Remembering Fort Bayard, New Mexico — A long walk in the hot sun for an ice-cold chocolate soda

When my family moved to southwestern New Mexico from New York State in 1949, our first home was in the small village of Arenas Valley, about six miles east of Silver City. Arenas Valley for me was a young boy’s paradise, for reasons I explain in my Remembering Arenas Valley web page. But a nearby community, Fort Bayard always beckoned my friends and me.

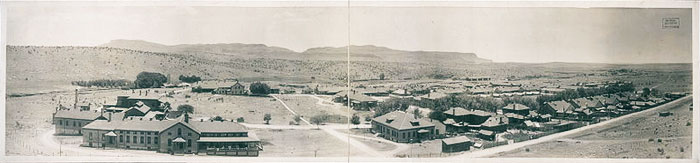

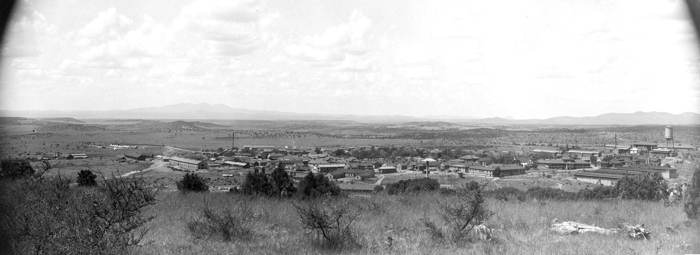

A desert oasis

Arenas Valley was as dry as a bone (Arenas means sand in Spanish). Fort Bayard was lush and green by comparison. Federal dollars and deep wells ensured that its lawns and shrubs were well watered; in Arenas Valley, our own shallow well often ran dry.

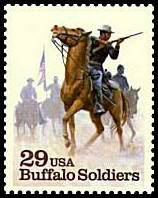

During the Indian Wars that followed the Civil War, Geronimo and other “renegade” Apaches terrorized local settlers, and the settlers and the U.S. Army terrorized the Indians. Fort Bayard at that time was a U.S. Cavalry fort, one of many military bases in the Southwest where units of the the famous Buffalo Soldiers were garrisoned.

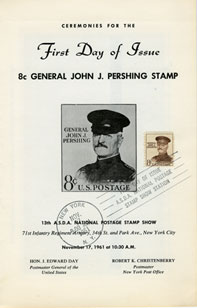

Among the notable individual soldiers stationed at Fort George was John J. “Black Jack” Pershing. In 1886, following graduation from West Point, Pershing was assigned 6th U.S. Cavalry stationed at Fort Bayard. Pershing participated in several Indian campaigns and was cited for bravery for actions against the Apaches. He also Pershing in significant actions in Cuba in the Spanish American War and in the Philippines during the Philippines Insurrection.

In 1916, He commanded what became known as the “Pershing Punitive Expedition” against the Mexican revolutionary bandit Pancho Villa. In March of that year, Villa’s Division of the North raided Columbus, New Mexico, inflicting casualties on civilians and a U.S. Army garrison stationed there. The attack so angered Americans that President Woodrow Wilson ordered the invasion of Mexico in an unsuccessful attempt to capture General Villa.1

At the old Fort Bayard shooting range, we kids sometimes found old spent cartridges and deformed lead bullets. When I was growing up, though, Fort Bayard was no longer a fort as such, but a small community surrounding and supporting a large Veterans Administration sanatarium for soldiers who had contracted tuberculosis on active service.

Fort Bayard was similar to nearby, self-contained “company towns” such as Santa Rita and Hurley. The complex of hospital buildings was surrounded by many other buildings for staff Physicians and senior administrator’s lived in “Doctors’ Row,” which consisted of several large, white houses for the physicians and their families. Support staff and their families lived in other rows of smaller white houses.

