DRAFT

Idlewild in sight — At flight’s end, safety eludes an Italian airliner (Part 2)

Crossing the North Atlantic in stylesssxxxxxxxxxx

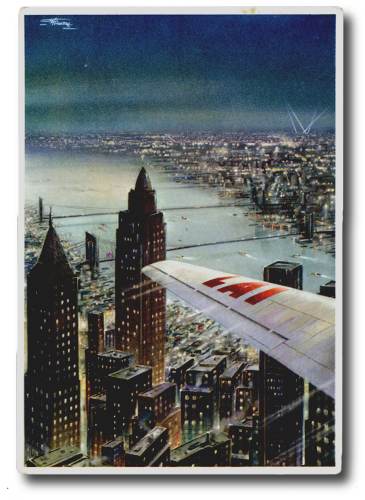

As LAI Flight 451 approached New York City, everything seemed to be in order. The aircraft’s four powerful Pratt & Whitney "Double Wasp" radial engines were working faultlessly. The pilot, co-pilot, and flight engineer on the flight deck were well rested, at least in theory: LAI routinely assigned two flight crews to its transatlantic flights, comprised of two pilots (captains), two co-pilots (first officers), a radio operators, two engineers to oversee the airliners’ capricious radial engines as well as the its electrical, hydraulic, and heating systems.**

On Flight 451, one crew would have flown from Rome to Shannon, then turned the plane over to the second crew for the flight across the North Atlantic to Gander. The first crew would likely have rested in a small crew cabin for the flight across the North Atlantic until it was time for them to take over the cockpit again for the relatively short hops from Gander to Boston and on to New York City. Presumably, the stewards worked alternate legs of the trip, but the radio operator and hostess were apparently on duty throughout the flight.

Flight 451’s passengers, unlike the flight crew, did not have the luxury of their own bedrooms, but Linee Aeree Italiane, facing competition from other airlines, not to mention ocean liners, went all out to ensure that its passengers might become repeat customers. The most useful “tool” in their airline toolbox? The ability to move from Point A to Point B at high speed. LAI, like all of the world’s major airlines, was dedicated to fast flight at least as much as it was dedicated to safe flight. That dedication fell right in line with the transportation industry’s search for the Holy Grail — the fastest possible time to move passengers from any Point A to any Point B, anywhere on earth. LAI Flight 451 was rapidly nearing the end of its long flight from Rome. What could go wrong? Lots, actually:

Faster, faster, until the thrill of speed overcomes the fear of death

Hunter S. Thompson, a “counter-culture” journalist of the 1960’s and 1970’s, wrote first-hand about the thrill of riding motorcycles. He clearly understood the nearly erotic nature of the quest for speed when he wrote, “Faster, faster, until the thrill of speed overcomes the fear of death.”

Before the Industrial Revolution began in the late 1700s, people could move or be moved only as fast as their feet could take them, as their horses could run, as boats and ships could carry them. A fast-moving river might move them along at a breathtaking speed. If people went sledding, tobogganing, or skiing, gravity might pull them down snowy grades at a good clip, but such brief excursions never took them much beyond and below their starting point, and the speeds they reached were snail-paced by comparison with today’s record-slashing Olympic bobsled, luge and skiing events. The fastest anyone could go in pre-industrial times was by falling or jumping from a cliff or tall building; a person taking even a “modest” plunge of only 10 metres (the height of a three-storey building) would strike the ground — •Splat! — at about about 41 kilometres per hour (25 miles per hour). But with the advent of the Industrial Revolution and its steam engines in the late 16th Century and early 17th Century, people began moving. A lot faster without the necessity of falling from high places.

• In 1830, when steam locomotives were began transporting passengers in the United States, the Lancaster, Ohio school board stated with one voice that if the trains’ “Satanic” speeds of 24 kilometres per hour (15 miles per hour) would lead immortal souls to Hell.

• In his historical novel novel The Great Train Robbery, author Michael Crichton notes that trains in the 1850s flew along the tracks at 87 kilometres per hour (54 miles per hour,) an “unholy” speed according to some observers. In one of the novel’s most memorable scenesone of the robbers struggles forward across the rooftops of the cars as the train pounds along the track at, presumably, its top speed.

