PAYDAY AT WOODFIBRE (Part 1) — A bag of cash for Chinese workers at a BC pulp and paper mill

Editor’s Note: It’s difficult to obtain information about living and working conditions at Woodfibre, British Columbia in the 1930s, 1940s, or 1950s, especially for Chinese employees. If you can help, please contact me at [email protected] or call 604-694-0014.

On April 10, 1946, the Bank of Nova Scotia in Vancouver posted a bag of money1 — literally! — to the British Columbia Pulp & Paper Company at the small town of Woodfibre, 48 km (30 miles) north of Vancouver on the mountainous northwest shore of Howe Sound. The notation “CHINESE PAYROLL” on the shipping tag, struck through and then rewritten — raises questions that so far defy answers, and reveals a century of Canadian racism no less dark than that of South African apartheid and elements of the Holocaust.

!!! IMG FILE '/Users/Bob/Sites/ephemeral/html/imgs/woodfibre-tag-front-back-detail-no-lines.jpg' NOT FOUND !!!Until January, 2006 Woodfibre was the location of one of several pulp and paper mills in B.C., which in modern times has based its economy in large part on forestry.

Beginnings

The story of Woodfibre dates from the early 1900s when a small sawmill was built in the area known as Mill Creek. The sawmill’s operators and employees weren’t the first residents of the area, which had been known as Swig’a’t (pronounced Sway Ott) by the aboriginal peoples of the Squamish First Nation.

Like other resource-based communities in B.C., Woodfibre was isolated by geography. The nearest community, Squamish, eight km east-northeast of Woodfibre at the head of Howe Sound, was accessible only by water. Vancouver lies 48 km to the south.

In 1910 or 1911, the British Columbia Sulphite Fibre Company Ltd. began construction of B.C.’s third pulp mill on the site; workers, some of whom had to pay a dollar to be accepted for employment, were transported by boat from Vancouver and lived in bunkhouses built by the company while the mill itself was under construction. The mill began to produce pulp in 1912.

From its beginning and throughout its operational life, pulp wood for the Woodfibre mill came primarily from the Island and further north on the BC coast where the owners had timber tenure. In the 1920s, Cedar Creek Logging Co., located on the Woodfibre site, operated independently and but sold some of its pulp wood to the mill while marketing most of its log production elsewhere.

By 1917, ownership passed to Whalen Pulp and Paper Co., whose principals had been involved in the Woodfibre project from the beginning. As more workers were hired and families joined them, the company began to develop a formal townsite. Rows of white frame homes began to climb up the mountainside. The complex, which at times included a shingle mill, obtained water from sources high in the mountains above.

In 1921, Mill Creek needed a post office. Postal officials apparently decreed that a town required a unique name if it was to have a post office. Since another post office in B.C. was already called Mill Creek, a contest was held to find a new name. Local resident Cathy Haar won $50 for her suggestion, “Woodfibre”.

Over the coming decades, the Woodfibre pulp mill would be owned by several companies and go through several upgrades to take advantage of newer pulping technologies. This timeline provides a brief summary of Woodfibre’s corporate history.

By 1945, there were only five pulp mills on the B.C. coast (or just three, according to another source), and none in the interior. Like Woodfibre, the other coastal mills were accessible only by water. In terms of electricity, the mills were self-supporting: there was no province-wide power grid.

According to the BC Business web site, by 1954 Woodfibre was a “lively” town with two churches, a school, a swimming pool, and a bowling alley for the mill’s 750 workers and their families. They could also go to the movies: cartoons and films were shown for children at the community hall on Saturday mornings; adults could see movies in the evening at the Canadian Legion.

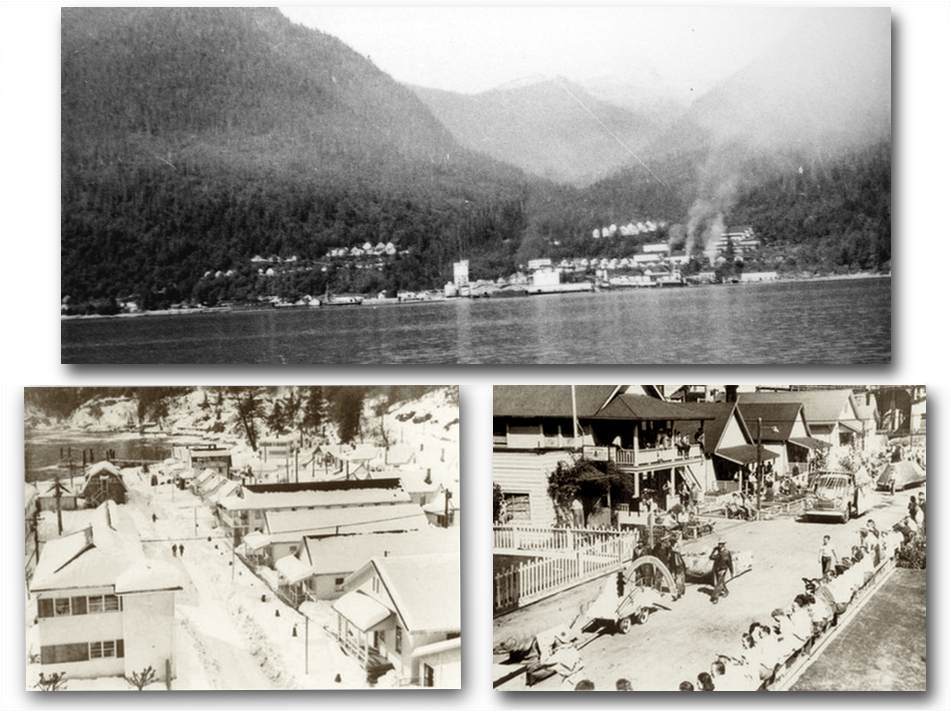

Photographs archived by the Squamish, B.C. public library show a May Day parade in the 1950s, local homes and streets, as well as buildings which appear to be dormitories. A photograph in the collection of the Vancouver archives, taken from Howe Sound, shows the pulp and paper mill, homes, and, again, buildings that appear to be dormitories.

Life was not uniformly good at Woodfibre. In 1955, for example, an underwater slide carried pilings out from under the dock and caused warehouses to collapse, resulting in the loss of 400 tons of pulp and five forklifts. On August 18, 1963, a wood-pulp boiler exploded, killing seven men and putting 300 men out of work. Also in 1963, floodwaters pouring down from Mount Sedgwick, north of Woodfibre, engulfed both the townsite and pulp and paper mill.

Photographs and written records about Woodfibre rarely describe what life was like for one group of workers — Chinese immigrant labourers, who, until 1947, were not and could not become Canadian citizens. Only as a result of the Second World War did Chinese immigrants gain a toehold in BC’s forest industries.

Next, in Part 2: In the mid-19th Century, thousands of Chinese come to Canada in search of gold. Later in the century, thousands more emigrate to work on the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railroad; many are killed in accidents or die of disease and malnutrition. Punitive tax legislation in the form of the “head tax” prevents Chinese men from bringing their families to Canada and inadvertently creates a “community of “bachelors”. Discrimination prevents Chinese from working in any but menial jobs.

-

Money was commonly sent by mail through the mid-20th Century, and workers were often paid in cash. In the 19th Century, it was common to identify mail that included money with a handstamp reading “MONEY LETTER”. ↩︎