Box 28, Arenas Valley, NM — A tiny country post office played a big role in my youth (Part 2)

Olga Harper resigns, Joe Moore becomes postmaster

Five years after the opening the Arenas Valley Post Office, Mrs. Harper resigned as postmaster and closed her convenience store. The post office was relocated to an old building just one lot to the east on the same side of Arenas Valley Road. Arenas Valley resident Joe Moore was named acting postmaster on April 30, 1952.

Both Olga and Joe had to jump through a government hoops, filling out and signing the federal Bureau of Post Office Operations Form 971 to make the transition. The completed form confirms that the Arenas Valley Post Office was a small post office indeed, with a stock of stamps, postal cards, stamped envelopes, etc. worth just $27.48, and cash $22.52 in cash.

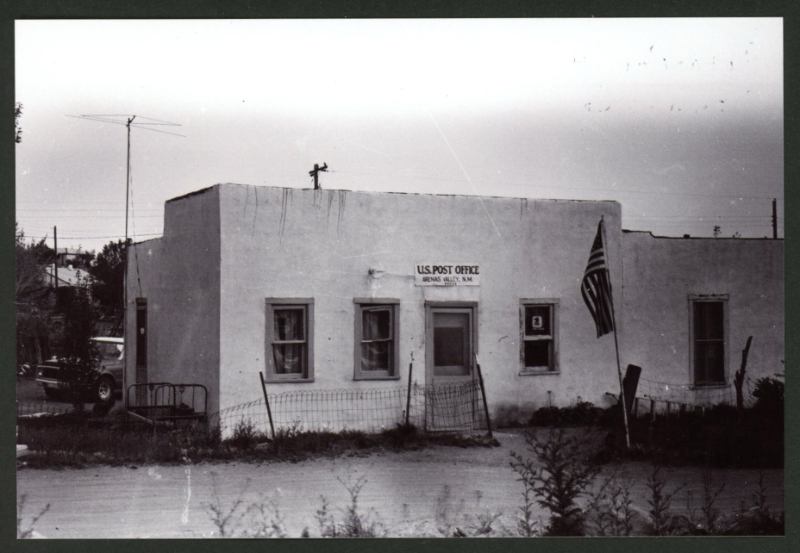

The “new” Arenas Valley Post Office was a nondescript, stuccoed structure of indeterminate age and heritage. Before it became a post office, it housed a small convenience store where my friends and I could buy pop and other snacks. One of my favourite purchases was chocolate-flavoured soda pop; I don’t recall the brand, and I never saw it again after the store closed to make room for the post office.

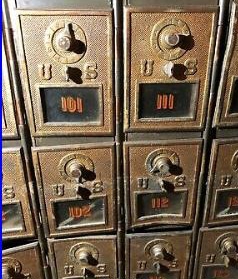

The convenience store’s transition to post office was made public by the addition of a simple sign above the door and the installation of ornate mail boxes and a wicket behind which the postmaster greeted his customers, sold stamps and money orders, and distributed letters and junk mail — very small amounts of junk mail compared to today’s flood! — to the mail cubbies. A few “WANTED” posters announced that post office was an institution of the federal government.

Joe and Hazel Moore

I remember the new postmaster, Joe Moore, as a tall, gaunt, uneasy man, but quiet in a friendly sort of way. He and his family lived in a small house behind the post office. Joe never looked well and indeed was not well: he was apparently suffering from polio, ended up in an iron lung, and died October 23, 1952. Joe’s wife, Hazel V. Moore, succeeded him as Arenas Valley’s Acting Postmaster on June 3, 1953. I assume that his Hazel served as interim postmaster before being named acting postmaster on June 3, 1953 and acting postmaster just 26 days later.

Hazel, a thin slip of a woman with dishwater-blonde hair, was mother to three waif-like little kids, Jimmy, Charlie, and Suzy. Hazel always seemed tired and sad, but she was a kind woman who patiently endured the limitless curiosity of my friends and me about the larger world that she represented.

In those days, we were taught to address women according to their marital status, which in Hazel’s case would have been “Mrs. Moore”. If she hadn’t been a married woman, we would have said “Miss Moore”. But my friends and I were so comfortable with her, and she with us, apparently, that we automatically called her Hazel whether we were talking about her or addressing her directly. (My mother’s given name was Hazel, too, but my friends were never have dreamed of addressing her as anything but Mrs. Ingraham.)

