Christmas tragedy at Prestwick (Part 5)

An extraordinary coincidence

Jim Yates, who now lives in Toronto, was 12 years old at the time of the crash, but does not remember it. However, he sent an e-mail to tell about some extraordinary coincidences regarding the crash at Prestwick. He wrote:

An acquaintance, a keen stamp collector, came into the possession of a crash cover envelope and, since I am a Scot, asked whether I knew anything about the accident.

I was 12 years old at the time and, surprisingly, knew nothing of a major plane crash at Prestwick in 1954. My friend, also Scottish, didn’t have a clue either — this is sort of surprising since Preswick is located just 40 miles or so from our homes in Glasgow.

Anyway, we decided to Google the subject and WHOA, up came your piece about the crash. But that’s not where this all ends.

I mentioned the find to a friend of mine, another Scot who worked for a news agency at the time, and he covered the story of the crash! In fact, before I even mentioned the site, he told me that he took a picture of a teddy bear in the wreckage! He was 20 at the time and this week celebrated his 70th birthday. He was astonished, as we all were.

I do remember the Stratocruisers at Prestwick, and can clearly remember as a child waving off an aunt from Prestwick, en route to New York.

Jim wrote again to tell me of a conversation: “A good friend of mine, Jean Docherty, said she was 14 and living in Manchester when the plane went down. She said she remembers the air of utter gloom which descended on their house when this happened on Christmas morning.”

Margaret Coogan, Stewardess

Another family that was traumatized by the Prestwick crash was that of flight attendant Margaret Coogan, age 28, one of the four G-ALSA crew members who were killed. She was alive when she was pulled from the wreckage but later died.

Margaret wasn’t supposed to have been working that flight. Her nephew, Martin Coogan, who lives in Sutton-in-Ashfield, Nottinghamshire, explained the circumstances in an email: “The story was that she was due to take a break over Christmas and spend it at home with her parents, but after an argument with her father she swapped with a colleague and thus was on the fateful flight.”

