Marching to War — France, Great Britain, and the United States face Ho Chi Minh’s guerilla army

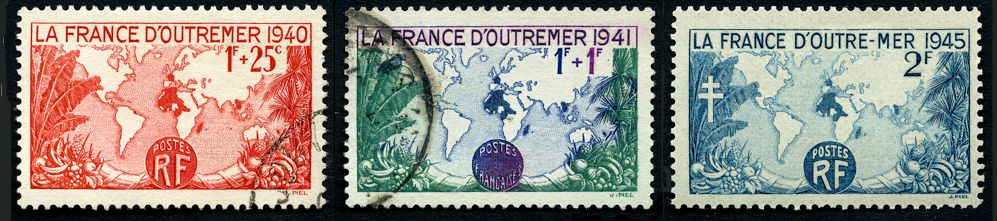

On April 15, 1940, France issued a semi-postal postage stamp picturing a map of the world and its colonial possessions, which stretched from the Caribbean and South America to Africa, India, and Southeast Asia. Two more stamp of a similar design would be issued, one in 1941, after France had been occupied by Germany, and the last in 1945, after VE Day.

A stamp of a similar design, supposedly for the benefit of French seamen, was issued in 1941; in 1945, France issued yet another similar stamp, for regular postage. The 1f+25c stamp, was issued i.

The 25-centime surcharge of the 1940 was to be used for the benefit war charities; the 1f surcharge of the 1941 stamp was to benefit French sailors.

The real purpose for all three stamps was almost certainly to support and justify French claims of sovereignty over French colonies in France d'outre-mer — Overseas France.

Mission Civilisatrice

In the early days of the Second World War, France was desperate to hang onto is colonies in the Caribbean, South America, Africa, India, and Southeast Asia. The stamps were visible propagandistic symbols of the mission civilisatrice, French for "civilizing mission” and the underlying principle of French colonial rule in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

France was certainly not alone. The European colonial powers felt it was their duty to bring Western civilization to what they perceived as backward peoples. Rather than merely govern colonial peoples, the Europeans would attempt to Westernize them in accordance with a colonial ideology known as "assimilation".

In April, 1941, following the establishment of the Vichy collaborationist government in southern France, the 1f+1f stamp was issued to benefit Vichy French seamen. (The Vichy government was allowed to administer southern France as well as French colonies abroad which had not opted to join Free France, the collective of French colonies formed by Charles de Gaulle following the German occupation of France.)

In September, 1940 Japanese forces occupied French Indochina, but allowed the Vichy French administration to continue. In March, 1945, the Japanese revoked French power in Cochinchina, Annam, and Tonkin (the three regions of French Indochina that we know as the modern state of Vietnam), and created a puppet state. Vichy French administrators in French Indochina were jailed, and Indochina ceased, temporarily, to be a French colony.

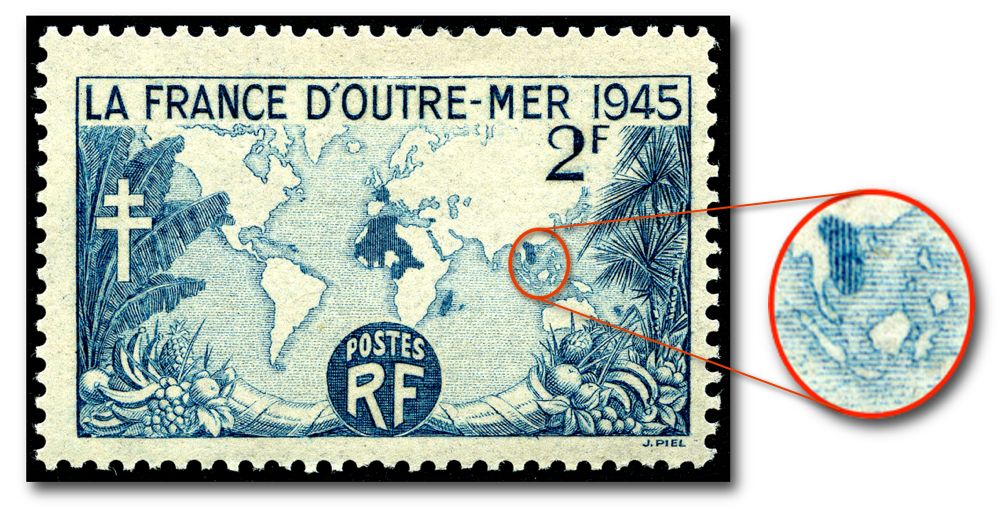

On September 17,1945, soon after the liberation of France, France issued the 2f stamp shown below; the image points out the location of Indochina.