• In 1903, the Wright Brothers first launched their Wright Flyer from a sand dune at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, with Orville Wright at the controls. The flight was slow and brief: the aircraft reached an airspeed of 58 kilometres per hour (36 miles per hour) and landed just 37 metres (120 feet) beyond its take-off point. Nevertheless, it was the world’s first flight by a powered, heavier-than-air aircraft under the control of a pilot, and that was enough for aviation-minded visionaries to imagine a world shrunk a thousandfold by flying machines streaking through the sky, spanning oceans and continents, and carrying thousands of passengers.

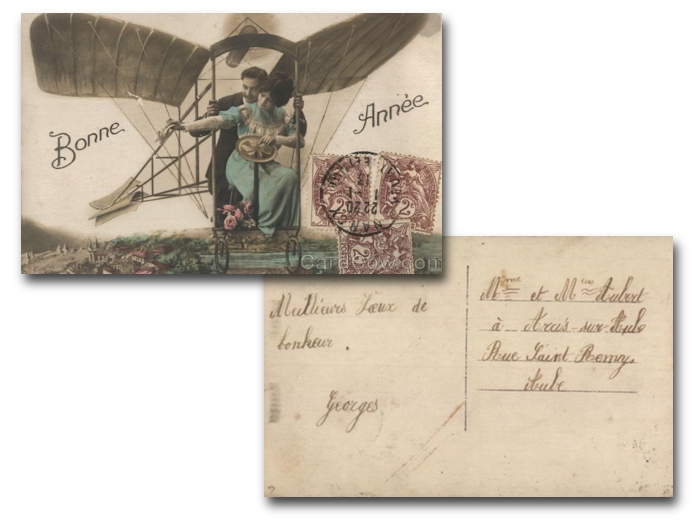

The Wright Brothers weren’t the first aviators to attempt mankind’s first powered, heavier-than-air flight, and they were hardly publicity hounds. Only a handful of people witnessed their first powered flight. But similar technologies have a way of being developed independently, almost in unison, across the world. Over the next decade, scores of inventors launched, or tried to launch, their own flying machines into the air, impressing everyone with their bravado if not their success. Dreams of flight came to nearly everyone, and entrepreneurs were ready to take full advantage of those dreams. Picture postcards from those hopeful days reveal a naive enthusiasm for flight.

The world’s first airline takes flight

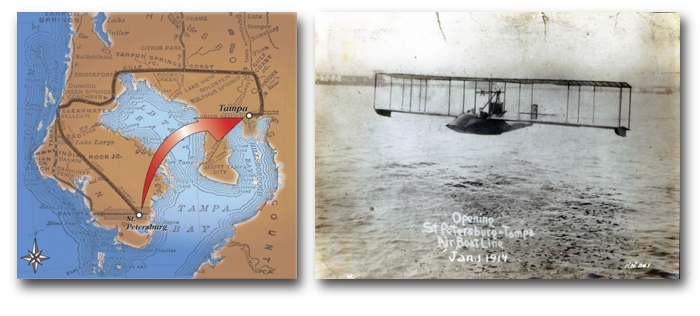

Among the visionaries who saw a future world with skies filled with flying machines was an American, Percival Fansler, who convinced his associate, aircraft designer Thomas W. Benoist, to develop the world’s first airline, the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line, or SPT Airboat Line, using a Benoist Model XIV Airboat. The Benoist Airboat could carry just one passenger across Tampa Bay between St. Petersburg and Tampa at the then-amazing speed of 103 kilometres per hour (64 miles per hour). Passengers who were willing to buy an Airboat Line ticket for 5.00, ($135.27 in 2021) could land in St. Petersburg (or Tampa) about 20 minutes after starting their flight in Tampa (or St. Petersburg). They did save time: the trip would consume 12 hours by rail, or 20 hours by car.

The first scheduled flight between the two cities departed shortly before 10:00 a.m. on January 1, 1914, piloted by Tony Jannus1 and carrying former St. Petersburg mayor Abram C. Pheil as its passenger for the 35 kilometre (22-mile) flight. Pheil had paid $400.00 ($11,000 in 2021) at auction for his ticket .

