Triumph & Tragedy ~ The story of the KLM DC-2 Uiver (Part 4)

The Uiver’s first — and last — commercial flight

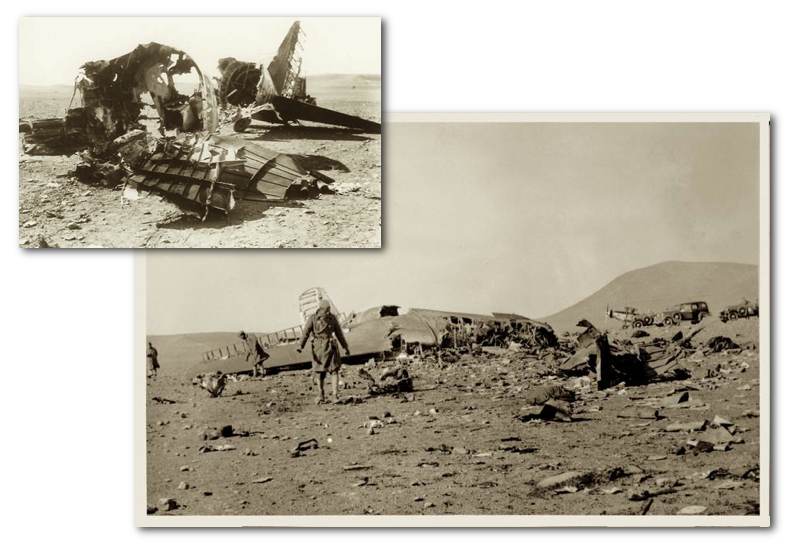

A photograph of the Uiver wreckage clearly shows damage from both the impact with the earth, and from the fire. Note that the fabric covering of the rudder, which was covered with linen impregnated with highly flammable butyl dope, has burned away.

At the right, a photo from the Uiver crash site shows one of the airliner’s two propellers. The blades, bent backward and curved to the left, show that the aircraft was under power when it crasged.

The extreme violence of the crash not only resulted in the destruction of the Uiver and the death of its passengers and crew, but its cargo of cherished Christmas mail also became a victim.

The Uiver was carrying 348 Kg of mail in 10 mail bags, of which only three were undamaged. The mail in the seven other mailbags was partially burned and/or damaged by oil, water, and mud. Searchers reported that the crash site was littered with envelopes. For some 40 Kg of mail, neither the sender nor the addressee could be determined; with the intercession of Iraqi postal authorities, some 700 postal items were returned the Netherlands and, to the extent possible, to the senders.

Uiver covers re not rare, but surviving covers are found in every imaginable condition. One of the interesting things about collecting crash mail (also known as adversity mail or interrupted mail, is that its commercial value is inverse to its condition: The rougher the condition, the greater the value (as long as it can be verified as mail from a particular crash).

Airmail letters carried by KLM Airlines in the1930s had to be franked with special airmail stamps in addition to regular postage. The distinctive triangular stamps feature a Fokker aircraft like those used by KLM in the airline’s early days; the Uiver was the first non-Fokker aircraft purchased by KLM.

Although the airmail stamps were issued by Netherlands post, all revenue from their sale went to KLM as a subsidy.

Mail recovered from crash sites normally is stamped by postal officials to indicate that its delivery was slowed or made impossible because of the accident. No such markings exists on Uiver crash mail; identification of undamaged covers depends on the impression of the special rubber-stamp cachet, showing a stork flying through a Christmas wreath, on town cancels with readable dates, and, often, a printed cachet showing the Uiver flying through a Christmas wreath. Most Uiver crash mail is also inscribed “per Uiver.”

The undamaged Uiver cover at the left does not bear the common printed cachet showing the Uiver and a Christmas wreath, but it does have the rubber stamp cachet and appropriate cancellations. Below, a detail showing the back of the cover, with a backstamp indicating receipt at Tjepoe, Java, on 29 December 1934.

Some Uiver crash covers were soaked in engine oil, like this one. It was also soaked with water, as evidenced by the missing stamp and faded rubber stamp cachet. The author of the enclosed letter, a student who is living with a family in Netherlands, complains to his parents in Java about both the poor food that his host family provides.

Why the Uiver crashed

hen an airliner falls from the sky, newspaper headlines shout about “Pilot Error,” “Freak Weather,” or “Mechanical Failure.” However, airliners rarely fall from the sky for one reason alone. Nearly always, such disasters result from a complex cascade of circumstances. So it may have been with the Uiver.

