North Star Falling — Death rains from the sky over Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan (Part 1)

Updated January 24, 2017

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8

Sixty commercial airliners fell from skies around the world in 1954. That’s shocking by today’s standards, but it was actually a slightly better year than average: Between 1950 and 1959, an average of 61 airliners crashed annually.

One of those 60 airliners that crashed in 1954 was a Canadian C-4 North Star flown by Trans-Canada Airlines and registered as CF-TFW. The C-4 was a variant of the Canadian Canadair DC-4M, itself a variant of the famous Douglas DC-4 transport. On the clear spring morning of Thursday, April 8, 1954, over the small city of Moose Jaw1 in south-central Saskatchewan, the North Star and a Royal Canadian Air Force Harvard trainer, registered as RCAF 3309, collided, killing everyone on board both aircraft as well as a woman on the ground. It shouldn’t have happened: the visibility that morning was was perfect, and both aircraft were in sound condition and flying on approved routes.

Disaster over Moose Jaw

Canada’s worst aviation disaster to that time

Thirty-seven people died in the Moose Jaw crash, including 31 passengers and four TCA crew members on board the North Star, the student pilot of the Harvard, and one woman on the ground. It was the worst aviation accident in Canada up to that time.

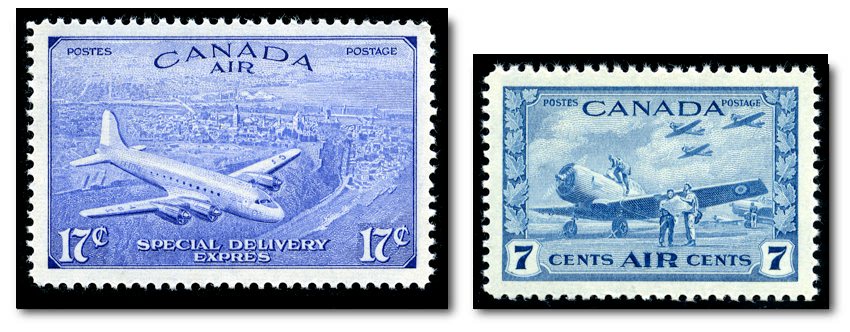

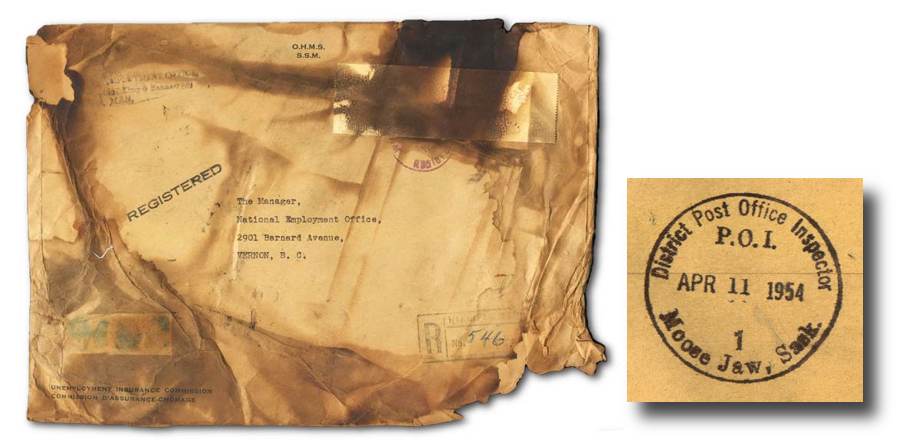

The North Star was carrying more than a 454 kilos (1,000 pounds) of mail destined for Vancouver and points beyond. Much of it was destroyed or damaged by fire and water. Pieces of mail that have been damaged in aviation, rail, and shipping disasters are classified by philatelists as “adversity mail”. Individual envelopes (called “covers”) resulting from aircraft accidents are called “crash covers”.

A cascade of unforeseen — and avoidable — events

Most aviation crashes result from a cascade of unforeseen events: pilot inexperience, bad weather, poor maintenance procedures, mechanical failure, errors made by pilots and/or ground control personnel, fatigue, obsolete equipment, outdated or inadequate procedures, terrorism, even suicide of a crew member or passenger. But the collision over Moose Jaw didn’t fit easily into any possible scenario: The weather was fine, and the aircraft were well-maintained and functioning normally, on time, and on course. It just didn’t make sense that qualified pilots could fail to be aware of an impending collision. But one significant factor came to light during the accident investigation: the flight plans, approved by the Canadian Transport Board, were potentially disastrous and proved to be fatal.

Situation Awareness

Today, pilots rely on various automated systems, including Airborne Collision Avoidance Systems (ACAS) and Airborne Separation Assurance Systems (ASAS), both of which operate independently of ground-based equipment and air traffic control in warning pilots of the presence of other aircraft that may present a threat of collision. ACAS is used to describe short-range systems intended to prevent metal-on-metal collisions; ASAS is being describes longer-range systems used to maintain standard en-route separation between aircraft. In 1954, no such systems existed — pilots were to maintain situation awareness2 of their own aircraft and their surroundings.

We will never know what the pilots of the TCA North Star and the RCAF Harvard experienced in the moments before their collision, but it’s possible that it occurred without any of them, especially the co-pilot in the right-hand seatof the North Star, being aware of imminent danger.

This web page provides detailed information about the two aircraft involved in the accident, about their crew and passengers, about the events leading up to the collision, and the aftermath of the collision, both in the air and on the ground. Part 7, illustrated with several crash covers and other documents related to the crash, deals with the challenges that postal officials faced in the days after the collision.

Next, in Part 2: The North Star airliner was a distinctive Canadian hybrid of three American airliners, including the famous Douglas C-54 used by Royal Air Force Ferry Command to transport soldiers and war matériel from North America to war zones around the world.

-

The origin of Moose Jaw’s name is uncertain. According to Arok Wolvengrey of the First Nations University of Canada, it is likely based on the Cree word for moose jaw, mōsocāpiskan, and may have first been applied to a local creek that supposedly resembled the outline of a moose's jawbone. ↩︎

-

Situation awareness describes a pilot’s awareness of his surroundings and past, present, and future circumstances. The term “situation awareness” was adopted to describe the processes of attention, perception, and decision making that together form a pilot’s mental model of the current situation and possible future scenarios. Situation awareness was developed as a concept among the American pilots who engaged Russian MiG-15s in the Korean War. ↩︎