The Airboat Line was grand in its conception — Fansler and Benoist believed that airlines could be popular and profitable — but troubled in its inception. Few aircraft at that time could carry more than two or three passengers, and few people were willing to risk leaving terra firma for any reason, especially in flimsy, noisy contraptions made of sticks, cloth and wire and powered by noisy engines that sprayed oil over pilots and passengers and were flown by the seat of the pilot’s pants and the limited assistance of a primitive compass and altimeter.

The St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line operated for only four months, until winter residents began heading back north and the airline lost its subsidy from the St. Petersburg city government, but the die had been cast: Nearly every developing country in the world started lusting for their own national airlines.

Provide fast, safe, comfortable travel & they will come (first, however, they’ll send letters by mail)

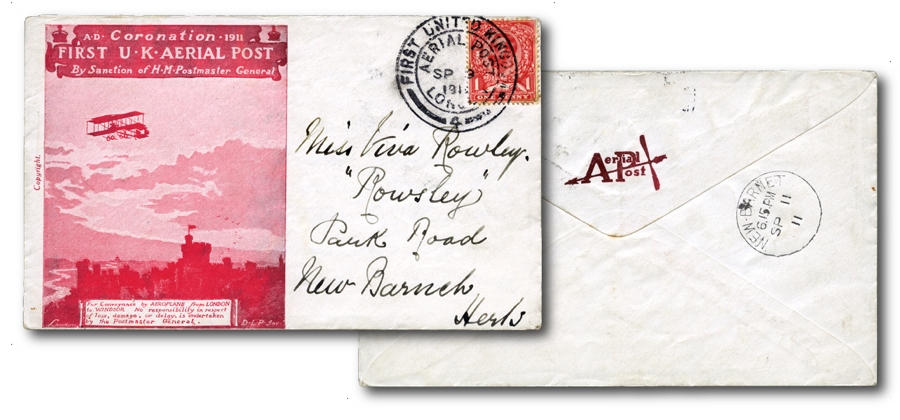

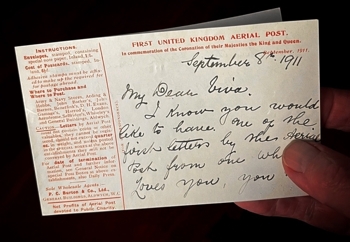

Several years would pass before aviation technology was capable of lifting more than a handful of wealthy passengers into the sky, but even before Tony Jannus’ historic flight, “aeroplanes” were seen as the perfect vehicles to carry the mail: on September 9, 1911, an “Aerial Post” service commenced between London and Windsor, in commemoration of the coronation of King George V.

That first scheduled airmail flight, flown in a Bleriot XI monoplane, was the stuff of headlines at the time, generating public excitement not unlike that that followed Lindbergh’s solo crossing of the Atlantic in 1927 and Neil Armstrong’s “…one small step…” onto the surface of the moon in 1969. If it seemed like the dawning of a new age, well, it was!

The airmail service ran for only four days, and the last flight was delayed for 10 days because of mechnical problems, bad weather, and a pilots’ strike. Only special pictorial post cards, envelopes, and stationery, purchased and posted from special boxes placed around London, could be sent. The excitement that Londoners felt is clear from the enclosure (shown at the right) that was in the cover shown above:

September 8th, 1911

My Dear Viva,

I know you would like to have one of the first letters [sent] by the new Aerial Post from one who Loves you much. Keep this, as it will be of great value in 20 years’ time, when I hope you and your Dear Mama will be happy & well & Jim Lord [will be] Mayor of London. I also hope you will be still at “Rowsley” as I think it is such a nice place & suits your health. With love from Your Grand Dad,

J. Pauley

J. Pauley wasn’t wrong. The few cents he spent for that airmail cover would steadily accrue value as a collectible; in 2023, examples were selling on-line from US$150 to more than US$1,000 for one that travelled on (by boat) from London to India.

