Letter from Castleknock — An Irish schoolboy writes home to his father (Part 1)

Part 1 | Part 2

This web page was revised and updated on November 5, 2015

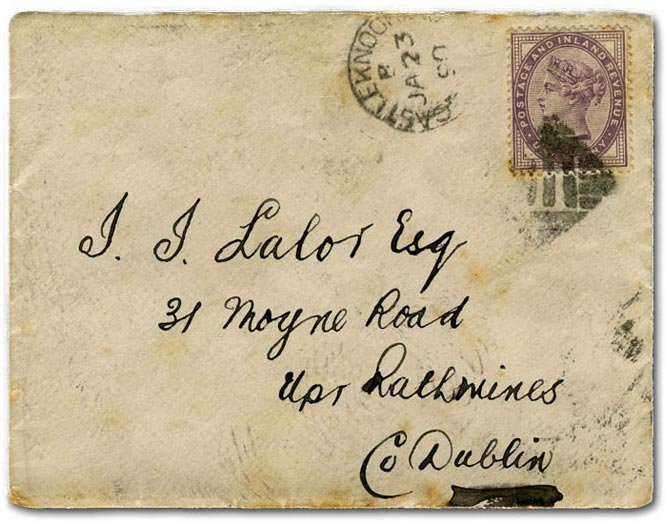

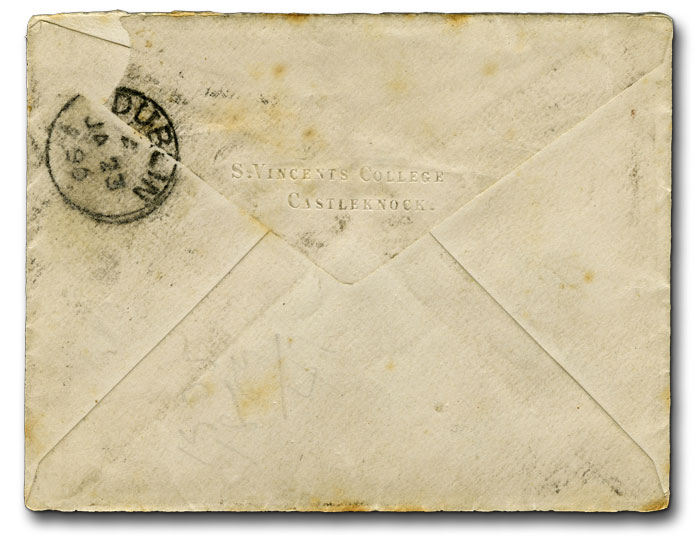

It is Thursday, January 22, 1890. Bernard Lalor, a new boarding student at St. Vincent’s College in Castleknock, a Dublin suburb, writes a letter to his father, J.J. Lalor Esq., using embossed St. Vincent’s stationery.

He addresses the small envelope to “31 Moyne Road, Upr Rathmines, Co. Dublin,” folds the letter twice, inserts it in the envelope (we postal historians refer to used envelopes as covers), seals the envelope, affixes a common, one-penny 1881 British stamp picturing Queen Victoria, and posts it. The cover is postmarked the next day, January 23.

19th Century mail

Bernard’s letter didn’t have far to go. His school, today known as St Vincent's Castleknock College (or Coláiste Chaisleán Cnucha in Gaelic) was and still is located about 8.5 km (5 miles) west-northwest of Dublin’s city centre. His letter’s destination, the Dublin suburb of Upper Rathmines, is 3.3 km (2.1 miles) south of Dublin.

In the 19th Century and well into the 20th, postal departments and their employees took pride in delivering mail promptly. Postal clerks at the “office of delivery” routinely postmarked the backs of covers upon receipt as a step in keeping records of transit times. Bernard’s cover was backstamped at Dublin General Post Office on January 23, 1890, the day after Bernard wrote his letter.

(An historical aside: The Dublin General Post Office became an iconic symbol of Irish Republicanism following the 1916 Easter Rising, the armed insurrection against British rule in Ireland. The post office, used as their headquarters by insurgents, was destroyed by fire six days after the beginning of the insurrection.)

Bernard’s letter was probably delivered January 23, the same day it was postmarked. By the the late 19th century, Londoners enjoyed between six and twelve mail deliveries a day; Dubliners almost certainly benefitted from at least two deliveries per day, and possibly more.

