Russian MiG-15 fighters redefined aerial combat

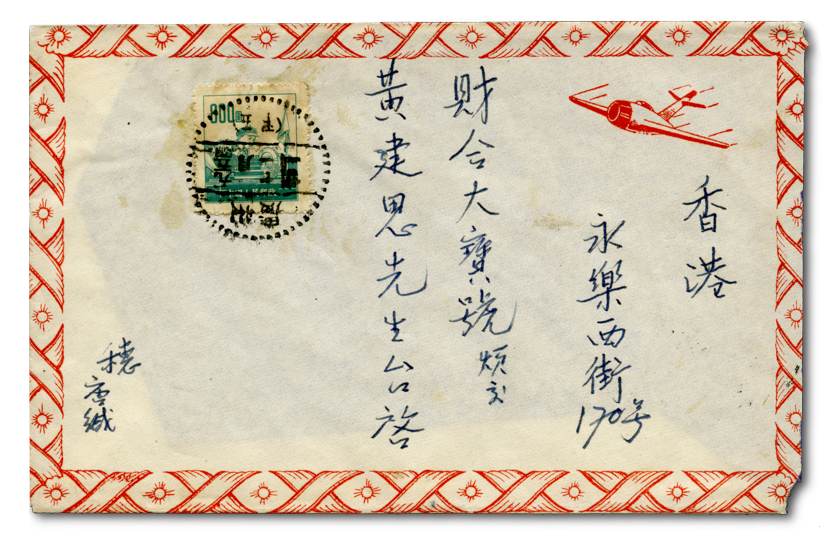

In the early 1950s, high in the skies over the Korean peninsula, a new kind of aerial battle was joined. The pilots of Russian MiG-15s and American F-86 Sabres, hurling their swept-wing jet fighters toward each other at transonic speeds1 and sometimes beyond, gave new meaning to the word "dogfight." A domestic cover2 in my collection, posted from Canton to Hong Kong in 1954, recalls those first, tentative steps into the age of jet combat.

The aircraft drawing on the cover represents a Russian MiG-15, designated the "Fagot" by NATO; the name "MiG" comes from the first letters of the surnames of its two Russian designers, Artem Mikoyan and Mikhail Gurevich, separated by the Russian word for “and” — и in Cyrillic, i in English.

When the Korean war started in 1950, I was only eight years old but old enough to understand that momentous events were occurring a long way away from my home in the tiny village of Arenas Valley, New Mexico. The war came to me largely through newsreels at the Saturday movies at the Gila Theatre in nearby Silver City. I was thrilled by the black-and-white scenes of aerial combat between North Korean MiGs and U.S. Air Force F-86 Sabre, commonly known simply as the “Sabrejet”. The newsreels were highly sanitized — even bloodless — and patriotic; I was far too young to appreciate the broader implications of aerial combat, or even war itself. It was exciting and I wanted to be a Sabrejet pilot!

The MiG-15’s German & British roots

German wartime aerodynamic research, British jet-engine technology, and Soviet design ingenuity came together in the design and production of the MiG-15.

When Allied forces fought their way into Germany in 1945, their goals were two-fold:

• Germany’s unconditional surrender.

• The capture of German military hardware and German scientists and engineers who had developed such weapons as the ME-262, the world’s first operational jet fighter, and the “Vengeance” weapons which had wreaked havoc in Western Europe and England — the V-1 “Buzz Bomb” and the V-2 ballistic missile.

Both the Soviets and the Americans made off with the technology and personnel that would launch both nations into the Cold War, armed with new, German-inspired weapons, and into the Space Age. The Russians, specifically, developed the MiG-15’s airframe from German developments in high-speed jet flight, but they were missing one vital component — a jet engine capable of powering the MiG-15 airframe. But the British came to the rescue.

In 1946, desperate for foreign currency and ignoring American disapproval, the British government allowed Rolls-Royce to export 40 new Nene jet engines, a Second World War development which first saw use in the U.K.’s Hawker Sea Hawk and Supermarine Attacker. The Soviets promptly copied the design, began to produce near-identical engine called the Klimov VK-1, and installed it in the MiG-15.

The same engine was produced under license in China, along with the MiG-15 itself, although China only made the two-seat trainer version of the MiG, called the JJ-2, for Jianjiji Jiaolianji-2 — Fighter Trainer-2.

