I survived a plane crash in the Black Range: (Part 1)

This web page was updated on February 26, 2020

When I was 19 years old and ignorant of the forces of nature as well as the physics of flight, it seemed like a good idea to try to get a ride in a U.S. Forest Service spotter plane — a “bird dog” — over a forest fire in the Gila National Forest in Southwestern New Mexico. It turned out to be a very bad idea.

I dig up a story

In the spring of 1962, I was working as a stringer — a part-time correspondent — for the Times of El Paso, Texas, covering news in my home town, Silver City, New Mexico and in the surrounding mining district. Times editor Bill Latham had given me free rein to write whatever feature articles I could dig up.

Fired with youthful enthusiasm and yearning for adventure, I decided that the annual summertime battles between the U.S. Forest Service and forest fires in the nearby Gila National Forest would make a great feature story. I interviewed Jack Foster, the forest’s fire control chief, who offered full support for my research. On Saturday, June 2, I drove to the Forest Service facility at the Silver City-Grant County Airport.

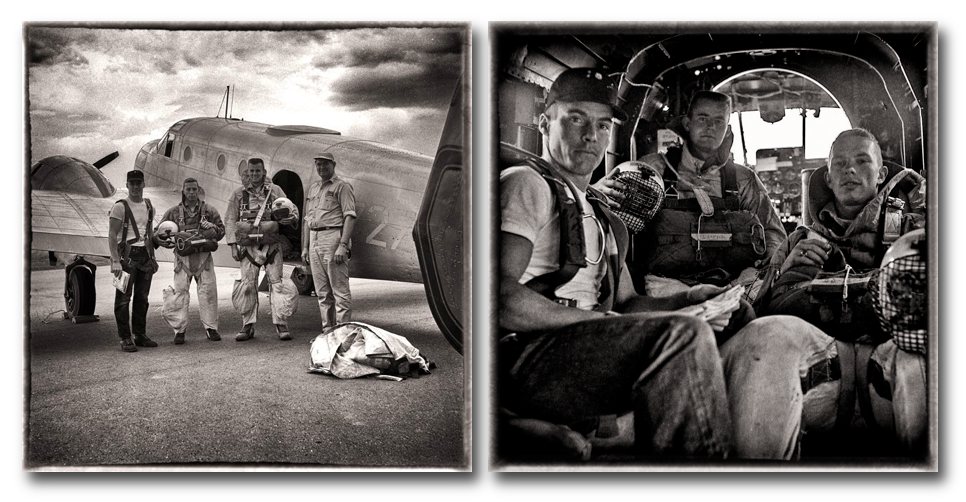

I interviewed smokejumpers, quiet college guys earning money for school, as well as a couple of professionals. Since 1940, smokejumpers had been dropping out of American skies like paratroopers to fight and subdue small fires before they became big fires. That summer they were leaping into space from a Beech 18, a twin-engined transport that first flew in 1937 and is still flying today. It’s sometimes referred to as a “Baby DC-3”.

I was content just to interview the smokejumpers, not join them. Call me chicken, but the idea of stepping out of an airplane over a trackless wilderness did not appeal to me. Besides, the exhilaration of smokejumping ends with the landing: from then on it’s just hard, hot, dirty work, and dangerous (although, statistically, smokejumpers are at no greater risk than other forest-fire fighters, not that either profession could be considered safe).

Aerial assault

Two helicopters were working on the Gila that summer. One was a French Alouette II, the first turbine-powered helicopter and holder of altitude and speed records for helicopters. The other was a little Hiller with a canopy like a big bubble — riding in it was like riding a motorcycle in the sky, and sometimes like riding a motorcycle just a few feet off the ground!

WWII-era “warbirds” — Grumman TBM Avenger torpedo bombers and a North American B-25 Mitchell bomber — were called on to make low-level drops of fire-retarding “slurry” in mountain air so thin and often so turbulent that no flight could be considered safe.

The slurry pilots depended on small bird-dog planes that flew at dangerously low level and slow speed so their pilots could check wind direction, visibility, the size of the fire, and hotspots most in need of cooling down. They directed the slurry pilots by radio, and then checked the effectiveness of the retardant after each drop.

It wasn’t possible to fly as a passenger in a TBM tanker, because there was only room for the pilot. TBMs were designed to be crewed by a pilot, turret gunner and radioman/bombardier/ventral gunner, but improvements in technology made the radioman/bombardier/ventral gunner little more than extra baggage; toward the end of the war, his duties were taken over by the pilot and turret gunner. When TBMs were converted to aerial tankers, their turret-gun turrets were removed and all but the canopy over the pilot was covered with metal panels; the belly of the plane, where the radioman/bombardier/ventral gunner was located, was turned into a tank for fire retardant, fertilizers, or pesticides, depending on whatever role the “new” TBM was assigned.

Nor could I fly in the B-25, because it was out of service that day. However, I could fly in a bird-dog plane, which was apparently considered to be less dangerous, and in the late afternoon, pilot Wendell Schroll invited me to join him on a flight into the Black Range to check out a small fire west of Hillsboro near McKnight Canyon.

