Monochrome Photographs by Bob Ingraham

Introduction

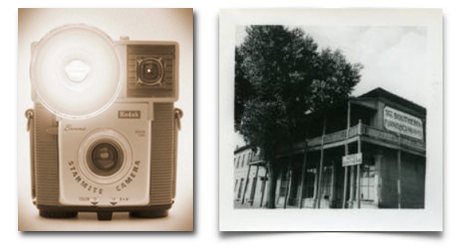

In the summer of 1960, when I was 17 and ready to begin my senior year at Western High School in Silver City, New Mexico, I bought a Kodak Starmite camera. The first photograph I took was of the Old Southern Hotel, a local landmark with an historical connection to the notorious outlaw, Billy the Kid. Billy’s mother, Mary McCarty-Antrim, was a laundress at the hotel.

I had learned the basic steps in developing film and making enlargements from my father, who had been a newspaper reporter and photographer back in the late 1940s when we lived in New York State. Soon I had set up a makeshift darkroom in a brick shed in my family’s back yard. The shed was built in the same year as the house, 1912; light shone through holes in the walls where mortar had fallen out. It had no plumbing, so I had to carry water from the house to the shed so I could mix developer and fixer. I think I used my dad’s old enlarger, but I might have borrowed one from a friend.

Mr. Steele, the teacher in charge of the El Potranco (The Colt), our school yearbook, knew nothing about photography, so he hired me to be his photographer. He turned the school’s 4X5 Speed Graphic over to me and put me in charge of the darkroom, located in an elementary school near my home. In that year, mostly by experiment and reading books and photography magazines, I began learning about shutter speeds and f-stops and depth of field and film “speed” and flash synchronization. And I learned that having that big camera resting on my shoulder was a free pass into basketball and football games!

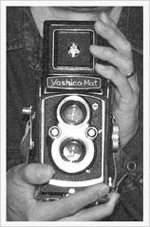

In 1961, I graduated from high school, started taking courses at Western New Mexico College, purchased a new Yashica-Mat twin-lens reflex camera (a semi-professional Japanese camera based on the classic German Rollieflex), began to take photographs for the Silver City Daily Press, and was hired by the El Paso Times as a stringer.

On May 2, 1962, a Wednesday, my job with the Times nearly nearly killed me. Literally. I was writing a story (and taking pictures) about forest-fire fighting in the nearby Gila National Forest. I hitched a ride on a Beech T-34 Tutor “bird dog” plane, used to locate fires and guide air tankers to their targets. That was a mistake: near a small fire, at very low altitude, the T-34 apparent wind shear flipped it upside down and smashed it into the forest. Both the pilot and I survived; my injuries were relatively minor, and the pilot’s were severe, but my Yashicamat was destroyed.

Events moved quickly after that plane crash. Insurance paid for my busted camera; I finished writing my forest-fire article, bought a 35mm Nikon SP rangefinder camera, and in September enrolled for more college courses, including American History, which I had flunked in my freshman year. But

I became a hospital corpsman. After a two-year tour of duty at the Navy hospital in Yokosuka, Japan, I was seconded to the U.S. Marine Corps and ended up in a rifle company in South Vietnam. On March 5, 1966, my platoon was ambushed by Viet Cong and North Vietnamese troops. Within a few minutes, I was seriously wounded when a bullet smashed my right femur. I was lucky. Ten Marines in my company were killed.

I was evacuated to the U.S. and hospitalized for the next 10 months at the U.S. Naval Hospital in San Diego. The next few decades were taken up by marriage, university, fatherhood, and jobs in journalism, education, and photography. I retired in 2000, and now live in Vancouver.

Over my lifetime I’ve used several different cameras. In addition to the Kodak Starmite, the Speed Graphic, the Yashica-Mat (which I had repaired in Japan), and the Nikon SP, I’ve owned the following cameras:

• Nikon F, including the Photomic light meter and several lenses • Nikonos I (Nikon’s first waterproof camera, which I took with me to South Vietnam) • Mamiya C33 TLR • Pentax 645 SLR • 4X5 Crown Graphic • Bronica 6X7 SLR • 4X5 pinhole camera, made by Pinhole Resource v• Canon PowerShot G2 digital camera • Canon EOS Rebel T6i digital camera • iPhone 6 camera

I tried other cameras along the way, including a used Leica IIIg, which had a hole in the shutter curtain, and a Nikon S; a Rollei 35mm camera which was fun to use, when it worked, and an automatic Pentax SLR (a truly horrible camera). Once I played around with a Brownie box camera from the 1930s. It was fun! Old cameras like that Brownie add an element of the unknown to photography. Their viewfinders are sometimes was so bad that you can’t be certain that you’re composing the photograph well, or even aiming the camera in the right direction. A complete lack of exposure control means that over- or under-exposure is likely. If you forget to advance the film, you’ll take an inadvertent double exposure in just a click. And you won’t have a clue about how your photographs look until you get the film developed and printed.

