PAYDAY AT WOODFIBRE (Part 3) — In the years before WWII, BC’s forest industry imposes harsh discrimination against Asian workers

Like the rest of British Columbia’s industries, owned and operated almost exclusively by white Canadians, the province’s forest industries had always engaged in ill-concealed discrimination against Chinese and Asians generally. But they had employed Asians.

In 1935, the forest workforce in BC totalled 23,924, of whom 7% (1,674 employees) were Chinese and 6% (1,435 employees) were Japanese.

Over the next six years, discrimination against Asian forest employees increased. By 1941, employment in BC’s forest sector would drop by more than 35%. In that year, 15,423 employees would be counted as forest employees, but only 3% (442 employees) were Chinese Canadian, and 5.5% (855 employees) were Japanese.1

Pay inequities

Despite the steadily decreasing numbers of Asian employees in forest industries in the early years of the Second World War, employing Asian workers made sense for forest industries in BC, because they paid Asian workers less than white workers doing the same jobs. In Capital and Labour in the British Columbia Forest Industry, 1934-74, Gordon Hak writes about pay inequities between Asians and white workers:

In the spring of 1936, white firemen were paid 45 cents per hour while the one Chinese fireman received 40 cents. White carloaders were paid 40 cents per hour, but Japanese carloaders got only 35 cents. White doggers received 45 cents, while Japanese and Chinese doggers got only 40 cents…. (Dogging was an operation, now obsolete, that consisted of positioning the logs for sawing, using dogs — steel, tooth-like projections on the carriages that moved logs into position for sawing into boards, which in turn were turned into chips for making wood pulp.)

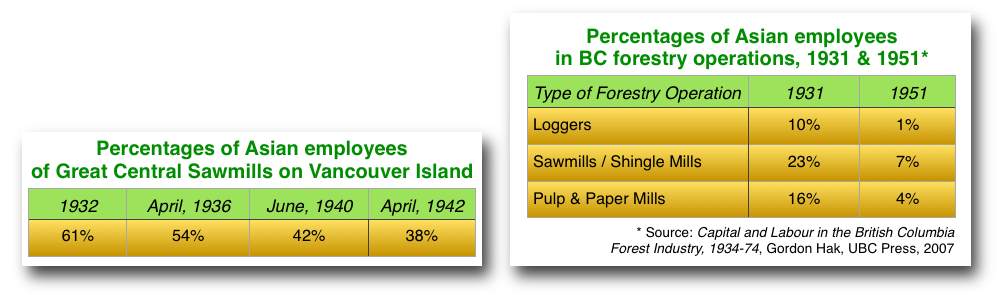

Nevertheless, since the early decades of the 20th Century, BC’s forest industries had made a concerted effort to hire white rather than Asian workers. The table below at the left shows changes in the percentage of Asian employees working at Great Central Sawmills on Vancouver Island in four years between 1932 and 1942; below at the right, the percentage of Asians working in three different forest industries is shown for the years 1931 and 1951:

The steady attrition of BC’s Asian forest workers throughout the first half of the 20th Century reflects the belief of white forest workers that Asians threatened their jobs. They were not silent about their concerns; as a result, forest companies throughout BC had hired increasingly fewer Asian workers.

Labour unions to the rescue (or not)

In 1943, it looked like the International Woodworkers of America (IWA) was on the side of Asian workers. The union needed members, and met with the provincial cabinet, in the company of eight Sikh forest workers, demanding “‘British justice and employment of democratic rights for the East Indian community of British Columbia.’”2

IWA’s “hire Asians” policy, which had been in place since at least 1937, was a hard sell for the union’s rank and file, who reasoned that an Asian employee on the floor represented an unemployed white man. The IWA found a way out of the dilemma at one mill, or so its officials thought: At the same time the union was enrolling Japanese members at Pacific Mills in Ocean Falls, and fighting for pay equity for workers, it secured the agreement of the mill’s owner not to hire any more Japanese workers. Over time, the union believed that natural attrition would lead to an all-white work force. Later, when the company began hiring more Chinese employees, the union was furious.3

Next, in Part 4: Until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese-Canadians were a respected if not fully-integrated part of the workforce in British Columbia's pulp and paper mills. Within four months of the attack, however, they and their families are sent to internment camps in the province's interior, and in some cases to POW camps in eastern Canada.

-

There seems little doubt that the forest industries discriminated against Chinese to a greater degree than Japanese. In the late 1930s, there were twice as many Chinese as Japanese in the province, yet Japanese were twice as successful as the Chinese in obtaining forest jobs. Education and skill seems to have had little to do with the success of the Japanese, since all Asians — who comprised just 5% of British Columbians in 1941 — were relegated to hard labour rather than skilled jobs. ↩︎

-

Quoted from Capital and Labour in the British Columbia Forest Industry, 1934-74, Gordon Hak, UBC Press, 2007. ↩︎

-

Companies that refused to hire Asian workers weakened their position in the marketplace, since higher wages for their white workers meant lower profits at the end of the fiscal year. ↩︎