Remembering Arenas Valley, New Mexico — We played with the ghosts of Geronimo and Billy the Kid

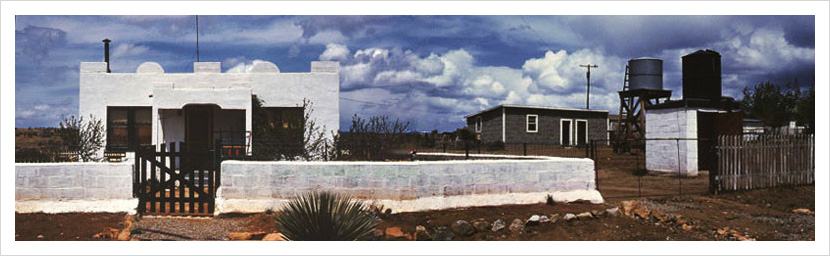

When I was six years old, my family moved from the small village of Savona in western New York State to the even smaller village of Arenas Valley in Southwestern New Mexico. It consisted of a few-score houses clustered around a tiny post office, six miles east of Silver City and two miles west of Fort Bayard.

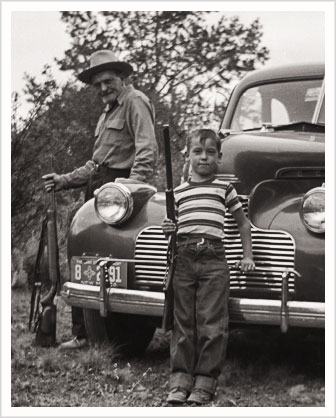

At age six, I was ready to let go of Mom’s apron strings and start exploring my new world. I soon met Ernest Harper, whose mom was postmaster, and became part of his circle, which included his brothers, Ira and James, and Danny Sanders, and sometimes Scotty Calloway, and other boys whose names I no longer recall. We did not include my sister, Helen, who was four years older than me. A special treat included hunting trips (for rabbits) with my Grandfather Ingraham.

Our “hobby farm”

We lived in a small, white house that my grandparents had bought for their retirement (their home was in the company-owned town of Hurley, about eight miles to the south, where my grandfather worked in the Kennecott copper smelter). It was on a lot about half an acre in size which had once been — we were told — the location of a small dairy. One outbuilding, which the “bunkhouse,” had been used at some point to house livestock, perhaps three or four milk cows or and perhaps even a cowboy or two.

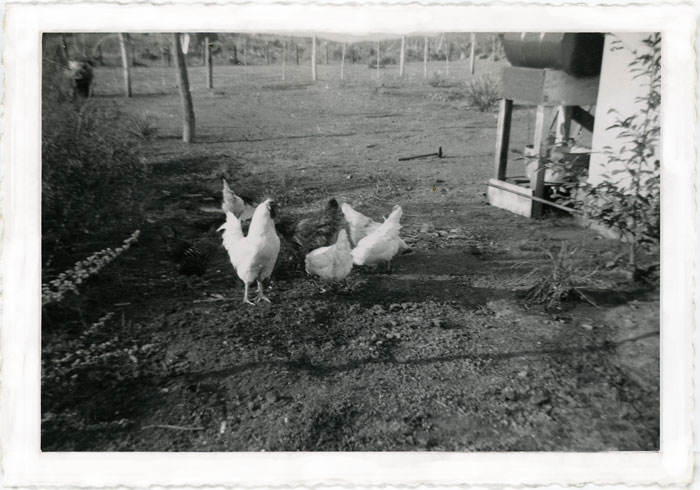

Today, our place would be called a hobby farm: we had chickens (including two pets, a Rhode Island Red hen, Lucy, and a Leghorn rooster named George), bantam chickens (Chinese Silkies and a Black Cochin who died of a brain tumor), rabbits, horses, white rats, and once a stray donkey.

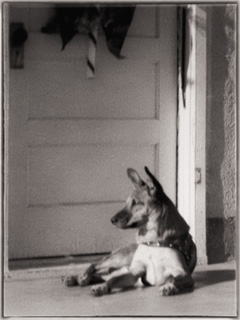

We had various dogs; the house came with a very pregnant bitch who had 13 puppies a few days after we moved in, and cats whose life spans were all too brief: they seemed obsessed with crossing the road just in front of our house just when cars or trucks were approaching.

At times I briefly held captive local bullsnakes, horned lizards (which we innocently called “horny toads”). My family adopted a baby jackrabbit and raised him to plump and very un-domesticated adulthood before releasing him into the prairie in back of our house. He probably provided dinner for a hungry coyote that same day.