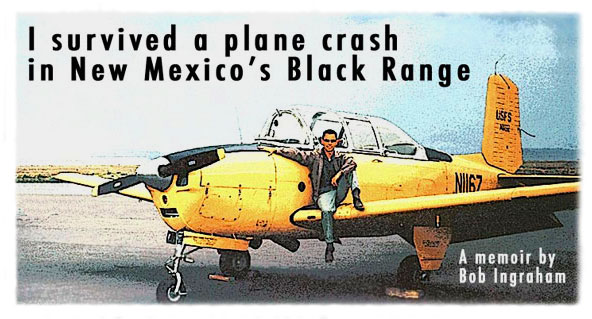

Wendell had flown in from Redding, California to help out with an especially active fire season. He was flying a single-engine Beechcraft T-34B Mentor, registration #N145Z, leased to the Forest Service by the U.S. Navy.

Derived from the famous V-tail Beech Model 35 Bonanza, the T-34 Mentor is a low-wing, tandem-seat trainer with a large bubble canopy. The Beech Aircraft Company built 423 T-34B variants for the Navy; they differed slightly from the U.S. Air Force’s T-34As, having differential braking for steering control on the ground instead of nosewheel steering, additional wing dihedral and, to cater to pilots of differing height, adjustable rudder pedals instead of the moveable seats of the T-34A.

Almost 2,000 T-34s in several variants were built, but the aircraft isn’t well known by the general public. My topical collection of airplanes on stamps includes only one postage stamp picturing the T-34, as well as one charity seal.

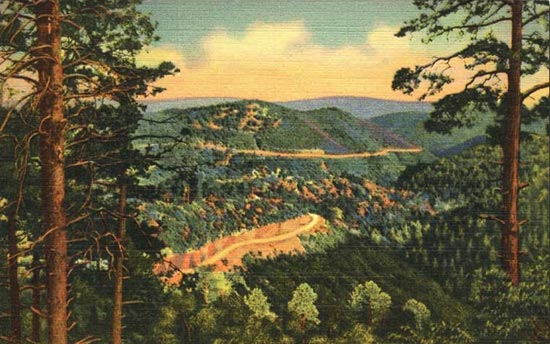

The Black Range, where Wendell and I were headed, is a heavily forested wilderness of deep canyons, rincóns (south-facing meadows on steep mountain slopes), streams, and grasslands on the eastern edge of the Gila National Forest.

The mountain range was aptly named, especially for that particular day: the towering cumulonimbus clouds that had boiled skyward over the Black Range in the late morning and early afternoon had solidified into a inky mass covering half the horizon. Lightning occasionally lanced earthward. Thunder grumbled softly but menacingly in the distance. Dust boiled off the white tailings dump at the Kennecott copper smelter in nearby Hurley, where my Grandfather Ingraham had worked as a machinist.

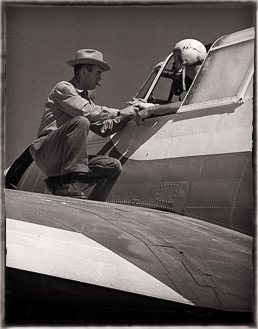

I loaded my Yashica-Mat camera with a fresh roll of 120 Tri-X high-speed film, followed Wendell out onto the tarmac, and climbed into the back seat of the T-34. Wendell gave a quick tutorial about the intercom and harness and quickly went through his pre-flight checklist. Soon we were climbing away from the airport into one of the ugliest skies I had ever seen.

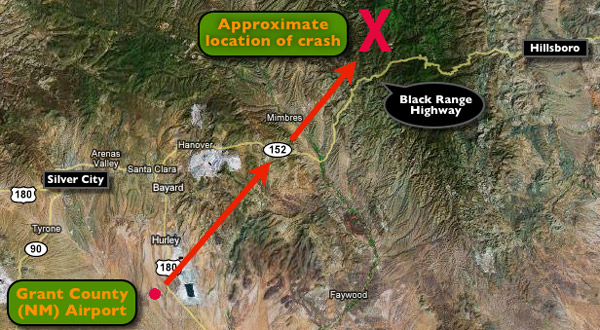

Our flight path, on a northeast heading, took us over Hurley. A short hop over Geronimo Mountain gave us a spectacular view of the huge open-pit copper mine at Santa Rita. From our perspective, the famous Kneeling Nun rock formation at Santa Rita just looked like a big rock, and not the semi-religious icon it had become. Within a few minutes we had crossed the narrow Mimbres Valley and were climbing into the high, stormy wilderness of the Black Range.

About 20 minutes after takeoff, we located the fire — a dead pine tree, called a “snag,” had been hit by lightning — and rendezvoused with a TBM. We were near Hillsboro Peak, about 80 km (50 miles) northwest of the airport and some five miles north of the Black Range Highway. Below us was a nearly vertical landscape, of deep, rocky canyons and thick forest, decidedly unfriendly to low-flying aircraft. Some wind made the flight slightly “bumpy”. We were almost skimming the tops of the trees near the top of a long ridge, unaware that we were seconds away from a sudden, uncontrolled, inverted spin into the forest.

Next, in Part 2: My official statement, written for U.S. Forest Service crash investigators.