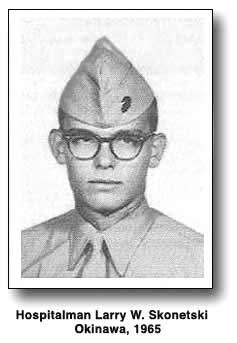

Corpsman up! — Hospitalman Larry Skonetski in Vietnam (Part 1)

I wrote this revised version of Corpsman Up — Doc Larry Skonetski late in 2008 when, after almost 43 years, I finally managed to contact the navy hospital corpsman who had briefly been the most important person in my life. It was an emotional reunion.

In 1966, on a small hill in South Vietnam, Larry briefly became the most important human being in my world: Larry was my fellow corpsman in Lima Company, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division; a Communist rifleman had shattered my femur with one shot; Larry came to my aid and stayed with me until I could be evacuated. When I heard his voice again on the telephone, all those years fell away; once again we were comrades in arms. I was saddened, however, to learn that he was dying of lung cancer, probably as a result of exposure to Agent Orange.

Larry lost his his final battle on April 19, 2009. He was 63. Semper Fi, Larry. I miss you.

Bob Ingraham

Vancouver

When a communist rifleman shot me through my right thigh, my first words were, “Ski! The bastard shot me!” “Ski” was Hospitalman Larry W. Skonetski, and I knew that he was nearby. It happened on a sunny morning on 5 March 1966, in Quang Ngai Province, South Vietnam.

Larry and I were hospital corpsmen for 3rd Platoon, Lima Company, 3/1, and our platoon was fighting for its life against combined elements of the 36th Infantry Regiment of the Peoples’ Vietnam Army and Viet Cong Main Force soldiers. Minutes before, as we approached Hill 50 in Quang Ngai Province, South Vietnam, we had been ambushed by a hail of plunging rifle and machine gun fire from above and enfilading fire from our flanks. 1 At least five Marines had been wounded within the first minute or two, some fatally. By the end of the battle, three long hours later, 10 Lima Company Marines were dead, and 20 wounded.

It was a long time before Larry could get to me. In fact, no one could move on that hill safely. I had been about to work on a grievously wounded Marine when I was shot — without immediate first aid, he would surely die from a ghastly abdominal wound. Two other Marines who worked their way up to us to help were also wounded.

I remember trying to give myself morphine, but I forgot to puncture the seal on the syrette, the tube of which burst in my hand when I squeezed it. I don’t recall whether I had another syrette, but by that time I was too weak to try again.

Remarkably, I was not in unendurable pain, and Larry did not give me any morphine. He did apply a battle dressing. I remember that he talked with me, in the midst of battle, about mundane things. I learned that although he was from Illinois, he had married a girl from my hometown, Silver City, New Mexico.

Larry and three Marines eventually half-dragged, half-carried me down the hill on my poncho — they had to stay low because bullets were still flying. Several times my butt bounced on the ground, and I could feel the pieces of the shattered femur grinding together; that was the only time that I suffered pain, and it was severe, but mercifully brief.

While we were waiting for medevac choppers to arrive, Larry and I and other Marines talked. One Marine was in tears; he had just seen his best friend killed. I asked Larry to take a picture of me with my camera, and I took one of him.

My wound was not life threatening, at least not immediately, and I would probably have survived even without Larry’s intervention. However, he offered something just as important as medical treatment: he was calm and self-confident, and seemed unconcerned that he himself could be wounded or killed at any moment. He helped me to concentrate not on my wound, but on the fact that I was alive and headed for safety. He simply ignored the hailstorm of rifle and machine gun fire and grenade explosions that were shredding our company and the Vietnamese soldiers.

Despite Larry’s calm demeanour and my relative lack of pain, Larry and I knew, of course, that I had been severely wounded. My femur had been shattered, and the muscles of my inner thigh had been pulverized. My entire body was, for want of a better word, vibrating. The muscles in both of my legs were contracting and giving me the worst charlie horses I have ever experienced. I was sweating buckets. Without prompt surgical and medical care, amputation or even death were distinct possibilities. But Larry played the vital role of easing my anxiety. In that alone he quietly proved himself to be a thorough and professional Fleet Marine Force hospital corpsman of the highest order. A psychologist in Vancouver, Janice Stuart, confirmed for me that Larry’s calm demeanour in the midst of combat was probably more significant therapy than bandages and morphine, and without doubt helped to reduce psychological wounding.

It was almost 43 years before I had any more contact with Larry. When the initial version of this web page was publshed a few years ago, it contained a plea for anyone who knew Larry to help me contact him, because I wanted to say just two words to him: “Thank you.” However, it seemed that he had disappeared and I never woud get to say those words. Then, on 21 September 21, 2008, I received this e-mail:

We were recently searching for our grandfather that we never had met…. we googled his name and came up on your web page. We found him and let him know that we were not the only ones looking for him. He asked us to give you his e-mail address…. I hope we have been some help to you.

Larry’s grandchildren did indeed help. Subsequent contacts with Larry, by e-mail and telephone, melted away the years, and I have finally been able to tell him how important he was to me on what was arguably the worst day of my life. In turn, I have learned many more details about Larry’s life and military career, and how profoundly his experiences there have affected his life.

-

An infantry unit that is moving ahead on rising ground is vulnerable to plunging enemy fire from above, and to enfilading and flanking fire from the front and sides. In the situation my company found itself in, the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong were well dug in on the hillside, which itself was covered by dense brush. They obviously had clear fields of fire, and we couldn’t see where it was coming from. See Corpsman Down for my detailed account of the Battle for Hill 50. ↩︎