North Star Falling ~ Death rains from the sky over Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan (Part 7)

Recovery of the bodies of the victims of the collision between the TCA North Star and the RCAF Harvard was the top priority, of course, but recovery of mail that was on board placed a close second.

For decades, commercial airlines had depended on government contracts to carry mail, and TCA was no different than other airlines in this respect. Almost 36 kilos (79 lbs) of mail had been on the first leg of Flight 9 from Montreal, and another 454 kilos (1,000 lbs) was picked up in Toronto. However, because an unknown quantity had been loaded at Winnipeg, officials did not know how much mail had been on board the North Star at the time of collision.

Most of the mail involved in the crash ended up in the burned-out basement of the Hume residence. There, during the search for the mail, charred human remains were found; dentures recovered were confirmed as belonging to housekeeper Martha Hadwen, the only Moose Jaw resident who became a victim of the North Star-Harvard collision.

In the midst of chaos, organization

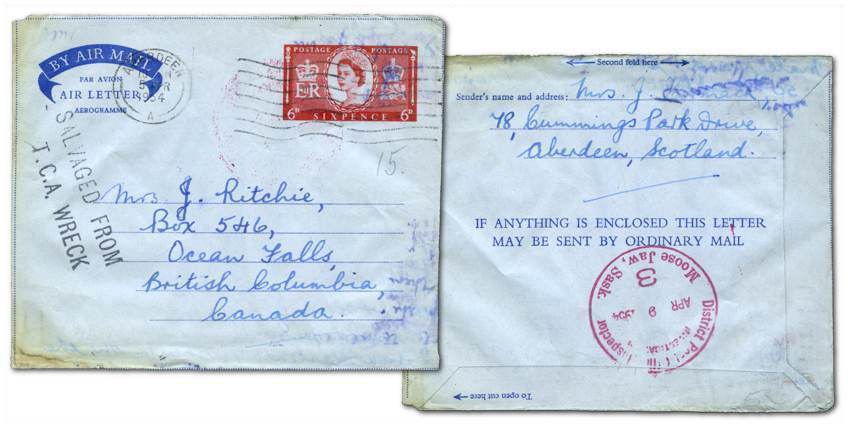

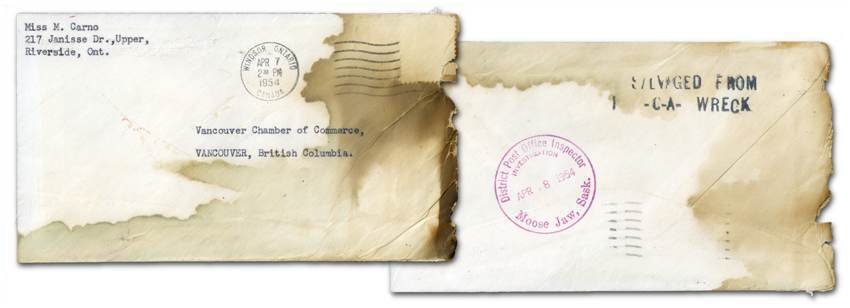

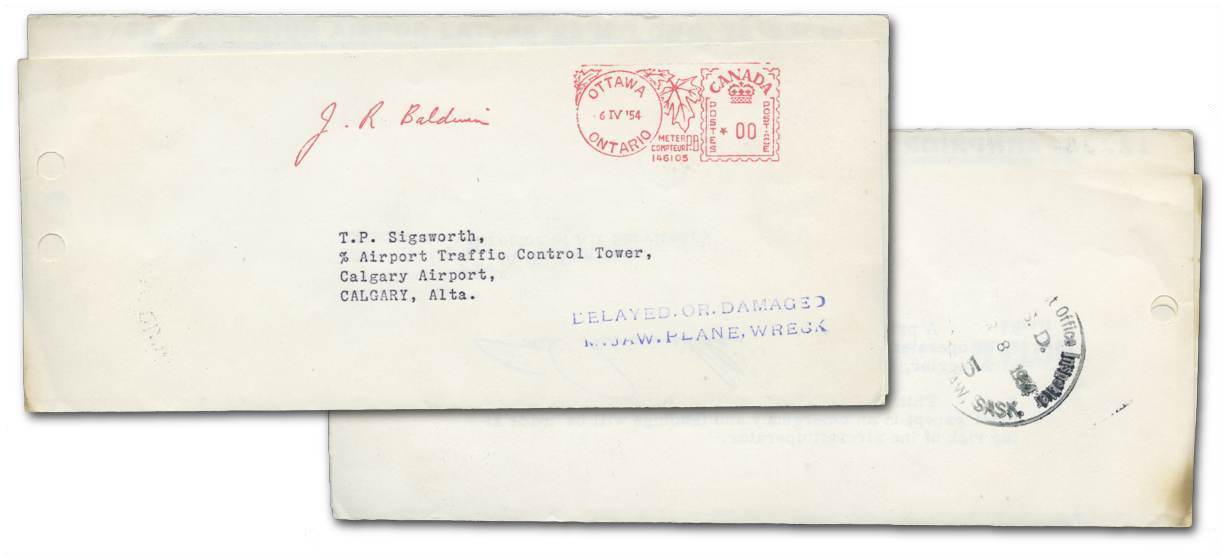

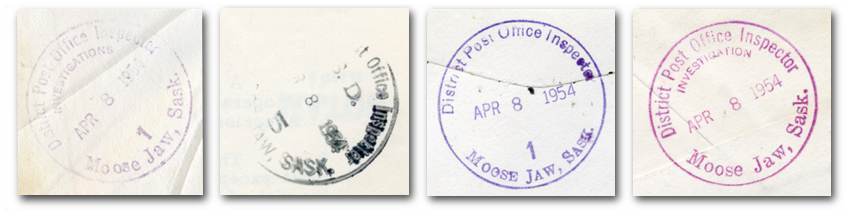

Much of the mail was burned or scorched, and much of it suffered water and smoke damage. By the end of the day of the collision, however, many salvaged letters had already been sent on their way in the mail stream. Most of the recovered mail appears to have been hand-stamped with various versions of the message that it had been salvaged from the T.C.A. wreckage, as well as a postmarks indicating the official nature of the recovery and the date the mail was processed in Moose Jaw.

