The Azure Mining Company posts a letter

From Silver City, New Mexico to Mexico City

A cover (a.k.a. “dirty old envelope”) posted in 1895 by the Azure Mining Company, operating near Silver City, New Mexico, is philatelic gold to me: I grew up in Silver City, and I have always been interested in the history of the area, especially its mining history.

As its name implies, Silver City, located in the southwest corner of New Mexico, was a centre of silver production, as well as gold, zinc, and lead. It so well known, in fact, that a Dutch atlas — the Schoolatlas, published in 1898, shows only two communities in New Mexico, the capitol, Santa Fe, and Silver City. But Silver City was also well known for its high-quality turquoise, and the most famous turquoise mine of all was the Azure Mine, located 10 miles southwest of Silver City, in the Burro Mountains.

In 1885, the governor of what was then the Territory of New Mexico, mentioned the mine in his annual report to the federal government.

The Azure mine was located in Azure, New Mexico, 10 miles southwest of Silver City, New Mexico. There may or may not have been a small community, named Azure, that grew up around the mine. According to a list compiled by Carl W. Scholl of Silver City, titled “Towns, Camps, Railroad stops and Post Offices that have existed in Grant County, NM”, Azure had a post office that operated for an exceptionally brief period in 1895, from January 7 to April 27. According to the New Mexico Territorial Postmark Catalog by Thomas K. Todsen, no postmarks are known from Azure. The brief life of the Azure post office, assuming there actually was an Azure post office, may explain why the Azure Mining Co. cover was mailed in Silver City rather than Azure; it’s more likely that the company’s office was in Silver City.

The Azure Mining Company cover is a type known as a stamped envelope, pre-printed with an embossed stamp, with the white embossed portion above the coloured portion. Such envelopes, sold only in post offices, are also called Postal Stationery Envelopes, or PSEs.

The Scott Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps lists 11 varieties of this particular envelope, #U294-U304, based on different colours of ink (blue and dark blue) and different colours of paper (white, amber, manila, amber manila, oriental buff, and blue). The ravages of age make it difficult to determine the original colour of the envelope; my best guess it’s the variety on amber paper.

The envelopes were produced from 1887 through 1894 by three different companies: Plimpton Manufacturing Co. and Morgan Envelope Co. of Hartford, Conn., and James Purcell, Holyoke, Mass. They were replaced in 1899 by Scott #U352.

The cover is upfranked (collector talk for added postage) with Scott #222, the attractive four-cent dark-brown stamp from the 1890-93 definitive issue, picturing President Abraham Lincoln. The stamp is one of a set of eleven face-different stamps.

Five cents total postage was more than double the amount that was required, unless the letter was overweight: From April 1, 1879, through June 30, 1887 the US letter rate to Mexico had been five cents per 1/2 ounce. On July 1, 1887 it was lowered to two cents per ounce to match the US domestic letter rate. It’s possible that the sender (or the post office) might not have had a one-cent stamp available.

The Lincoln stamp is tied1 to the cover with a Silver City CDS cancellation.2 The date is unclear, but based on the evidence provided by backstamps, it is probably February 15, 1895. A segmented cork cancel effectively “kills” the Lincoln stamp and also ties it to the cover, and was also used to cancel the embossed stamp.3

The handwritten address on the cover is unclear. The name of the addressee seems to be “E. Rolland”. In the absence of an enclosure, is it unclear why the someone at the Azure Mining Company was writing to Señor “Rolland”.

An illegible word — library? — appears above “Ciudad de Mexico”. Its significance is not known.

In 1895, Silver City was connected to the rest of the world by the Atcheson, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, often and simply called the “AT & SF”. The cover was probably transported by train from Silver City to El Paso, Texas via the southern New Mexico communities of Deming and Rincon. From El Paso, it would have been carried across the Rio Grande River to El Paso del Norte (The Pass to the North, present-day Ciudad Juárez, known much more commonly as simply Juarez). From El Paso del Norte, it would have continued its journey to Ciudad de Mexico (Mexico City) on the Ferrocarril Central Mexicano (Mexican Central Railway), which was owned by the AT&SF.