Fort Bayard had a post office, a movie theatre, and the Canteen, which sold mostly snacks, magazines, and toiletries. There was no school or church, although there was a chapel for the patients. Kids from Fort Bayard attended schools and churches in Silver City and Bayard; my first date, when I turned 12 (I was a precocious kid!), was with a classmate, Carolyn Hibbard, whose father was Fort Bayard’s chief medical officer. Carolyn hosted at least one party in her large home in Fort Bayard.

I join the Boy Scouts

When a Boy Scout troop was formed at Fort Bayard in the mid-1950’s, I joined up with several other kids from Arenas Valley. We were the “Coyotes,” and met for meetings at Fort Bayard’s Sojourners Club.2 We sang our troop song to the melody of the U.S. Army “Caissons Song”: “Over hill, over dale, / We have hit the dusty trail, / And the Coyotes go marching along.”

It was at Fort Bayard that I passed the test for my Boy Scout stamp-collecting merit badge. The test was administered by the Fort Bayard postmaster; for the occasion, I was allowed to go behind the wrought-iron wickets and into the inner sanctum. After passing the oral test with flying colours, and being complimented on my knowledge of philately, I enjoyed a brief tour of the post office. I remember the postmaster pulling out a drawer and seeing a partial sheet of the special delivery stamp issue of 1951, listed in the Scott Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps as E19. The Fort Bayard Post Office, which opened in 1867, lasted almost a century, closing in 1965.

Fort Bayard didn’t generate a great deal of mail, so covers from Fort Bayard are uncommon. Below is one of the covers in my collection. Although the cost of the pre-stamped envelope included the five-cent rate for airmail postage, it couldn’t have completed the first leg of its trip to Ohio by air: Fort Bayard and other communities in Grant County wouldn’t enjoy airmail service until the Silver City-Grant County Airport opened November 30, 1951.

!!! IMG FILE '/Users/Bob/Sites/ephemeral/html/imgs/fort-bayard-airmail-cover.jpg' NOT FOUND !!!Like an emerald

Fort Bayard was like a gem — an emerald, perhaps — in the rough brown setting of southwestern New Mexico. The buildings always seemed freshly painted, the streets and sidewalks swept clean, the grass freshly trimmed and watered, the trees carefully pruned. Even the TB patients who wandered about in government-issue green pajamas seemed especially tidy and orderly. On a hot day, Fort Bayard always seemed cooler than Arenas Valley, and it might well have been.

It was easy for us kids to get to Fort Bayard from Arenas Valley, as long as we were willing to walk. It was only about two miles away as the crow flies, almost three miles by road.

Sometimes we rode our bikes along the little-used asphalt road that connected the two communities and ran through the protected wildlife area that we called the “Reservation” or simply “Reserve”. That bike ride was spiced by Snake Hill, a serpentine section of roadway that dropped steeply into a valley through which ran a seasonal stream of clear water. The drawback was, of course, that we had to pump our bikes up the other side, and this before the days of 10-speed bikes. (Sometimes, Snake Hill itself was our destination, and we would make the run two or three times just for the thrill of the speed and the wind in our faces.) Snake Hill seemed to belong to us Arenas Valley kids. I recall seeing Fort Bayard kids there only once. And why would they bother? People who live in an oasis don’t visit the desert for fun.