One variety of the “Salvaged from T.C.A. Wreck” handstamp has hyphens between the airline initials rather than periods:

Another variety of the handstamp has periods separating each word — “DELAYED.OR.DAMAGED.MOOSE JAW.WRECK”:

Despite the inevitable chaos caused by the collision of the North Star and the Harvard trainer, by the end of the day postal officials had recovered and begun to forward many letters recovered from the wreckage of the T.C.A. North Star.

Ambulance covers to the rescue

The biggest challenge postal officials faced in the aftermath of the crash was identifying, if possible, and forwarding, if possible, some 700 kg (2,000 lbs.) of mail that was so badly damaged that it could not be forwarded without resorting to the use of “ambulance covers,” new envelopes into which damaged letters were inserted and posted to the recipients, if their addresses were intact, or returned to the senders if only the return addresses survived. As much as 30 per cent of the North Star’s cargo of mail was thought to have been lost.

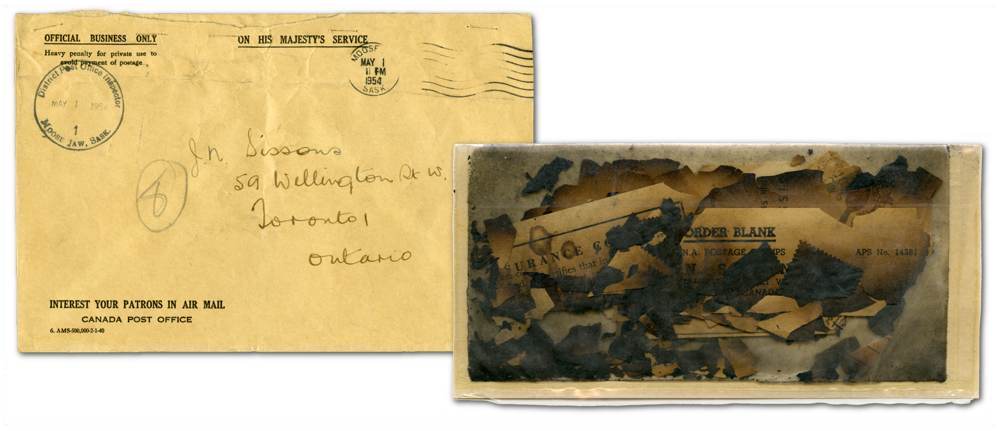

Among the covers that required an ambulance cover was one that apparently contained an order for stamps from the J.N. Sissons stamp company of Toronto. Since it couldn’t be delivered, it was being returned in an ambulance cover to Sissons, its contents little but the charred remains of an order form and postage stamps, just one of which is identifiable as a postage stamp.

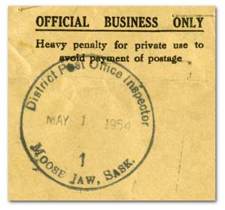

At the left is a detailed image of the post office examiner’s postmark on the ambulance cover shown above. Dated May 1, 1954 — 24 days after the collision between the TCA North Star and the Harvard trainer — it reveals the long and no-doubt-tedious process of recovering mail from T.C.A. Flight 9.