The MiG-15 first saw combat at the end of the Chinese Civil War. On April 28, 1950, a MiG-15 flown by a Soviet pilot downed a Nationalist Chinese P-38 Lightning. With the outbreak of the Korean War in June of the same year, the North Koreans began operations flying a variety of piston-engine fighters. These were soon swept from the sky by American jets and B-29 formations began a systematic aerial campaign against the North Koreans. With the Chinese entry into the conflict, the MiG-15 began to appear in the skies over Korea. Quickly proving superior to straight-wing American jets such as the Lockheed F-80 Shooting Star and Republic F-84 Thunderjet, the MiG-15 temporarily gave the Chinese the advantage in the air. (One of the ironies of the air war in Korea is that early American victims of the MiG-15 were F4F Panther jet fighters, powered by none other than the Nene jet engine, built under licence as the Pratt & Whitney J42.)

MiG Alley

The MiG-15's arrival compelled the US Air Force to begin deploying the new F-86 Sabre to Korea. Arriving on the scene, the Sabre restored balance to the air war, but still faced the MiG’s formidable opposition.

In MiG Alley,3 Sabres faced flights of as many as 70 MiGs flying at their higher operational ceiling of 50,000 ft or more. The MiG could outclimb the Sabre, had tighter turning characteristics (except at high speeds), and greater dive acceleration, but poor control at high speeds and some instability at high altitudes.

Although the F-86 could fly right up to and sometimes briefly beyond the speed of sound, and the MiG-15 was almost supersonic, they fought at relatively sedate speeds with Second World War machine guns, cannon, and rockets. The MiG's two 23mm and one 37mm cannons were more effective than the Sabre's six .50 calibre machine guns, but American and Canadian pilots with superior training had the benefit of the outstanding, gyroscopically stabilized K14 gunsight which computed the necessary deflections required to ensure a hit on the target.

The MiG-15’s Chinese and Russian pilots — no Koreans flew the MiGs — could usually dictate when the fight began, but the Sabres usually won the victory. By war's end, American F-86 Sabre pilots, in dogfights reminiscent of those of the Second World War, had claimed 792 victories over MiGs. Did the Americans really shoot down that many MiGs? Perhaps not.

Historically, fighter pilots have exaggerated their victories. During the Battle of Britain, Allied pilots claimed to have downed more German aircraft than the German airforce had! However, it would be unfair to say that any of the pilots were lying: their "field of combat," even as early as the First World War, was airspace measured in cubic miles. In Korea, at times nearing the speed of sound, pilots were fortunate even to see an enemy aircraft, much less close with it. Unless an enemy aircraft came apart in mid-air or exploded, pilots could not always be certain that their targets had been hit, or that an obviously damaged enemy aircraft was necessarily a doomed aircraft. There is, however, no question that the MiG pilots were outclassed: Only 78 Sabres were lost; the majority of their surviving pilots became POW’s.

MiGs on stamps

As many as 18,000 MIG-15s may have been manufactured making it the most widely produced jet fighter in the world during the early 1950s. It was used by the air forces of all Eastern Bloc nations, and by such Russian allies as Egypt. Some are still flown in air shows around the world. It’s not surprising that postage stamps reflect the aircraft’s popularity and effectiveness.

The MiG-15 fighter came into my life again not long after I had started my first hobby, stamp collecting. Among my early purchases of stamps, which probably came on approval from the H.E. Harris stamp company, was a set of Hungarian airmail stamps that had been issued in 1954, and included a pictorial stamp showing two Hungarian Air Force MiG-15s flying in formation.

Obtaining a translation of the names and addresses of the cover’s sender and recipient has proved to elusive, even for Chinese speakers. Seven people have provided what they believed to be correct translations. However, because of differences between Cantonese and Mandarin, their translations were not always in agreement.

My most recent correspondent wrote in an email,

The transcription of the proper names will depend on whether you are transcribing from Mandarin or Cantonese (the written language of the various dialects is basically the same, in that time frame, traditional script; but the words are pronounced differently in the various dialects).

He said that a translation in Cantonese indicates that the cover was posted by Mr. Kin Sze (or See) Wong. In Mandarin, he would be Mr. Jiansi Huang (using current Mainland Chinese Mandarin. A Mandarin transcription into English at the time of mailing, in 1954, would give the name of Mr. Chien-Si Huang.

Given the sender’s and receiver’s addresses, it would be more proper to describe the letter in Cantonese transcription for historical accuracy — hence, Mr Kin Sze Wong …. I am not a Cantonese speaker, so I am going with Sze instead of See, but I can see where both might be used.