Artifacts and wilderness

Just beyond the fence on the north side of our property there had been an Amerindian village, probably occupied more than 1,200 years previously by a sub-group of the Anasazi culture called Mimbreños. Despite years of pillaging for artifacts, the remains of a few circular “pit houses” could still be seen. In my own backyard, I often found shards of Anasazi pottery painted in intricate geometric designs. Once, after a thunderstorm, I found a white stone arrowhead. The arrowhead went missing long ago, but I still have one of the pottery shards.

Behind our house, spanning the horizon from northwest to east, were the mountains and ridges and canyons of the Gila National Forest, which includes the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Area, established in 1928. It would have been possible — but foolhardy — for me to walk out the back door of our house and north into a wilderness which extended more than 160km (100 miles) into the Gila National Forest and then the Gila Wilderness Area. But my friends and I spent long days exploring into the foothills of the Piños Altos Mountains, never encountering another soul. As far as I know, there was only one family living well north of the “built-up” area of Arenas Valley and the mountains; their surname was Elias, and had two school-age kids, but I never got to know them or anything about them.

Arenas Valley offered not only hiking, but a lot of other unscheduled recreation for my rowdy friends and me. When we weren’t in school, we spent much of our time trying to murder sparrows with our BB guns, impaling beetles on cactus spines, blasting tomato cans and ant hills apart with “cherry bombs” and M-80 firecrackers, and brandishing potentially-lethal spears made from yucca stalks tipped with six-inch spikes that we hammered flat and filed to near-razor sharpness. We made “rockets” by wrapping the heads of wooden matches in aluminum foil and heating them to ignition with other matches. Once we took apart two or three 30-30 rifle cartridges, packed the powder from all three into one cartridge case, hammered the bullet back into the case, and then heated the case with matches until the powder detonated impressively — and dangerously!

In the summer, during our a three-month school holiday, we camped out a lot, usually in the Harper’s back lot. I well remember the camaraderie we enjoyed around roaring campfires that incredibly dark, starry New Mexico sky. We slept in sleeping bags in U.S. Army surplus pup tents; my mom fashioned my sleeping bags from a couple of warm blankets fastened with giant horse-blanket safety pins. When we awoke, we would crawl into the chilly dawn to dress — unforgettably! — in cold, stiff Levis, warm ourselves at the fire that James Harper would build for us, and dig into breakfast, in this order: crisp bacon, then fresh eggs fried in bacon grease, then bread fried in bacon grease and slathered with strawberry jam. We washed everything down with water from U.S. Army surplus canteens.

Sometimes we were “walk-in” patrons of the Copper Drive-In theatre, a mile or so away from our village on Highway 180. We’d get there about dusk, and sit on blankets in the front row. The manager indulged us (we didn’t have to pay, but we’d buy treats at the snack bar). After the films we’d fumble our way “home” to our pup tents in the dark, lighting our way with flashlights, sometimes blundering into cactuses and once surprising a jackrabbit who burst out of his hideyhole and scared us more than we scared him.

Youthful dramatics

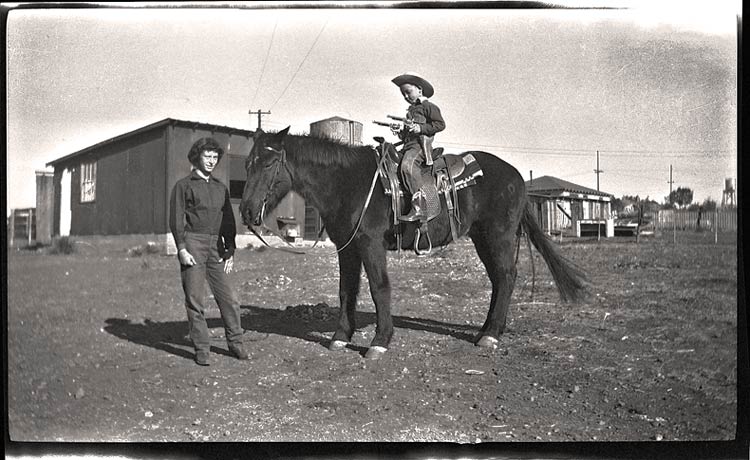

During the day, we often staged elaborate scenarios involving “Cowboys” and “Indians” or “Good Guys” and “Bad Guys” — I’m sorry to say that “Indians” never took the role of Good Guys; it was heyday of the Hollywood Western, and Indians rarely got the better of the Good Guys. And the on-screen “Indians” were always white actors.