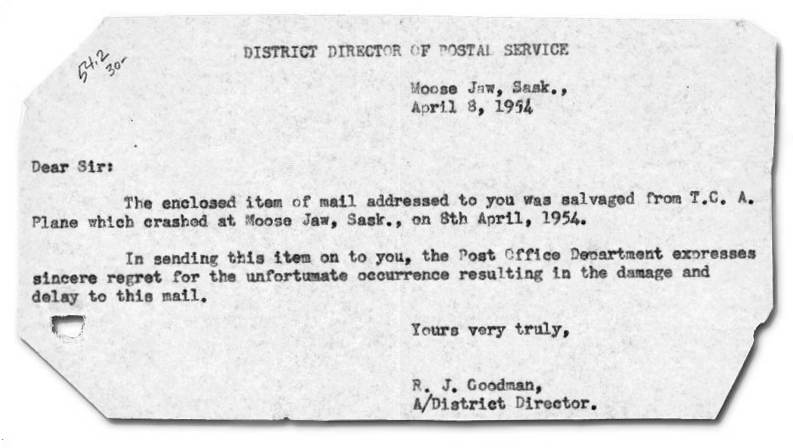

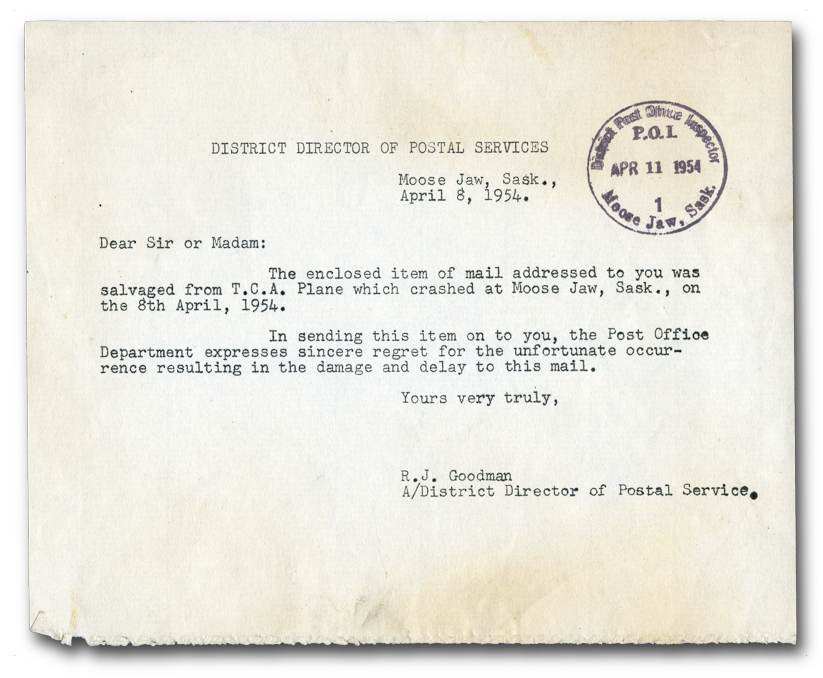

The Post Office Department was at pains to disclose the reasons for the delay of mail from the TCA North Star tragedy: Mail forwarded in ambulance envelopes normally included a standard written explanation about the delay:

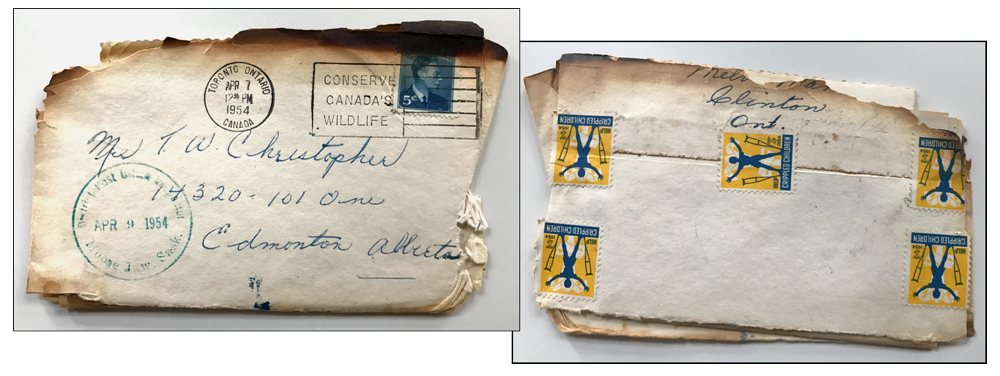

More artifacts from the Moose Jaw tragedy — very personal family artifacts — came to my attention when a Vancouver resident, Chuck Hamilton, contacted me by email in October, 2016. Only three months earlier, in August, his mother had given him a letter that he said had “… moved around with our family since the early 1950s.” The envelope was clearly a survivor of the crash of TCA Flight 9:

The return address on the flap of the cover was partially incinerated following the crash of TCA Flight 9. It appears to read “Melv… Man… / Clinton / Ont”. Chuck Hamilton noted in an email that “Melv… Man…” refers to Melva Manor, the name of the restaurant that served as his parents’ place of business as well as their home.