My friends and I assumed that Hazel took special interest in all of our activities. Danny Sanders and I once proudly entered the post office to show her our latest prize, a large, angry bullsnake captured in our endless hunt for animals which might have become pets but never seemed to like the idea. Hazel’s response shocked us, and probably the snake, too: She screamed a full-throated, adrenalin-charged, phobic, death-defying scream. Danny and I retreated with our snake, alarmed that our invasion of the post office might have killed Hazel.

Hazel’s daughter, Suzy, told me in an email several years ago that Hazel, who died in 1985, served for 33 years as Arenas Valley’s postmaster. When she retired, she was replaced not by another postmaster, but by an “Officer-In-Charge,” Francis M. Torres, who was appointed on January 15, 1985.

Francis M. Torres Officer-In-Charge 01/15/1985 Discontinued on April 20, 1987; mail to Silver City (Postal Bulletin 21616)

By that time, the post office had been moved out to Highway 180, about two miles from Central, whose name was changed to Santa Clara in 1996. Soon after the move, the ugly old building that had was demolished and replaced by a double-wide trailer.

In eighth grade at the Elementary Laboratory School, operated for the benefit of student teachers at New Mexico Western College (now WNMU, the University of Western New Mexico), I wrote a descriptive paragraph about the Arenas Valley Post Office for my teacher, Miss Inez Rhodes. My wife, Susan, recently re-discovered the paragraph in an old scrapbook; coincidentally, it is dated October 4, 1956, her 11th birthday.

Miss Rhodes awarded me with an “A” for content and an A- for “mechanics” — spelling, grammar, punctuation, layout, and I suppose, my barely readable penmanship. If you wish, you may try to read the original in a larger image, but the following transcription will be kinder to your eyes:

Box 28

Box 28, my family’s mailbox, was one of several cubbyholes or mail cubbies to the left of the post office’s ornate wicket, featuring decorative, cast-metal doors with two-factor alphabetic combination locks. We unlocked it by twisting its single pointer a full revolution or more clockwise to N, then counter-clockwise to C. Oh to still have such simple passwords! Once, when Hazel was absent, I opened box 28 and reached into and through it to see if I could pull mail out of other, nearby boxes. I could! Easily! I didn’t take a thing. I didn’t even look at my potential “loot” — I was no thief, except in fantasy.

Stamps at the wicket

I joined the Boy Scouts of America in the early 1950s, about the same time that two boys about my age, sons of one of my dad’s business associates, introduced me to stamp collecting. I soon became a regular customer at the post office, anxiously anticipating the release of new stamps and hoping to earn a stamp collecting merit badge (which I did).

Hazel played her role perfectly. From behind her wicket, she would show me new issues and would sort through panes of stamps to search for perfectly centred copies. Hazel, unlike most of today’s so-called “postal clerks,” actually understood what collectors wanted and always separated stamps from their sheets with surgical precision. I usually bought single stamps for my Ambassador Album for Stamps of the World and plate blocks of four, which I stored in small stock book with pages consisting of glassine pockets.

Stamps on approval

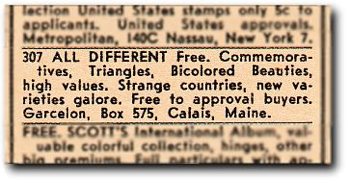

As a Boy Scout, I received the monthly Boys’ Life magazine, now called Scout Life. When each new issue arrived, I skipped the articles and other advertising, and went straight to the classifieds where there was always a full page and sometimes more of classified ads for stamps on approval.

I spent most of my allowance — 50 cents a week — on approvals from such companies as Jamestown Stamp Company, H.E. Harris, Garcelon Stamp Company, Kenmore, and Gadsden Stamp Company.1 I soon learned that the Gadsden company was “headquartered” in a bunagalow just a block or two away from my grandparents’ almost identical bungalow in Hurley and that its owner was also the president of the Hurley Stamp Club, which is the first stamp club I joined.

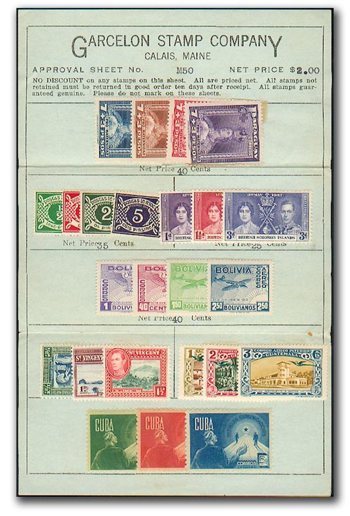

The business model for approvals was based on trust. The approval dealers mailed inexpensive stamps to their clients, usually in short sets without the high-value stamps, packaged in printed glassine envelopes or attached to sheets with stamp hinges. The collector selected the stamps he or she wanted and returned the remainder along with payment. It was an honour system, one that most collectors upheld although I must confess that I did not always promptly return the stamps I didn’t want and payment for the stamps I wanted to keep.