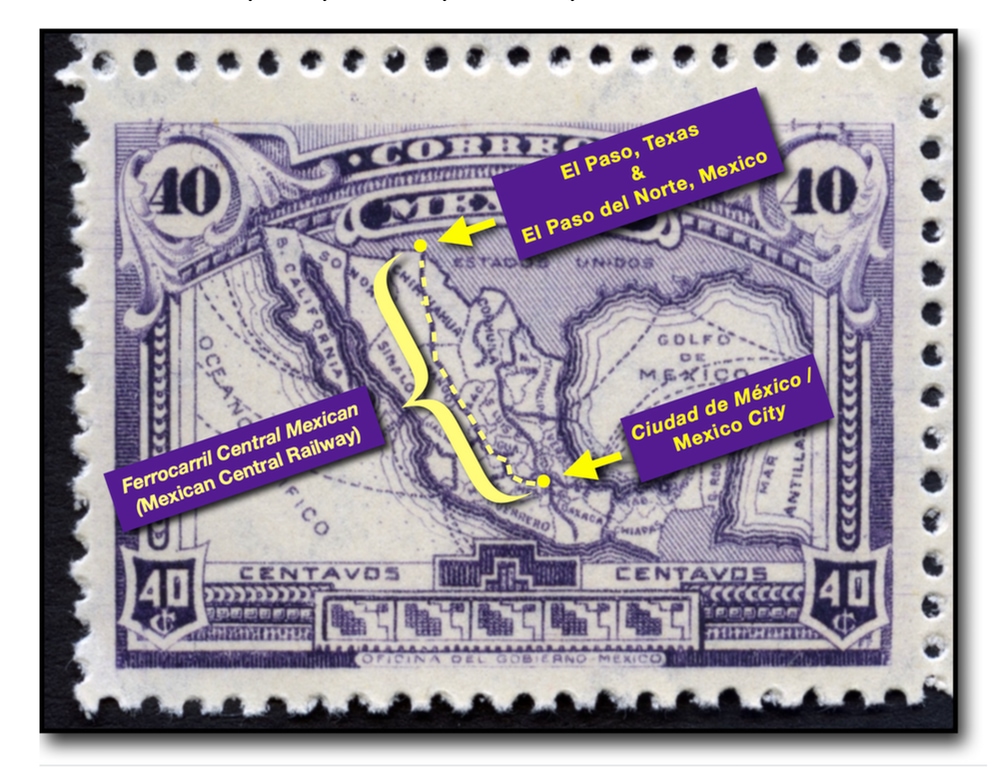

In 1915-1916, Mexico issued a 40-centavo stamp picturing a map of Mexico which highlights the various railroads serving Mexican travellers. This block of four is interesting from a philatelic standpoint. Note the unusual mis-alignment of the two stamps at the right, which are slightly higher on the sheet than the other two stamps.

The following image, cropped from the lower-right block of four stamps shown above, documents the route of the Ferrocarril Central Mexicano between El Paso and Ciudad de Mexico:

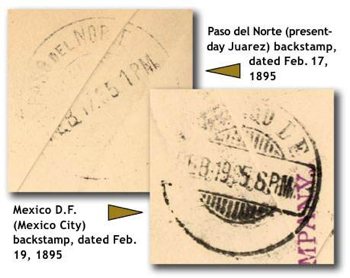

The back of the cover includes three backstamps — postmarks applied to a piece of mail by the receiving post office or by a post office handling the piece while it is in transit. Backstamps are usually on the back of a cover, but they can be on the front, which would make them frontstamps!

The backstamps on the back of the Azure Mining Company cover, shown below, provide information about its provenance:

• The postmark, dated February 17, 1895 at “PASO DEL NOR E” (Paso del Norte), shows that the cover transited through that city. (It was common practice until the 1950s for post offices between the originating and receiving post offices to apply a postal markings called transit marks to facilitate record keeping.)

• A receiving postmark, dated February 19, 1895, with the readable letters “...ICO D.F.” A complete strike of this postmark would doubtless read, “MEXICO D.F.” (D.F. stands for Distrito Federal, or Federal District, the official name of Mexico City.)

• A final postmark on the back reads CARTERO #7 — POSTMAN #7 — an instruction that the letter was to be delivered by the letter carrier who was responsible for a particular mail route.