Over hill, over dale…

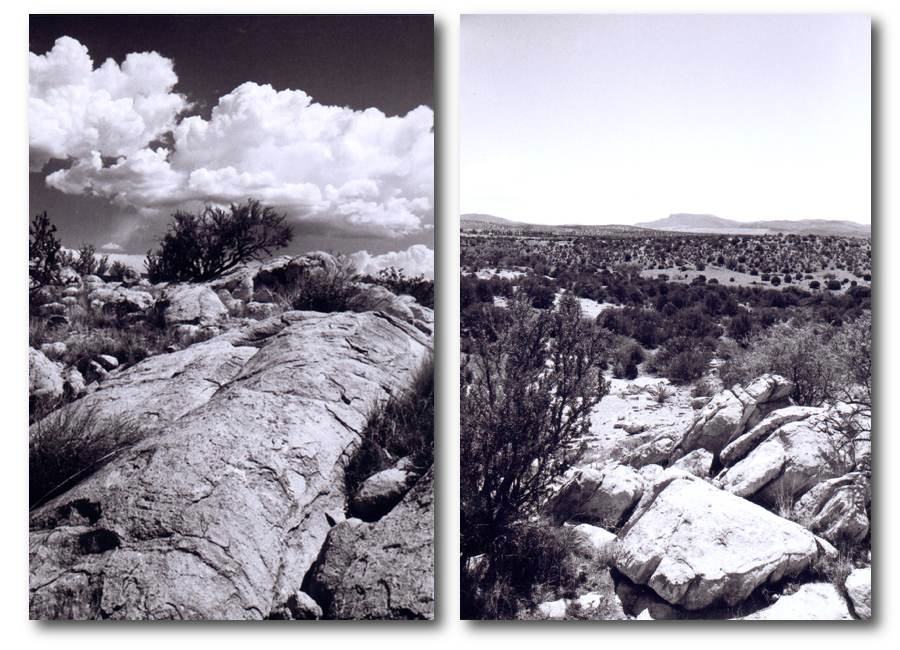

Sometimes we walked to Fort Bayard. We were used to walking, and intimately knew every square yard of our greater neighbourhood. It was nothing for us to fill our army surplus canteens, get our mothers to make sandwiches for us, and set off for a day of exploring, sometimes north into the foothills of the Pinos Altos Range, or eastward into the arid Reservation, where we would sometimes see the small resident herd of pronghorn and would often encounter jackrabbits, cottontails, horned lizards (in those innocent days we called them “horny toads”), bull snakes, lizards, buzzards, and hawks. Sometimes we saw eagles and owls.

A perfect chocolate soda

Once during a long summer school holiday, it was so hot — into the high 90’s, for sure — that my friends and I decided we would walk to Fort Bayard to buy a chocolate soda at the Canteen.

I don’t remember who our group included. Ernest and James Harper, probably, and maybe Danny Sanders. The walk seemed longer and hotter than usual, so we were relieved when we finally trudged on burning feet past the rows upon rows of white tombstones in the cemetery (a great many of Fort Bayard’s TB patients succumbed to their disease over the years).

The Fort Bayard cemetery is hallowed ground in a personal sense: My sister, Helen Francis, who has long been interested in genealogy, learned only a few years ago that one of our distant relatives, David Lusty, is buried there. My friends and I used to walk very near his grave, but had no idea he had ever existed.

As a young man, David went off to the Philippines to fight with Company I, 5th U.S. Infantry, in the the little-known Philippine Insurrection — and contracted tuberculosis. He was sent back to the States, to Fort Bayard, where he died on May 13, 1902.

Tuberculosis was one of the leading causes of death in the United States in the early twentieth century. Those infected with tuberculosis were isolated from society and placed in sanatoriums, known as "waiting rooms for death," and half the people who were diagnosed with TB died within five years.3

Once we had passed the cemetery, we walked past the Sojourners’ Club, and down the hill and into the cool quonset-hut interior of the Canteen.

In the 1950s, Fort Bayard seemed very much a military hospital, with manicured grass and shrubs and white buildings. The Canteen, more military than civilian, more utilitarian than commercial, was more for the patients and the employees of the hospital than for us, but we were made welcome.

I don’t remember who served us, or the cost, but I do remember — how could I possibly forget? — the rich chocolate soda in a classic, tall soda glass, served with a straw and a long-handled steel spoon.

On that day, my concept of the perfect chocolate soda was firmly fixed in my mind: never before had a chocolate soda been so convincingly chocolate, so chillingly frosty, so smoothly delicious. I haven’t had one quite so good since then! (What happened to chocolate sodas? To drugstore soda counters? To “soda jerks”? Is the world a better place because we no longer can enjoy drug store chocolate sodas?)