My favourite sidearms in this play were a pair of toy cap guns: matched, full-scale, white-handled Colt .45s. Sometimes, one of us would take on the role of the desperado Billy the Kid, who had actually been a kid like us, 70 years before, in nearby Silver City. Or one of us might play the role of Sheriff Pat Garrett, who in July, 1881 tracked down and killed Billy the Kid.

We weren’t fussy about historical accuracy: “Billy” gunned down “Pat” at least as often as “Pat” ambushed “Billy.” And, of course, the imaginary bullets caused no pain, and our heroic “deaths” were immediately followed by miraculous “resurrections”.

Boyhood heroes

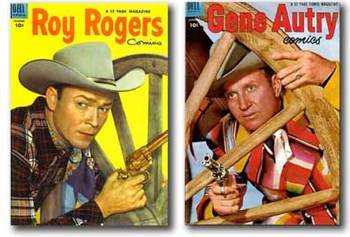

We were partial to two famous stars of the “Westerns,” Roy Rogers and the singing cowboy, Gene Autry, and devoured every new issue of their comic books, two covers of which are pictured at the right. I preferred being “Roy,” but I could assuming the role of “Gene,” if I had to (in other words, if someone else “got dibs” first!)

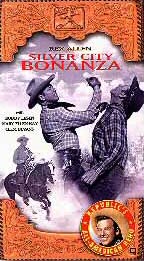

Roy lost my allegiance for a time when another singing cowboy, Rex Allen, visited Silver City in person, probably to promote his 1951 film, Silver City Bonanza, which is set in Silver City, Arizona (despite the fact that there is no Silver City, Arizona!), and was filmed at two locations in California.

I doubt that Rex could ever have beaten Roy, or Gene, or even Billy the Kid in a fast-draw contest, because he crossed his arms to draw, grabbing the pistol on his left hip with his right hand, and vice versa. I didn’t question it then, but it seems to me now that such a fancy move in a real gunfight would have guaranteed the gunfighter a short trip to Boot Hill. It is simply unergonomic! Anyway, I started wearing my own toy Colts backwards too, and became adept at my own “Rex Allen fast draw,” at least in my mind. Could I have outgunned Billy the Kid? You bet, pardner!

We weren’t always just playing games…

Our games weren’t always just games. By age 10 or so, I had my own .22 rifle and, with my parents’ permission, often went target shooting or rabbit hunting. A box of 50 long-rifle cartridges cost...50 cents!1

My friends and I might have seemed typecast for William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, but we weren’t completely without redeeming qualities: we often sought more civilized pursuits in neighboring Fort Bayard. I discuss that interesting community in another web page, Remembering Fort Bayard, New Mexico.

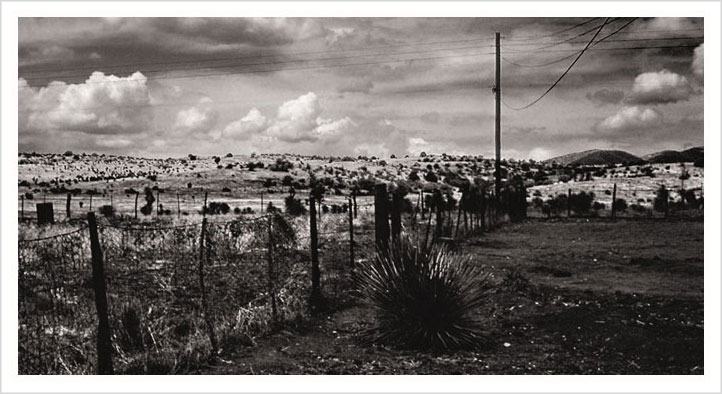

Arenas Valley has long since fallen on hard times, and no longer looks like the community it once was. Weeds grow where once there were gardens and orchards. Fences sag and paint peels, and house trailers sprout like invasive weeds where once there were just yuccas, jackrabbits, and the occasional gopher. One wonders if it’s a community at all.

Suggested reading:

Hiking to Fort Bayard / Arenas Valley Post Office

-

My blood lust end in my mid-teens when I badly wounded a cottontail rabbit with a “lucky” shot and had to shoot the poor thing again to put it out of its misery, not to mention my own misery! I soon sold my rifle. Several years later, in South Vietnam, I would learn exactly what it’s like to be badly wounded when a communist rifleman shot me through my right thigh, shattering my femur and confirming my suspicion that war is not good for living things! If you’d like details, go to Corpsman Down!, which was published by the March/April, 2007 issue of Navy Medicine, the journal of the U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine. ↩︎