The 1945 stamp was no doubt issued to impress on the French people and the world that French colonialism was alive and well, although it was not — the war had taken its toll. In Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh forces were challenging British Indian troops who had been sent to Indochina to take over control from the Japanese and to release French POWs. Without help from the British and the Americans, it was unlikely that Indochina could avoid a takeover by the Viet Minh. It's an interesting irony of history that the British officer in charge of the mission to neutralize the Viet Minh actually released Japanese POWs to fight against alongside French and British soldiers. In another irony, many Japanese soldiers who found themselves stranded in Vietnam after the Second World War joined the Viet Minh! Here is a postcard sent during the war by a Japanese soldier in Vietnam to his father in Japan:

With the death of Franklin Roosevelt, who supported the nationalistic aspirations of colonized peoples around the world, the United States moved to support French colonial claims. U.S. support was mostly clandestine; President Truman and his most senior civil and military advisors did not wish to be seen as apologists for European colonialism, but felt that they needed to support both France and Great Britain, neither of which relished losing their colonies, and both of which could assist the U.S. in resisting the spread of Soviet communism. To that end, the United States transported French soldiers to Indochina after the war, and supplied them with American weapons and materiel, including such mundane but important items as helmets, boots, and canteens, not that such American largesse did them any good.

In 1954, the French army moved into the remote valley of Dien Bien Phu in North Vietnam. Their plan was to use the valley as the site for a forward base, from which they could interdict the movement of communist supplies from neighbouring Laos into North Vietnam. The Viet Minh had other ideas: in one of the most remarkable military maneuvers in history, they moved heavy artillery up steep mountainsides to positions from which they could bombard French positions below. In tactical terms, the Viet Minh position was brilliant: they could fire with impunity on French targets, yet French guns could not be aimed high enough to hit the Viet Minh. In fact, the French gunners could not even see the Viet Minh guns, which were sited on the reverse slopes of the mountains. Here is a postcard showing the Valley at Dien Bien Phu:

/upload/2000627904.jpg

Over the next several weeks, the Viet Minh pounded the French with with artillery and anti-aircraft fire, and eventually overran the French positions. This is a stamp issued by North Vietnam in 1954, commemorating the victory at Dien Bien Phu:

/upload/2000627877.jpg

None of us knew at the time, even if we knew that the Battle of Dien Bien Phu was in progress, that American and French politicians seriously discussed using nuclear weapons in support of the French. The idea was scuttled because of the danger to the French Army. Apparently the potential damage to civilization was not considered. The United States remains the only nation that has actually used nuclear bombs against enemies.

Both the French and the Americans would have been wise to heed Ho Chi Minh. Soon after the Second World War ended, Ho spoke with French politicians before the First Indochina War started, in December, 1946:

If we have to fight, we will fight. You will kill ten of us, and we will kill one of you, and in the end it you who will be exhausted.

A common misperception of both French and American soldiers in Vietnam was that communist soldiers were sickly, poorly trained, poorly armed, and little more than slaves to their Communist masters. In truth, they were tough and very dedicated, and able to fight on little food. American soldiers and marines are not wimps by any means, but we were not inspired by nationalistic ideals — our overarching goal was simply to survive. Here is my photograph of a Viet Cong soldier, captured by my battalion in 1966. He had thick callouses on his shoulders and feet; it was clear that he had probably walked the Ho Chi Minh Trail all the way from North Vietnam:

Ho was wrong. Sort of. In the First Indochina War, 1946 - 1954, communist casualties were “only” two or three times greater than French casualties, but the French were exhausted and soon after the Battle of Dien Bien Phu they quit Vietnam for good. In the “American Vietnam War,” 1955 - 1975, about one million North Vietnamese and Viet Cong soldiers died, compared to 58,000 Americans, a 20:1 ratio. But Americans, no less exhausted than the French had been, gave up in 1975, and communist forces soon overran all of South Vietnam.

Bob