In 1965, the State of New Mexico took over Fort Bayard and began operating it as a hospital for permanently disabled patients. My paternal grandmother, Ratie Ingraham, lived there for several years until her death in 1985. Until 2010, it was long-term care center for military veterans. When I was last there, in 1999, its grounds and buildings were showing clear signs of age and neglect. The quonset hut used for the canteen was still there, but certainly not in use.

In July, 2002, the Fort Bayard National Cemetery was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 2004, the Fort Bayard National Historic Landmark Act was signed by the president, but it allowed only for co-operation between New Mexico and the federal government “to protect historic resources at Fort Bayard and to provide educational and interpretive facilities and programs for the public.” However, there was no co-operation between the state and federal governments. The buildings and grounds were not protected, and no education and interpretive facilities were developed. Then, in 2012, New Mexico’s Military and Veterans' Affairs Committee voted to demolish what remained of Fort Bayard to pave the way for “economic development”.

In an email sent in February, 2014, Silver City resident Mark Erickson noted that since the state hospital was relocated, old Fort Bayard was slowly disintegrating:

Even though it has a National Historic Site designation, the state will not allow any work done at all. The physical plant workers try to at least keep the grass mowed, but the buildings are in deplorable shape with vandals breaking out windows and gang grafitti is on many interior walls. I noticed the other day that the bronze cornerstone on the hospital had been stolen.

The Fort Bayard Historic Preservation Society attempted to slow or even stop the destruction of Fort Bayard, but failed. On August 25, 2015, the Grant County Beat blog reported that a contract has been awarded for the demolition of the main hospital building: The old Fort Bayard Medical Center building will soon begin tumbling down

Despite the efforts of activists to preserve the historic buildings and grounds of Fort Bayard, bulldozers moved in and within a few months only the cemetery and a memorial to the Buffalo Soldiers remained.

Arenas Valley, too, has fallen on hard times. Weeds grow where once there were gardens and orchards. Fences sag and houses peel. House trailers have sprouted like invasive weeds. The post office has been closed for years, and even the road between Arenas Valley and Fort Bayard is gone. There may be a few children living in Arenas Valley, but I doubt that they ever walk across the Reserve to see what little remains of Fort Bayard. Why would they bother, without the pleasure of an ice-cold chocolate soda at the end of the long, hot hike?

Suggested reading:

Remembering Arenas Valley / Box 28 — Arenas Valley

-

The Punitive Expedition had some positive results: For the first time, an aircraft, a Curtis JN3 from the 1st Aero Squadron was used in combat, in an aerial reconnaissance role. Additionally, Pershing, aware that mounted cavalry soldiers would be at a severe disadvantage in a future war, which would see the first widespread use of machine guns and aircraft, used the expedition as an opportunity to train his men — who were reluctant to dismount their horses — as foot soldiers. That training no doubt helped to keep many of them alive when, still under General Pershing, they joined the Allied Powers (Great Britain, France, Russia and Italy) in their fight against the Central Powers (Germany, the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria). ↩︎

-

The Soujourners Club was built by New Mexico’s Masons in 1923 to serve the needs of Fort Bayard’s patients. The Masons invited General Pershing, invited by the Masons to attend the opening of the Sojourners Club, struck a gold nail in the building’s cornerstone. ↩︎

-

Tuberculosis and the Ingraham Family: Both sides of my family were deeply rooted in New York State, but in the 1930s my grandmother, Ratie Ingraham, was diagnosed with TB. (Ratie really was her name; it was pronounced RAY-tee.) After several years, when it became clear that she was not getting better despite long stays at Mount Morris Tuberculosis Hospital in New York, a friend suggested that she move to the Southwest, long a haven for tuberculars. She and my grandfather moved to Silver City, in 1945; my grandfather soon got work as a machinist at the Kennecott copper smelter in Hurley. The move apparently cured my grandmother’s TB; she died at age 95 of the complications of old age and terminal irritability. ↩︎