Such frequent mail delivery was probably a result of the need for efficient commercial communication, as well as the implementation of Greenwich Mean Time in 1847, which did away with local time keeping: Multiple, scheduled mail deliveries every day benefitted everyone; housewives could mail a penny postcard to order bread from a local baker or meat from a local butcher in the morning and expect delivery of their order in time for afternoon tea.

Not just old paper

Bernard’s letter to his father is not just old paper. It’s an artifact that sheds light on life as it was lived in Ireland the last decade of the 19th Century, a time when class structures and the British Empire itself were beginning to crumble, when large corporations were beginning to change the face of mercantilism, and the Industrial Revolution was imposing strict timetables and efficiency on society. Bernard’s letter also provides a glimpse into family life of the time, and the “public schools” of the day.

Bernard’s letter

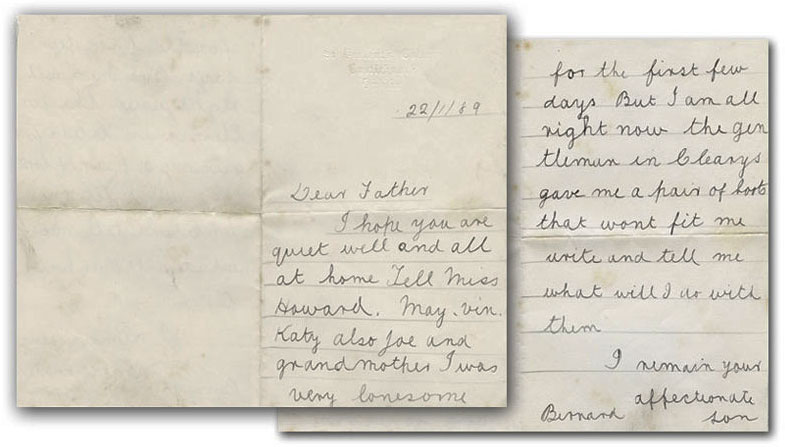

Bernard apparently had trouble keeping his lines of cursive handwriting straight and parallel: someone, presumably Bernard himself, inscribed not-quite parallel lines in pencil on the stationery before writing his letter.

Bernard’s legible handwriting reveals a homesick boy — probably a “new boy” at St. Vincent’s — putting the best face possible on a challenging period in his life.

An un-edited transcript of Bernard’s letter:

22/1/89

Dear Father I hope you are quiet well and all at home Tell Miss Howard. May, Vin, Katy also Joe and grandmother I was very lonesome for the first few days But I am all right now the gentleman in Clearys gave me a pair of boots that wont fit me write and tell me what will I do with them

I remain your affectionate son

Bernard

Bernard’s family

Census records from 1901, 10 years after Bernard posted his letter home, show that his family had moved to #23 Oak Terrace N.C.R. (North Circular Road) in Arran Quay, Dublin. The following persons are recorded as residents in his home:

James J. Lalor, Head of Family, age 54, married, a publisher.

Bernard refers to “May,” “Vin,” and “Katy,” undoubtedly his siblings:

Mary, age 20, a shop assistant

Vincent, age 19, a law clerk

Catherine, age 16, a student, or in the census desciption, a “scholar”

There is no “Joe” or Joseph Lalor listed in the 1901 census. Perhaps Joe was a brother who was living in 1890, but died before 1901.1 Or, he might have been a family friend. Nor is a grandmother listed in the 1901 census; perhaps she didn’t live with Bernard’s immediate family.

Catherine Howard —“Miss Howard” in Bernard’s letter — appears to have been the family’s housekeeper. She was 40 years old at the time of the census. A female servant, Catherine Dowling, 20, is also listed in the census.

Bernard addressed his letter to “J.J. Lalor, Esq”. Esquire formerly was a courtesy title used in the United Kingdom for certain members of the gentry, but later came to be used as a general courtesy title for any man in a formal context, usually appended to his name as in "John Smith, Esq." Clearly, Bernard’s family was part of the new and upwardly mobile merchant class. It can’t have been inexpensive to send a boy to St. Vincent’s Castleknock College, nor to buy him boots at Clerys. So, who was J.J. Lalor?

The Lalor surname is common in Dublin today, and a brief internet search returns the information that J. J. Lalor Ltd., one of Ireland's oldest printing firms, was established in 1883 by James Joseph Lalor, operating from premises in Dublin's North Earl Street. It seems unlikely that he was not than Bernard’s father. And there is this: the 1901 census lists Bernard’s occupation as “printer”. It takes no imagination at all to assume the Bernard began working at his father’s printshop when his formal education came to an end.