War carries combat into the sky

In fewer than 30 years in the early 20th Century, pilots and their few passengers began to see continents, oceans, mountains, and deserts as portals rather than barriers to international travel and trade. The First World War, beginning in August, 1914, sparked a surge in new aviation technnology. Steel and aluminum came to be incorporated into aircraft design, giving airplanes greater resistance to stress and wear and making them safer; all-metal fighter planes soon followed. Large biplanes like the German Gotha bomber carried death and destruction to English cities. Oxygen stored in canisters allowed aviators to fly at previously unheard-of altitudes, and would assure airline passengers of the future that they could still breath even though they were tens of thousands of feet above the earth. Engines became more and more powerful, doubling the speed that pre-war aircraft could reach; streamlining reduced drag and gave aircraft even greater speed and range. And a German invented a way to synchronize a fighter plane’s machine gun so it would fire through a propeller without hitting it — bad news for Allied pilots, but meaningless for potential airline CEOs. By the end of the war, on November 11, 1918, airplanes bore little resemblance to the primitive aircraft of pre-war years.

Following the First World War, aviation technology really “took off”

In 1919, free of the restraints of the First World War, but benefitting from the wartime evolution of aviation technology,

• The U.S. Navy Curtiss seaplane NC-4 flew from the U.S. to Newfoundland, then to the Azores, on to Portugal, and finally landing in United Kingdom on May 31. It was the first crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by air.

• Two weeks later, on June 15, British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown completed the first non-stop transatlantic flight, flying a modified First World War Vickers Vimy bomber from Newfoundland to Ireland.

• Flying a modified Vickers Vimy bomber, pilot Ross Smith, his brother Keith Smith as co-pilot, and mechanics James Bennett and Wally Shiers became the first Australians to fly from Great Britain to Australia. Six entries started the race; the flight distance was estimated as 17,911 kilometres (11,123 mi) and total flying time was 135 hours 55 minutes. The Smith brothers and the two mechanicshe shared the prize money — US$723,541 in 2023 dollars — and the Smith brothers each received a knighthood for their exploit. The Vickers Vimy is now displayed at the Adelaide Airport.

Because of the speed of aircraft compared to any other mode of transportation, the use of air transport for long-distance continental and intercontinental mail routes soon became obvious, and fledgling airlines came to depend on lucrative government mail contracts instead of passengers, whose numbers were still too few to support the high cost of building, flying, and maintaining expensive, mechanically complex aircraft. In the 1920s, survey flights to explore possible mail routes connected the wealthiest, most technically advanced countries, notably Great Britain, France, Netherlands, and Japan with their various colonies, dependencies, protectorates, and commonwealths.

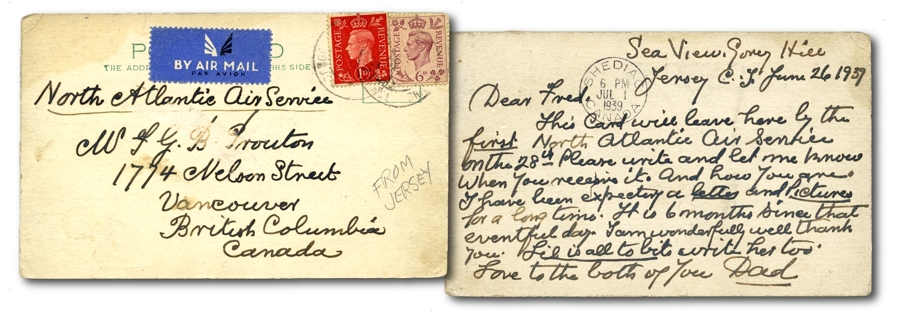

British, French, Dutch, Spanish, and American colonies with their exploring trans-continental and trans-ocean mail routes Gradually, as the speed, range, capacity, and comfort of airliners improved, potential passengers began to see them as reasonable alternatives to passenger liners. In the 1920s, passenger service was extended to Egypt, India, Singapore, and other parts of the British Empire in the 1920s and ’30s. Regular transpacific airmail service, from San Francisco to the Philippines (with several stops in between), began in 1935, and regular airmail service across the North Atlantic began in 1939.

Almost two decades would pass before people — wealthy people! — could enjoy truly fast trips, on heavier-than-air aircraft, across at least one ocean, the Pacific. Since November, 1935, the Pan American Airways System, popularly known as “Pan Am,” Pan Am had flown mail and freight Between North America and Asia. On April 28, 1937, Pan Am successfully completed its first scheduled transpacific crossing, carrying both mail and passengers in its Boeing 314 flying boat China Clipper.