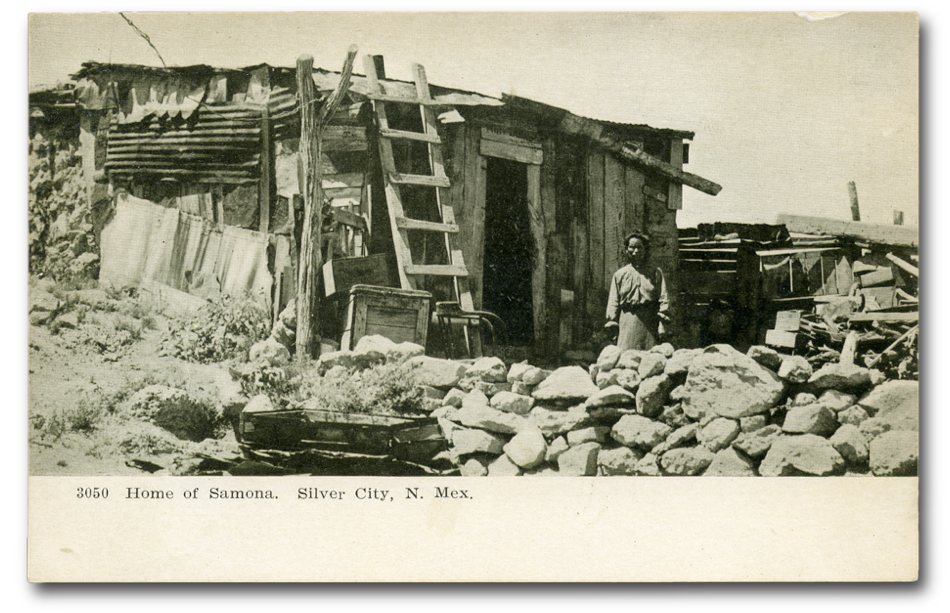

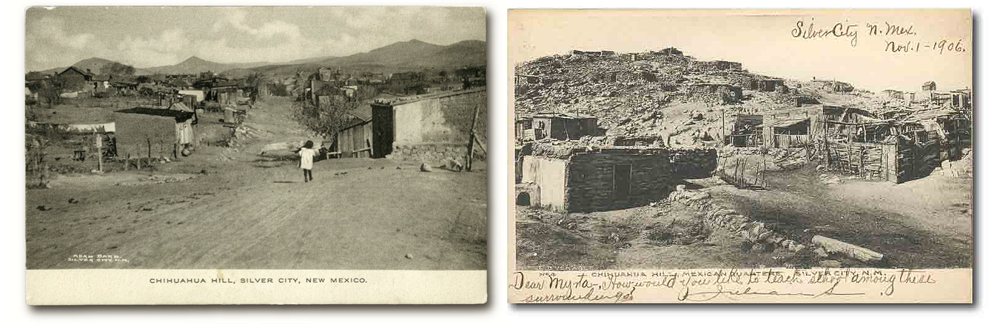

Is the Azure Mining Company cover rare? Of course! Although Silver City has always loomed large in mining circles, it has never had a large population. In 1895, when the Azure Mining Company posted its letter to Mexico City, the population was probably around 2,500, based on figures of 2,102 in the 1890 census, and 2,735 in the census of 1900; in that decade, many of Silver City’s citizen, perhaps a majority of them, were poor, illiterate labourers unlikely to use the mails. (Silver City’s 2020 census counted 9,704 residents, down from a high of record high of 10,683 in 1990.)

Few if any Mexican-Americans in Silver City got rich because of the area’s mineral wealth, but the same cannot be said of the city’s Anglo population: the homes of mining company executives, engineers, geologists, and various entrepreneurs, politicians would have been the envy of many wealthy people in the East.

Covers and postcards from the early period of Silver City’s history are relatively scarce, and ones representative of the mining industry aren’t often seen. Even if the Azure Mining Company cover is rare, it is not necessarily valuable. In postal history collecting, value is in the eye of the collector, and the laws of supply and demand apply: If there is no demand for my Azure Mine cover, then, ergo, it has no value. It is, however, valuable to me. And no, it’s not for sale!

For additional information on the Azure Mine and the history of Silver City, New Mexico:

The Azure mine produced world-class turquoise

and

Remembering Silver City.

-

Tied Stamp — A stamp is said to be tied to a cover when the cancellation or other postal marking extends over both the stamp and the paper of the envelope or wrapper. Stamps can also be tied by the obvious aging of the mucilage or glue that affixes them to the paper, or obvious aging or damage that affects both the stamp and paper. Tying provides a degree of confidence that a cover has not been tampered with to increase its value. ↩︎

-

The initials “CDS” stand for “Circle Date Stamp, often and incorrectly called “CDS cancels,” Circle Date Stamps have often been used to cancel stamps. Their name, of course, comes from their circular design and their inclusion of the date (and often the time of day) when the cover was postmarked. ↩︎

-

Cork Killer — The term “cork cancellation” refers to a handmade cancellation device designed to apply a “killer” postmark in dark ink to a stamp to render it useless as postage. The devices were not necessarily made of cork, which was not tough enough to stand up under repeated use, but of hard rubber or wood. Postmasters often cut decorative designs into the cancellation device; killer cancellations with artistic or otherwise interesting designs are highly sought after by collectors and often fetch high prices. ↩︎