According to the J.J. Lalor web site, a son named Larry operated the business in partnership with Vincent and Catherine in the 1920s through 1949, when Catherine purchased it from her brothers. Available census records for the years following 1911 do not provide individuals’ names.

The “Public School” experience

St. Vincent’s College was and still is a “public school,” which in the United Kingdom has traditionally meant, ironically, that it’s a private school. Like other public schools in the United Kingdom at that time, St. Vincent’s catered mostly to the sons of upper- and upper-middle classes between the ages of 13 and 18.

The system seems to have succeeded in reaching its stated goals of “…combining moral and literary instruction,” with school boards having the responsibility of determining the form and content of religious instruction. No pupils were required to attend classes in religion if their parents did not approve of such instruction. Most schools in Ireland in Bernard’s time (and even now) are operated by either Roman Catholic or Protestant organizations.2

Many prominent leaders emerged from the U.K.’s public schools, and St. Vincent’s was no exception: among its graduates have been actor Colin Ferrel, Air Chief Marshal Sir William MacDonald, and archbishops of New Zealand and Toronto; the first president of the Republic of Ireland, Éamon de Valera, taught at St. Vincent’s.

Nevertheless, novelists, playwrights, biographers, and film makers have long focussed on the complex mix of homesickness, bullying, friendship, academia, and sexuality that public school boys were expected to thrive in. Novelist Evelyn Waugh observed in his 1928 novel, Decline and Fall, that “…anyone who has been to an English public school will always feel comparatively at home in prison.” Psychologists know that long-term harm can result from the practice of separating young children from their families.

Was St. Vincent’s like a prison to Bernard? Possibly. He may have been especially vulnerable to the stresses of public-school life: his letter, addressed to his father, makes no mention of a mother. At home, Bernard appears to have been surrounded by close family members and perhaps friends, both male and female.

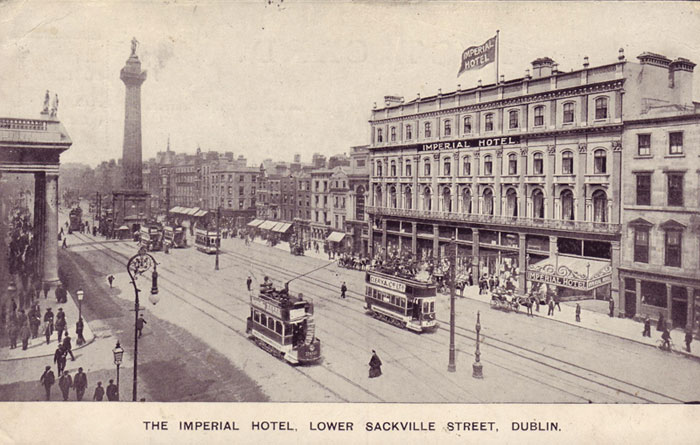

A pair of ill-fitting boots from “Clearys”

In his letter from St. Vincent’s college, Bernard mentions buying ill-fitting boots at “Clearys,” which is almost certainly a misspelled reference to Clerys, the famous department store on Upper O'Connell Street in Dublin, directly across the street from the General Post Office. Clerys opened in 1853 as the “Palatial Mart” or “New Mart,” a large, sumptuously ornamented Victorian department or “monster” store. The economic downturn of the late 19th Century forced the owners to sell; M.J. Clery bought it and changed the name to Clery’s in 1883. It is still in business today, at the same location, although, like the General Post Office, the building was destroyed in the Easter Uprising of 1922.

Questions remain

Finally, we are left to ponder these questions, the first rather more serious than the latter: What accounts for his mother’s absence from the Lalor home in 1901, and her apparent death at some point within the next 10 years? And, was Bernard able to return to Clerys department store to exchange his ill-fitting boots for a more comfortable pair?

Part 1 | Part 2

-

Dublin was not a healthy place to live in 1900. The average annual death-rate in Ireland was 17.3 persons per thousand; in Dublin it was 24.8. Infant mortality largely accounted for this high death-rate: In 1901 an average of 168 babies died per 1000 births. The average for the rest of Ireland was 101 per 1000 births. It was a rare family that hadn’t lost a child; although death rates among Irish poor were higher, middle class families like Bernard Lalor’s were hardly immune to early death, often from tuberculosis. ↩︎

-

Source: Spartacus-educational.com ↩︎