marines for training in land-combat operations. ↩︎