The approval sheet at the left came from the well-known Garcelon Stamp Company, located in St. Stephen, New Brunswick. Much of Garcelon’s business came from American customers, however, so their approvals for customers were sent from Calais, Maine, just across the St. Croix River from Calais. At one time, Garcelon employed 150 people who sent approvals around the world. Most of the approval companies that sent approvals by mail are long gone, but a few still exist. Today, most stamps are sold by companies who rely on high-quality scanned images to interest potential buyers.

Not long after I started collecting stamps, I realized that some stamps reflected my most memorable experience to that time, namely my first airplane ride. Shortly before my family moved to New Mexico, my Dad arranged for Helen and me to have a flight in a Piper Cub over Savona. I have been nuts about airplanes ever since, so it’s not surprising that one of the most exciting selections of approvals I received included a mint set of eight Hungarian airmail stamps, issued in 1954 and picturing various aircraft, model airplanes models, and a parachutist. When I saw that the set included a stamp two MiG-15s flying in formation, I couldn’t not purchase it.

Not long after 1957, when my family moved from Arenas Valley to Silver City, and I started high school, stamp collecting faded into the background of my life, replaced by a growing interest in girls, photography, girls, some of my classes (band, science, geometry, journalism), and girls. Military service in Vietnam, university, marriage, husbandhood, fatherhood, emigration to Canada, and my career as a teacher put more and more distance between me and stamp collecting until 1980 or 1981. That was when teachers in my elementary school — Wildwood School in Prince George, British Columbia — were “encouraged” — coerced? — into sponsoring extracurricular activities.

Thumbs down for coaching, thumbs up for stamp collecting

Our principal, Geoff Eacott, suggested that we teachers might consider coaching a basketball or baseball team. The last thing I wanted to do was to sponsor any team sport. I’d had an aversion to locker rooms and “team spirit” since elementary school, but I had an idea for something new at the school: I would start a stamp club!

I soon had a room full of enthusiastic new collectors who seemed to have found their niche: They were thoughtful, academically inclined but not necessarily top students, more introverted than extroverted, and quick to learn that stamps aren’t just colourful little rectangles of paper, but are artifacts that reveal much about our world. And something that I didn’t anticipate — the student’s’ enthusiasm for stamp collecting reignited my own interest in stamp collecting. Since my wife, Susan, and I had emigrated to Canada in 1969 and intended to become Canadian citizens, I bought a Canadian stamp album and began learning more — much more —about our new country through its postage stamps.

And then came covers…

It wasn’t long before a local stamp dealer introduced me to cover collecting. Covers — “dirty, old, used envelopes” — offer what stamps alone cannot: Every collectible cover has a story to tell. Its stamps or lack of stamps tells the collector how it was carried through the mail stream and what it might have enclosed. Hand-written or typed addresses and return addresses reveal the origins, destination, and intended recipient or recipients. Their cancellations and postmarks, penciled notations, paper type, size and condition of envelope, general condition, and sometimes — if you’re lucky — the contents all work together to provide detailed if incomplete histories of covers.

No cover can reveal its entire provenance,2 but covers often include enough clues to put the collector onto an interesting story. That’s the case with one of the three Arenas Valley covers in my collection, sent by an M.J. Fell to the Gulf Oil corporation in Houston in the late 1950s or in the 1960s. When I purchased the cover for a few dollars from an American dealer I had no idea who M.J. Fell was or why he was mailing a corporate letter to Gulf. Now I know who he was and why he was sending the letter, and I know that in elementary school I used to ride the school bus with his eldest son!

-

The Gadsen Stamp Company was no doubt named after the Gadsden Purchase of 1854, the treaty between the United States and Mexico that expanded the U.S. territory by 29,640 square miles in present-day Arizona and New Mexico. It was motivated by the desire for a southern transcontinental railroad and resolved some border disputes. ↩︎

-

Provenance refers to the origin or source of an object, artwork, or document. It describes the history of ownership or custody of an item, and is used in the context of authentication or verification of an item's authenticity or legitimacy. ↩︎