Pan Am also made Transatlantic mail service available to Europeans and North Americans during this same period, but passenger service wouldn’t be available to them until July 29, 1939, when Pan Am made history again by completing its first scheduled passenger flight across the North Atlantic, flying both passengers and mail in the giant Boeing flying boat *Yankee Clipper” from its base at Port Washington on Long Island, New York, stopping for fuel at Shediac, New Brunswick; Botwood, Newfoundland, and Foynes, Ireland, and finally landing at Southampton, England. The return flight, two days later, followed the same route in reverse. On board was a postcard written by a resident of Jersey in the Channel Island.

On But Pan Am’s plans for frequent, scheduled flights across the North Atlantic were scuttled a month later, on September 1, 1939, when German troops invaded Poland, triggering the Second World War.

The coming of war was hardly a surprise. The world’s democracies, notably Great Britain and the United States, had been nervously observing events in Germany since 1933 when Adolf Hitler became the dictatorial German chancellor. In late June, 1939, a British woman, M. Garrett, wrote to a friend in the Lennox, Massachusets; the envelope was postmarked on June 30, and transported on the last “airmail only” Pan Am flight.

Ms. Garrett’s wrote to Miss Peters, Two days later, Great Britain declared war on Germany, and The British declared war on Germany went almost immediately to a war footing (although the Americans, pretending that neutrality would save them from Hitler and Nazism, would not declare war until the Empire of Japan attacked Pearl Harbor).

It’s not only the postmarks on Mrs. Garret’s envelope that tell the tale of the Pan Am flight. Mrs. Garret’s letter includes this statement:

I am mailing this via Yankee Clipper so I hope the Air Cover will be historical to you. Sorry I missed the 1st Air Mail when the Clipper went before, but this is the 2nd & represents the service started in 1939.x

I am hoping to see you in August or Sept. if the bombs don’t go off & if I can reconcile myself to leaving Alec. We don’t seem to live in as cheery a world as we once did & I am finding it hard to throw off a sense of fear.

Bullets and bombs target civil aviation

Two weeks and three days after she wrote to Miss Peters, on September 1, 1939, German forces launched a devastating naval attack on a military base at Westerplatte, near Danzig, and crossed the border into Poland. Great Britain, having vowed to defend Poland in case of just such an attack, declared war on Germany two days later, on September 3.

Only 10 hours after the British declaration of war against Germany, a German U-Boat, U-30, sank the British steamer SS Athenia. German bombs would not fall on England for a week, but the war brought a screeching halt to the growth of the civilian airline industry. Virtually all civil airliners and transports, including the Pan American’s already-famous flying boats, were immediately requisitioned by the military for the transportation of troops and war matériel. Mrs. Garret and Miss Peters would have been hard pressed to find any way to cross the Atlantic.

But the war also stimulated the development of new aviation technologies and, especially, the skills that pilots, navigators, and flight engineers would need to fly large aircraft long distances over uncharted oceans and continents and into distant theatres of war. Following the war, many of the surviving aircraft and air crews would be returned to civilian life where they would form the basis of a rapidly expanding airline industry.

Significantly, new technologies developed during the Second World War would help to transform the relatively primitive airliners of the 1930s into the powerful, fast, comfortable airliners that would create a “Golden Age of Flight,” assuming you were wealthy. One-way tickets for Yankee Clipper’s first passenger flight from London to New York had cost £272 (US$375) for the privilege of flying on the Yankee Clipper. These days, that seems like bargain for a transatlantic flight ticket, which in 2021 was running around USD$800. But bear in mind that $375 in 1939 could buy goods and services worth more than $3,000 in 2021. That’s approximately what you would pay today for a return ticket from Vancouver to Christchurch, New Zealand, a combined distance almost 750 times greater than the distance between St. Petersburg and Tampa.

-

Pilot Tony Jannus’s first flight across Tampa Bay on January 1, 1914 represented two “famous firsts”: The flight was the first to be flown by a federally-licensed airline pilot, and it was the world’s first flight by a scheduled commercial airline. But Jannus’s flying career would soon be cut short. On October 12, 1916, near Sevastopol (then part of Czarist Russia) Jannus’s plane, a Curtiss H-7 he was using to train Russian pilots, crashed into the Black Sea, killing him and his two-man Russian crew. His body was never recovered. He was just 25 years old. ↩︎