Weather The proximate cause of the crash of the Uiver was most likely a violent thunderstorm. The “speeded-up” Christmas flight took place in the late autumn when a huge volume of moist Atlantic air flows eastward across the Mediterranean Sea. Depressions develop in Saharan Africa and storm fronts, including cyclonic storms, track eastward across the Levant and into Iraq.

he Uiver was destroyed almost completely by fire, cause unknown. Early reports blamed lightning. Only very rarely does lightning cause serious damage to aircraft, but it has occasionally knocked aircraft out of the sky. • A lightning strike on an aircraft tends to travel from one extremity — a wing tip, for example — to another, such as the tail or the thin trailing edges of control surfaces. In modern aircraft, static wicks bleed static electricity charges safely away from the aircraft, but static wicks were unknown when the DC-2 was built. In the case of a lightning strike, it is likely that metal parts of the aircraft could become hot enough to ignite anything flammable. • Flammable materials used in the DC-2 included the control surfaces, which were coated with highly flammable butyl dope. A lightning strike might have ignited the Uiver’s rudder, elevator, or ailerons and caused the crew to lose control.

This photo of the remains of the Uiver clearly show the destructiveness of the fire that followed or perhaps even led to the crash of the aircraft. Note that the covering of the metal frame of the rudder has burned away.

Ernest K. Gann flew the DC-2 for American Airlines. Among his comments in his book Flying Circus, any one of which could have a bearing on the crash of the Uiver: “While flying in the rain the cockpit windshields leaked so badly that the effect within was that of a seriously depth-bombed submarine.” (In a torrential rainstorm such as that in which the Uiver crashed, a leaking windscreen could have presented a difficult distraction to the crew.) “For reasons which are still obscure, consistent good landings in a DC-2 were impossible, or if claimed, a proof of that man’s self-delusion.” (There have been suggestions that Captain Beekman attempted a landing in the desert. It appears that that would have been difficult even with having to contend with a storm.) Gann also notes that stability problems led to a novel solution, at least in the DC-2s he was familiar with: the floor of the compartment just forward of the tail, used for mail and luggage, was permanently lined with sandbags weighing a total of 1,000 pounds. (The Uiver probably did not have the benefit of sandbags in its tail section.)

hat the Uiver might have come to grief because of a thunderstorm is not surprising. Even today, all thoughtful aviators fear the towering storm cells characterized by cumulonimbus clouds, which can literally tear any aircraft apart and have often done so.

Many airline tragedies have been caused by encounters with these storms, which have killed even at a distance: Lightning, sudden changes in wind direction known as wind shear, and microbursts — local, high-speed, downward flowing columns of air — often occur several miles away from the visible storm activity. Icing of wings, tail surfaces, and even propellers often results from the conditions within and near these storms. The ice, which can even form near the ground, diminishes the ability of the wings to sustain lift. Torrents of rain can destroy visibility from the cockpit; the hail stones pounding on the fuselage can distract the crew; lightning can blind them. The Uiver, possibly losing altitude because of icing, may well have been hammered earthward by irresistible forces, its crew utterly unable to exert any control.

Cumulus congestus clouds, in southwestern New Mexico. These clouds develop in unstable atmospheric conditions which cause warm, moist masses of air to rise quickly to higher altitudes. They produce moderate rain or snow showers, and may quickly grow into the airman’s nightmare — cumulonimbus incus clouds.

At the left are two of 15 stamps from a set of pictorial “Cloudscapes” stamps issued by the United States Postal Service in 2003. At the far left, cumulus congestus; at the near left, cumulonimbus incus. (Incus is Latin for “anvil”. Cumulonimbus incus clouds are known as “Anvils of the Gods”.)

“Pilot error” is often blamed for airline disasters, and while pilots do make fatal errors, disasters normally result from a cascade of seemingly unrelated events. These human factors may have played a role in the crash of the Uiver: • Captain Parmentier, hero of the MacRobertson race, refused to fly the Uiver on its fast Christmas trip to Netherlands Indies. He and the other KLM pilots were well aware that December was a particularly hazardous time of year to fly in the Middle East and Asia. He also was concerned that the DC-2, despite its excellent performance in the MacRobertson race, had not yet proved itself. • Captain Beekman, second choice for the flight, also refused on similar grounds, but he had less clout than Parmentier. KLM President Albert Plesman told Beekman that he would fly the Uiver to Netherlands Indies or he would be fired. The world was still deep in the Depression, and jobs for pilots were hard to come by; Beekman agreed to fly. • Captain Beekman, as head of the pilots’ union, was in negotiations with Plesman late into the night before the Christmas flight. He must have been sleep deprived when he took off at 4:30 a.m.; when the Uiver left Cairo, he had been on duty more than 17 hours. • The success of the Uiver’s Christmas flight was vitally important for KLM’s (and Albert Plesman’s) public image. Human beings often lose sight of common sense; even in the face of obvious danger, we will risk all. We also seem to be programmed to use the technologies we develop and to honor the social institutions we join. When the Uiver lifted off from Schiphol Airport, Captain Beekman, despite his misgivings, was probably committed to completing the flight in the best traditions of KLM Airlines.