The Two Thousand Yard Stare How 12 incidents in South Vietnam changed my universe

I was nearby in our bivouac area (“Camp Hansen”) in Quant Ngai province, when a Marine was killed instantly when his friend’s M-14 was discharged accidentally. (Early February, 1966, Operation Double Eagle I)

I witnessed the death by “friendly fire” of an ARVN soldier by a Marine rifleman. (Early February, 1966, Operation Double Eagle I)

I cared for a Marine whose right arm was almost amputated by a rifle bullet fired by a sniper from a nearby stand of trees. At the time, we were sitting in an open area where we had stopped for lunch. I was only a few yards from him when he was shot, and I was the first corpsman to reach him. (Early February, 1966, Operation Double Eagle I)

I witnessed the killing of the young Viet Cong and the subsequent dishonoring of his body. Late February, 1966, probably Operation Double Eagle II)

I helped care for a young Marine whose legs were blown off by a mine. I was only a few yards from him when he tripped the mine. (Late February, 1966, probably Operation Double Eagle II)

I witnessed the physical and psychological abuse of prisoners and their families by Popular Forces personnel. These paramilitary forces were ill-trained, poorly armed men who used tactics similar to those of the Viet Cong. (Early February, 1966, Operation Double Eagle I)

I was ordered to stand guard over an elderly farmer, and to shoot him if he tried to escape. In the meantime, an officer staged a mock execution of a younger man, possibly the older man’s son, in order to extract information from him. (Late February, 1966, probably Operation Double Eagle II)

I witnessed the machine-gunning, without cause, of an elderly Vietnamese man. (Late February, 1966, probably Operation Double Eagle II)

I came under sniper fire on two other occasions, but there were no casualties in those incidents. (February, 1966, Operations Double Eagle I & II)

Each of us, in our journey through life, develops a narrative of the events that shape us. That narrative, that story we tell ourselves about ourselves, gives us our sense of self and depends entirely on our memory. We are, in a very real sense, the sum of what we recall about our past. Those recollections allow us to understand our present, to the extent it can be understood, and to cope with the future, to the extent that we can cope with future events. Without memory, our past doesn’t exist. In fact, without memory, we don’t exist except as meaningless collections of bone, blood, and tissue without meaning.

For a moment, try to imagine that you can recall nothing of the past — it’s an impossible task, of course, since you do recall much of your past. Here’s a more realistic assignment: for a moment, try to imagine that you cannot remember something significant in your past — a former lover’s face, your first job, your parents, your home address. Most of us do have trouble remembering elements of our past. In fact, we would probably suffer a psychotic break if we were unable to forget details and at least some of the larger elements of our experience. We could not cope with the flood of information that would threaten to overwhelm us every waking moment. And here is the crux of the issue: many people in our society are, in fact, unable to forget incidents and circumstances in their past that are best forgotten. Among them are women who were raped; people who endured sexual, physical, and emotional abuse in childhood; victims of nearly fatal accidents; civilians who have endured the wars brought on by their leaders, and, finally, men and women who have survived the crucible of combat. It is the last of these groups which is the concern of this paper.

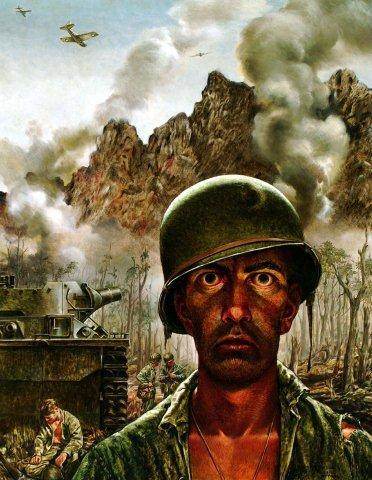

The Thousand Yard Stare One of the tragedies of our world is that we have always — intentionally and irrationally — plunged young men and not a few women into wars. If they survive any physical wounds (and most wounded soldiers do survive these days), they may well face another challenge, that of dealing with the new person who now exists in their body. Their experiences have irrevocably altered their sense of who they are. They will struggle to fit into a world that is not the same world they left when they went to war. Their experiences in combat have shattered what they thought they knew of the world, and forced them to accept new realities:

uneven

self and challenge what they thought they knew about themselves and about the world they live in. More significantly, the situations they find themselves in are very likely to cause trauma which will, in a literal sense, irrevocably change who they are and who they will remain to the end of their days. I am one of those soldiers who was irrevocably traumatized by war.