One valuable lesson I’ve learned over my several decades of photography is that the photographer is far more important than his or her camera. I have taken terrible photographs with expensive cameras and wonderful photographs with dirt-cheap cameras. I’ve learned that many photographic opportunities present themselves just once in a lifetime: Every photographic subject appears once and once only in any given circumstance of light and shadow, tonality, and contrast: Sky and clouds, skaters and babies, leaves and waves, change minute by minute — never will you see the same clouds and sky again, not if you live to be as old as Methuselah. Skaters and dancers and

Although this portfolio showcases black-and-white photographs, I have taken many colour photographs, and I appreciate them. Nevertheless, my favourite subjects generally demand the use of black-and-white imagery, at least as far as I’m concerned. Black-and-white photographs aren’t really black-and-white, but are monochrome images consisting of a range of tones that in my version of a perfect world range from black to white, and as many tones of grey that the photographer can achieve.

I’ve heard people say that monochrome photographs are boring, not real, old fashioned. They complain that they aren’t coloured! Well, yes, that’s true. However…

I was born in 1943, and grew up listening to radio dramas. When I was in my early teens, my favourite radio program was Gunsmoke. Gunsmoke portrayed the realistic daily life of a U.S. Marshall, played by William Conrad, as he tried to keep the peace in Kansas Territory in the late 19th Century. To this day I can hear his gravelly, resonant voice:

Around Dodge City and in the territory on west — there's just one way to handle the killers and the spoilers — and that's with a U.S. Marshall and the smell of Gunsmoke!

The “Radio Gunsmoke” ran for nine years, from 1952 until 1961; in 1955, CBS Television began broadcasting a “made for TV” version which lasted until 1975. I’m sure I heard nearly all of the radio programs, and probably saw a majority of the TV programs, but it’s one of the scenes from the radio programs that I recall most vividly: In that scene, Marshall Dillon is hoping to arrest one of those killers or spoilers, who is trying to shoot Marshall Dillon from the cover of some large boulders, probably with a rifle. Marshall Dillon, armed only with his revolver, is running from boulder to boulder, trying to get closer to the bad guy so he can arrest him — Marshall Dillon always prefers to arrest the “killers and the spoilers” rather than kill them. To this day I can easily recall Marshall Dillon’s laboured breathing and pounding footsteps as he dashes from boulder to boulder, bullets just missing him and ricocheting away — KUH-Zhingggggggg! — and then hearing nothing at all except Marshall Dillon’s heavy breathing. I had plenty of time to build a clear and detailed image in my mind of what was happening, and what might happen. It was tense!

A few years later, the same plot appeared in the TV Gunsmoke series. It wasn’t nearly as exciting as the radio version. I didn’t need to use my imagination to see the hillside, the boulders, the dust where bullets were ricocheting off boulders, the clear blue sky, Marshall Dillon running and jinking and feinting and breathing hard as he avoided being shot and moving closer and closer to the bad guy. I enjoyed the TV version of that program, but I didn’t need to use my imagination or even think as I watched it. Television programs essentially pour all of the information you need or at least want to have straight into your eyes and ears. There’s little need to interpret what you see and hear. Imagination is not needed. Even if you try to imagine more detail and information into existence, the TV images and sounds snatch your attention from your thoughts back to the TV. Your brain is held captive. Listening to a radio drama is completely different: Because you aren’t provided with any visual information, you have to build the set in your brain, complete with colour, and light, and shadow. You even have to create subtle facial expressions in your mind’s eye to match the voices you are hearing.

In reality, it’s difficult to make a photograph that doesn’t have some colour in it. Photographic paper may not be perfectly white; some photographic papers are made with subtle tonality. Classic papers, few of which are made these days, often were ivory toned. One of the pleasures of creating one’s own monochrome photographs, even in this digital age, is to tint monochrome photos with subtle colour. My portfolio includes photographs toned with selenium, which creates a subtle purplish tone, or various intensities of sepia toning.