Payday: Cash for Chinese employees at Woodfibre Pulp & Paper Ltd. — Part 3

In 1941, Japanese Canadians faced a bleak future. On December 7 of that year, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. The Canadian government immediately declared war on Japan and passed an order-in-council identifying Japanese Canadians, including those born in Canada, as “enemy aliens”.

In March, 1942, an estimated 22,000 Japanese Canadians living and working in British Columbia were ordered to leave their homes and report for transportation to internment camps in BC’s interior, east of a quarantine zone that extended 100 miles from the Pacific coast. Many were moved into the Okanagan region of in southern BC or Alberta to work as agricultural labourers. (Japanese in several other provinces were also interned.)

The Canadian government shut down all Japanese-language newspapers, took possession of businesses, fishing boats, vehicles, houses and personal belongings — and sold them. In effect, interned Japanese were prisoners of war; some middle- and upper-class families who were not deemed to represent a security risk were placed in euphemistically named "self-supporting projects" (also called "relocation centres"); they were legally allowed to leave the camps, if granted permission to do so, but since they weren’t allowed to work outside the camps or attend school the great majority elected to remain in the camps (some of which had to built from the ground up by the internees themselves.

It was risky for internees to complain too loudly. Some 700 “complainees” found themselves imprisoned in POW camps in Ontario for the duration of the war.

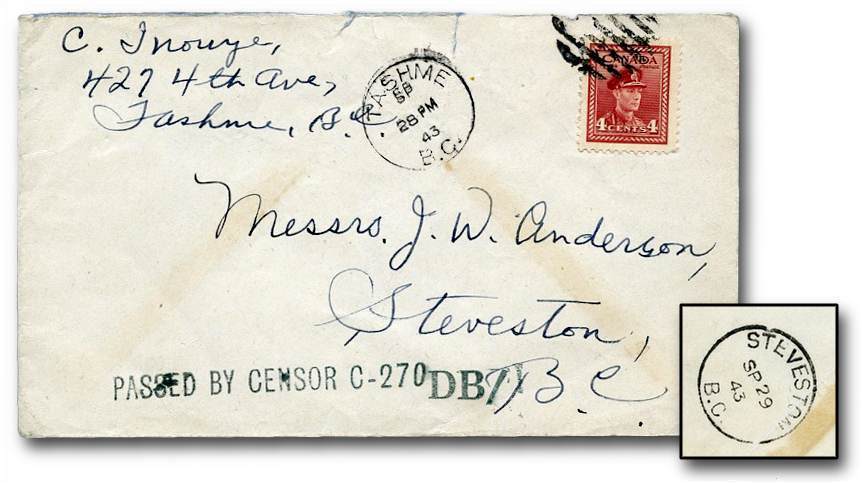

One of the largest camps, with 2,400 Japanese-Canadian internees, was Tashme, southeast of Hope, BC on the Crowsnest Highway near the entrance to Manning Park in the Cascade Mountains, and about 155 km east of Vancouver.

Following internment, internees returned and re-established their community. The seven-year internment lasted until March, 1949, when Japanese Canadians were given the right to vote in provincial elections, after receiving voting rights for federal elections in 1948). Ten thousand Japanese Canadians, some of whom were born in Canada, were deported to Japan.

What a pointless exercise! In effect, the internment utterly destroyed a blameless and hardworking cultural community that had done its best to become a part of Canada.

In the years following the internment, “Little Tokyo” in East Vancouver (also known at times as “Little Yokohama” and “Japantown”) began to devolve into an urban slum inhabited today by a rough mix of prostitutes, homeless street people, and drug addicts. As of this writing, in October, 2014, the city government was arguing in BC Supreme Court that it had the right to remove to poverty and aboriginal activists from Oppenheimer Park in the heart of Little Tokyo and immediately north of Chinatown. The activists first set up a camp in Oppenheimer to protest what the squalid living conditions in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

Ironically, the heavy-handed treatment of Japanese Canadians, not to mention the war itself, conferred a blessing of sorts upon Chinese Canadians. At least they no longer had the Japanese Canadians to compete with! The Republic of China was, nominally at least, an Allied nation, so Chinese Canadians were, sort of, allies in the war against the Axis. More importantly, for British Columbia’s forest industries, they represented a source of labour to replace the Japanese employees who had all been interned.