It was mailed by a person named Tong from Guangzhou (formerly Canton) to Hong Kong, in 1954. Three of my translators say that it was addressed to a Mr. Wong Kin Sze or See. Only one translator says his name is Jian En Wang; another, commenting on this translation, says that this pronunciation is not possible in either Cantonese or Mandarin, and insists that in Mandarin the name is "Huang Jian Si".

The stamp franking the letter was issued without gum, hence the staining from manually applied glue. Mr. Wong Kin Sze/Huang Jian Si worked at or owned a shop called "Choi Hap Company" at "No. 170, Wing Lok Street West," in the old, colonial part of Hong Kong. The name of the company includes a character which means "big," apparently used as an honorific; the street name can be translated as "Always Happy Street."

At the bottom of the address is the notation "NG PING," probably the name of a local post office. The date of postmark date is unclear; it may be November 11.

Mr. Wong Kin Sze/Huang Jian Si worked at or owned a shop called "Choi Hap Company" at "No. 170, Wing Lok Street West," in the old, colonial part of Hong Kong. The name of the company includes a character which means "big," apparently used as an honorific; the street name can be translated as "Always Happy Street."

At the bottom of the address is the notation "NG PING," probably the name of a local post office. The date of postmark date is unclear; it may be November 11.

If nothing else, this cover illustrates the gulf in communication that can exist between speakers of different languages. One wonders how the Chinese themselves manage to communicate in writing! Since I can scarcely order fried rice in a Chinese restaurant, I will leave it to the linguists to work out their disagreements.

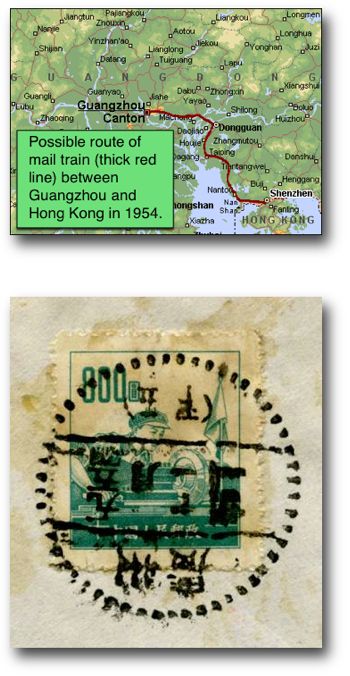

Guangzhou is about 125 km (78 miles) west-northwest of Hong Kong. The cover has a vague "airmail" appearance, but in the mid-1950s all passengers, parcels and mails travelled by train from Guangzhou to Hong Kong.

The price of the stamp — 800 yuans, or the equivalent of eight fens today — was the correct amount for surface letters weighing less than 20 grams (.7 ounce).

The yellow-orange smears on and around the stamp are easily explained: Until 1960, stamps of the People's Republic of China were issued without gum, and had to be affixed with glue; the person who posted this letter went to the glue pot before going to the letter box. The stamp shows a female lathe operator. (The cancellation is upside down in relation to the stamp; if you read Chinese, see the same image, inverted.)

In 1954, when my Chinese cover was sent through the mails, the MiG-15 had largely played its part in history. The advanced MiG-17 was already flying; in the late 1960s, it would threaten a new generation of American fighter pilots in Viet Nam.

-

Transonic speed refers to speeds near that of sound in air or about 741 mph (1185 kph) at sea level and especially to speeds slightly below the speed of sound at which the speed of airflow varies from subsonic to supersonic at different points along the surface of a body in motion relative to the surrounding air. ↩︎

-

Many philatelists collect not only stamps but also “covers” — used envelopes that have gone through the mail stream. Another term for covers is, confusingly, “postal history,” which also refers to the study of mail routes, rates, and regulations. It’s useful to think of old envelopes as postal artifacts: addresses, return addresses, stamps, cancellations and other postal markings, hand-written notations, labels, censor tapes, and illustrated cachets all serve to reveal the provenance of covers. ↩︎

-

MiG Alley is the name given by United Nations (UN) pilots to the northwestern portion of North Korea, where the Yalu River empties into the Yellow Sea. During the Korean War, it was the site of numerous dogfights between UN fighter pilots and their opponents from North Korea (including some unofficially crewed by Soviet airmen) and the People's Republic of China. ↩︎