That return address raises a question: Why was the letter postmarked in Toronto when the return address indicates that the sender, Connie Hamilton, was living in Clinton, Ontario? The simple answer, in Chuck’s words: “I checked with my mother and she said that my father, Gord Hamilton, took the envelope to Toronto and mailed it since he would make the regular run to Toronto to buy supplies for the restaurant in those days. So they just sent it along with him.” That explains in part why the crash cover was postmarked April 7, 1954, even though the letter it encloses is dated April 4, a Sunday. There may, however, be other reasons for the delay in posting.

If Chuck’s mother didn’t have a stamp, she couldn’t have bought one since the post offices weren’t open on Sundays, or on Saturdays for that matter. Before 1985, when the the Supreme Court of Canada struck down the federal Lord’s Day Act, all commercial transactions were forbidden on Sundays.1 That might account for at least one day’s delay. She might also have started the letter on April 4, but didn’t complete it until shortly before giving it to Chuck Hamilton’s grandfather to mail as he left for Toronto, perhaps on April 7. Clinton is 209 km (130 miles) west of Toronto.

There is no doubt that Chuck’s father posted the letter shortly before 12:30 p.m. on April 7, which is the time that it was postmarked. In those days, rapid service was a point of pride for post office departments everywhere, and letters were usually postmarked within minutes of their arrival at a post office.

The “HELP CRIPPLED CHILDREN” Easter seals affixed to the back of the crash cover — one is shown at the right — are reminders that in 1954 the Salk polio vaccine was still being tested. In 1953, some 35,000 children became infected with polio. The sale of Easter Seal poster stamps, part of the March of Dimes campaign, funded polio research and supported the vaccination campaign that reduced the number of polio cases in 1957 to only 5,600. Today, polio has been eradicated in all but a few countries, including Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Nigeria, where polio vaccination programs are being resisted on religious grounds.

Chuck further explained the provenance of the letter:

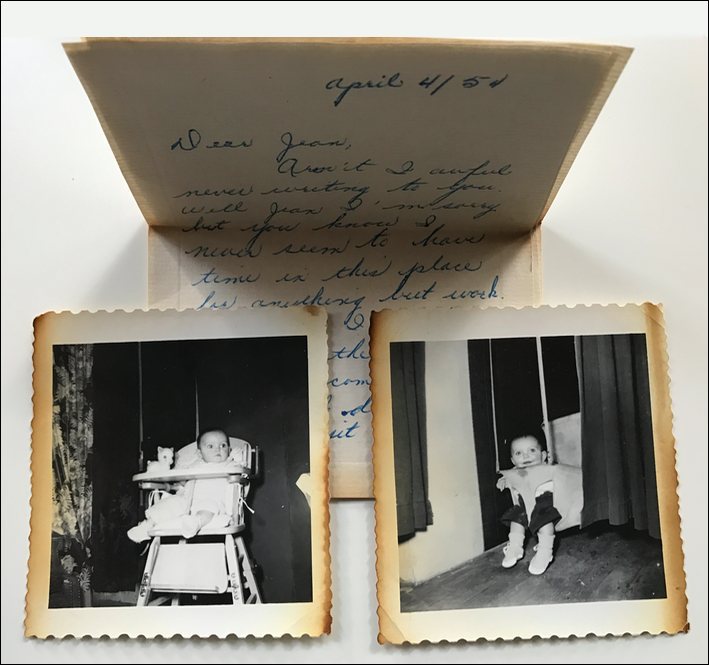

Our seriously scorched envelope was forwarded by Canada Post many months after the incident to my Aunt (Jean Christopher), then living in Edmonton. The envelope contains a letter (from my mother to her sister) describing the struggles of a young women and new mother in Clinton Ontario, as well as two slightly singed photos never seen by our branch of the family until this year.

Next, in Part 8: A book published in 2006, Mid-Air Moose Jaw, documents the crash; relatives of its victims come together in remembrance and shared grief, and Moose Jaw citzens erect a cairn in memory of the victims.

-

The Canadian Lord's Day Act of 1906 prohibited business transactions on Sundays. The act was declared unconstitutional in the 1985 case, The Queen versus Big M Drug Mart Ltd. Calgary police officers witnessed several transactions on a Sunday at the Big M Drug Mart, all of which occurred on a Sunday. Big M was charged with a violation of the Lord's Day Act. A provincial court ruled that the Lord's Day Act was unconstitutional, but the Crown appealed all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada. In a unanimous 6–0 decision, the Lord's Day Act was ruled an infringement of the freedom of conscience and religion as defined in section 2(a) of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. ↩︎