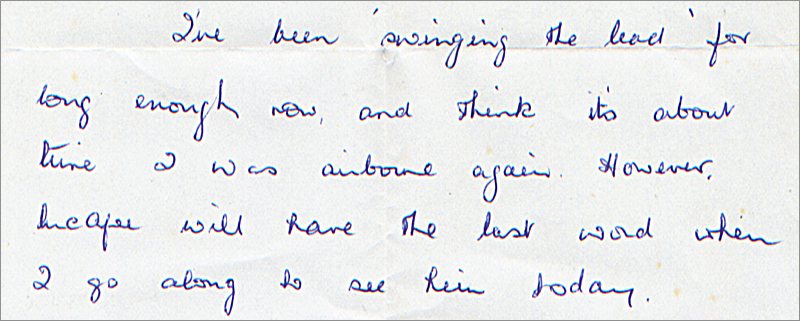

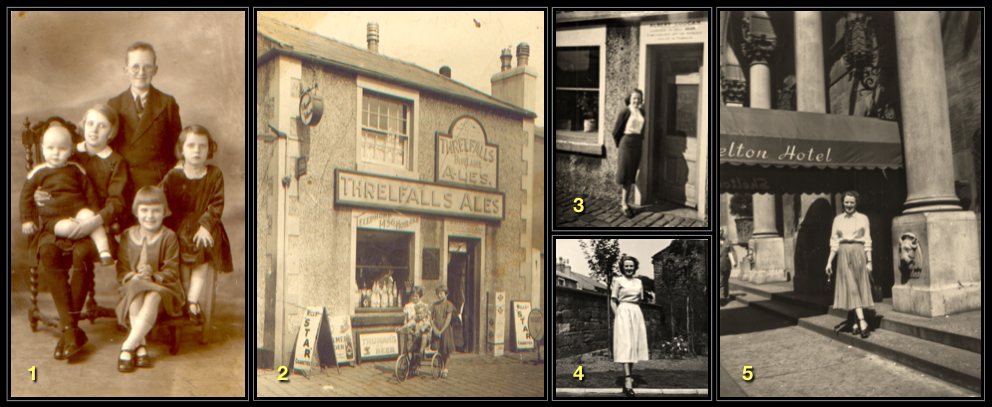

Margaret was the second youngest of five siblings, but her death wasn’t the Coogan family’s first tragedy, or even its second. Margaret’s eldest brother, Edward F. Coogan, known as Teddie, was killed in 1937 in a motorcycle accident on the Wirral Peninsula, across the Mersey from Liverpool. He was about 18. Margaret’s eldest sister, Frances W. Coogan, died in 1943 at age 21 or 22, apparently from an infected blister caused by an ill-fitting shoe. Margaret was survived by her younger brother, Bernard (Martin Coogan’s father) and her older sister, Maureen.

It’s not known how long Margaret had worked for BOAC. In a letter to Bernard, dated October 29, 1951, she said that she was hoping to go back to work, apparently after a voluntary break or, as she put it, “…swinging the lead…”.

Martin, who was born in 1958, wrote that his father never talked about the crash and that his mother only told him about it when he was about 12 years old, some 16 years after the crash, but he remained unaware of the circumstances of the crash until he found this web page.

Martin said that Margaret used to take her brother to the cinema when they were young. “I think that Margaret’s death must have had quite an effect on him,” Martin wrote.

In the cargo — diamonds!

Donald Fraser, who lives in Old Kilpatrick, a few miles west-northwest of Glasgow, wrote to provide the intriguing information that more than £1 million worth of uncut diamonds were thought to have been aboard the aircraft. He said that Scotland’s Daily Record & Sunday Mail and the Glasgow Herald ran stories saying that the diamonds were contained in postal packages along with 250 other bags of mail that were also on board. The post office sent staff who took over the entire Prestwick restaurant/canteen to sort through the recovered mail.

Only about 300 diamonds were recovered, although the authorities removed all the top soil from the crash site as it was thought that the rescue workers may have inadvertently trod on the diamonds, forcing them into the soft earth. All of this was done at the behest of Lloyds, which carried the insurance on the stones.

An airline detective, Donald Fish, was in charge of B.O.A.C. security at Prestwick at the time of the crash. He writes about the diamond incident in his book, Airline Detective (Collins, London, 1962).

Donald Fraser further noted in his e-mail that the story of the crash was in the news from the date of the crash, Dec. 27, 1954, through early January of 1955, but then was pushed off newspaper pages by the march of daily events.

Final Notes

In 1954, flying across the Atlantic in civilian landplanes — as opposed to the giant seaplanes of the 1930s and 1940s — was becoming commonplace. Military transport and bomber pilots — among them Captain William L. Stewart, BOAC Stratocruiser G-ALSA’S pilot at the time of its crash at Prestwick — had pioneered the routes over the course of the war; the first Trans-Atlantic flights by civilian aircraft — most of them converted military planes — took place almost before the sounds of gunfire had faded away in Europe.

These early, post-war flights between Europe and North America were not the non-stop, globe-straddling flights of later years. The big propeller-driven airliners of the 1950s may have been more romantic than today’s jets, and the food and and the service were a lot better, but they weren’t very efficient: they guzzled fuel at prodigious rates and they routinely had to stop to refuel at Prestwick, at Shannon, Ireland, and at Gander, Newfoundland. If it had not crashed at Prestwick, the G-ALSA would probably have followed this same route on its way to New York City.

The Christmas-morning crash at Prestwick was but one of the many disasters that have attended the development of modern commercial aviation. In fact, the Prestwick crash was just one of 19 airliner accidents around the world in that month alone; in addition to the 28 people killed at Prestwick, at least 134 people died in 18 other airliner crashes (records of fatalities are unavailable for some accidents). Fortunately, the introduction of jet engines, far more reliable than piston engines, helped to make airliners the safest mode of transportation in history.