A Comet Falls ~ Disaster at the dawn of the jet age

On the evening of April 8, 1954, a South African Airways de Havilland Comet 1 jetliner, registered G-ALYY, took off from Rome’s Ciampino Airport, bound for Cairo and Johannesburg. Half an hour later, ground controllers lost contact with the Comet, which had disintegrated in flight.

The loss of the Comet, just three months after another Comet was lost, triggered an investigation that came to focus on a little-understood hazard of jet flight — metal fatigue caused by repeated flexing of vulnerable portions of the fuselage as it was pressurized as it ascended and depressurized as it descended.

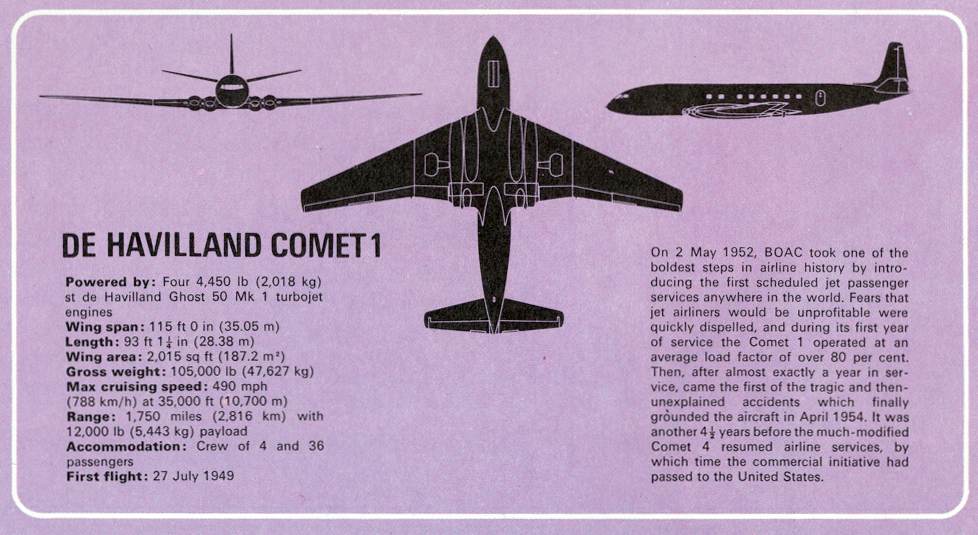

The Comet 1 was the first jet-powered airliner, capable of flight “above the weather” (a conceit that would eventually be proved wrong) at a cruising speed of 740 kilometres per hour (460 miles per hour). The fastest propeller airliner at that time, the Lockheed Super Constellation, cruised at 547 kilometres per hour (340 miles per hour).

Routine radio reports from the South African Comet during the first 25 minutes of its flight were…routine! At 19:07 GMT, while the Comet was still climbing to its cruising altitude, the crew contacted Cairo by long range HF radio to report their ETA in Cairo — 21:02 GMT. That was the communication with the Comet: repeated attempts to regain contact by both Cairo and Rome were futile.

A search began at dawn the following day in the Tyrrhenian Sea. A patch of oil was found some time later about 110 kilometres (68 miles) east of Naples; bodies and wreckage were found 48 kilometres (30 miles) south-east of the island of Stromboli, near the “toe” of the Italian peninsula.

Crash investigators determined that the Comet had disintegrated in the night sky at 11,000 metres (36,000 feet), instantly killing the South African crew of seven and the 14 passengers. It was the second Comet disaster in three months: on January 10, all 35 passengers and crew on board a British Overseas Airways Corporation Comet, G-ALYP, died when their aircraft also disintegrated in flight and crashed into the Tyrrhenian Sea near the island of Elba, about 300 miles (482 kilometres) northwest of the South African Airways Comet crash area.

aExhaustive tests on another Comet 1 eventually determined that metal fatigue, not well understood at that time, had caused explosive decompression which destroyed both the BOAC and the South African Airways Comets. The tests demonstrated that cracks had developed in the fuselages of the ill-fated Comets, at the corners of rectangular doors and windows as the aircraft were subjected to repeated pressurisation cycles. Because the Comets flew at high altitudes, their fuselages were pressurised for passenger comfort and safety at the start of each flight and depressurised as the planes descended. Their riveted construction couldn’t contain the stretching forces at work on the aircraft’s stressed hull. The Comets had literally blown apart at the seams.1

The two 1954 Comet crashes ended Great Britain’s dream of dominating the global market for civil airliners. De Havilland redesigned the Comet to reduce metal fatigue, but they were too late: the American company, Boeing Commercial Airlines, first flew its prototype Boeing 367-80 (known as the “Dash 80” at Boeing) in July, 1954. Its derivative, the Boeing 707 jet liner, first flew in December, 1957. It would soon became the standard passenger jet for airlines around the world. Although De Havilland produced 90 more Comets, they were never able to compete with the 707.

The 707, along with other new jetliners, spelled the end of the era of slow, uneconomic, propeller-driven airliners on long-distance flights. Ironically, three and half hours before the South African Airways Comet came to grief, one of those propeller-driven airliners, a Trans-Canada Airlines North Star, collided in flight with a Royal Canadian Air Force Harvard trainer over Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, killing everyone on board, and a woman on the ground. That disaster is chronicled in my web page titled, North Star Falling.

The in-flight destruction of the early Comets cast a temporary pall over commercial aviation and especially on jet flight; no passenger could calmly consider boarding an aircraft which might disintegrate miles in the air. But as older, propeller-driven airliners were gradually replaced by improved jetliners, it became increasingly clear that jet flight was demonstrably safer than flight had ever been before the “jet age”.

-

In both cases, pressure tests involving an undamaged Comet fuselage submerged in a huge water tank showed that the thin, laminated duralumin skin at the corners of square windows had developed microscopic cracks because of the practice of punching rather than drilling holes for rivets. Under flight conditions, the differential air pressure between the interior of the aircraft and the exterior caused the fuselage to bulge slightly while climbing to cruise elevation and deflate slightly while descending.

In the case of Comet G-ALYY, the cracks increased in size until the explosive rupture occurred after only 900 take-offs and 899 landings. Improved construction techniques (drilling instead of punching rivet holes and using round rather than square windows) resulted in the production of much more reliable aircraft.

A Comet 4C, registered as XS23 and flown by the British Ministry of Technology for radio, radar, and avionics trials, made the last documented Comet flight in March, 1997. ↩︎