I survived a plane crash in the Black Range: (Part 2)

Following my survival of the crash of a U.S. Forest Service T-34B Mentor "bird-dog" plane in the Gila National Forest, the Gila's "fire boss," Jack Foster, asked me to write a statement about my experiences. Jack's request came too soon after the crash, although, in truth, there might never have been a good time to ask. No one knew it, but my brain, and my memories, had been well scrambled, at least in detail:**

My statement includes errors about the date of the crash that certainly indicate possible mental confusion. I believe that I was still suffering from the concussion I had, although at the time, no one, including my doctor, mentioned the possibility of a concussion, even though I had been knocked unconscious moments after the Mentor plunged into the forest and remained “out” for several minutes. Today, any period of unconscious following a blow to the head qualifies the concussion as “severe”.

I suspect that my thinking was fuzzy. Regardless of long I was unconscious, unconsciousness for any period as a result of physical trauma can be taken as unambiguous evidence of severe concussion. And concussion, of course, can result in confusion, memory loss, nausea, and headache, all of which I experienced to greater or lesser degree following the T-34 crash.

In my last paragraph, I write that my evacuation by helicopter from the crash site was my first helicopter ride. Obviously, my brain was scrambled eggs! My first helicopter ride, two or three weeks before, was in the same Hiller UH-12A Raven that evacuated me from the crash site. Previously, I'd flown in the Raven on three other occasions, and once in the French Alouette II jet-turbine helicopter that the Forest Service had leased that summer. My evacuation flight in the Raven was my fifth helicopter ride.

Was I simply being careless about dates and facts in my statement? I don't think so. I was knocked unconscious in the T-34's descent through the forest, and have no sense of how long I was "out". It could have been a minute. It could have been an hour. Regardless of how long I was unconscious, unconsciousness for any period as a result of physical trauma is unambiguous evidence of severe concussion. And concussion, of course, can result in confusion, memory loss, nausea, and headache, all of which I experienced to greater or lesser degree following the T-34 crash.

My original statement as provided to the Forest Service did not include the subheadings that occur in the following transcription. Nor did it include the photographs that appear with it on this web page.

My Statementt

As a correspondent of the El Paso Times of El Paso, Texas, I was working on a feature story concerned with forest fire-fighting tactics in the Gila National Forest. On

May,June 2, there appeared to be considerable air activity of Forest Service planes, so I decided to drive to the Grant country Airport where the Gila Forest air support facilities are located. I arrived there about 1:00 p.m. and soon after contacted Fire Control Staff Officer Jack Foster. He gave me permission to talk with any persons concerned with the operation and to take any pictures I wished. In regard to my request for a flight on the Forest Service aircraft, Mr. Foster said it was not possible at the time but suggested I keep in touch with him. I spent the early part of the afternoon gathering information and taking pictures.About 3:15 P.M., I was talking with Foster and Jumper foreman Dick Tracy. A yellow F.S. T-34 pulled up on the apron near us and Mr. Foster said he might be able to arrange a flight in this aircraft later in the day if fire conditions would permit. After our conversation, I went to meet the pilot, Wendell Schroll, of Redding, California.

About 4:00 P.M., Schroll told me we were to take off immediately on an observation mission for a TBM borate plane that was to douse a small fire in the Black Range. I estimate our take-off time as about 4:05 P.M.

I saw nothing but trees

On our

thirdsecond pass we flew in "formation" with the TBM so I could get a picture of the drop. Through an error of mine, I was unable to get a picture of the drop. Then we started to turn for another pass over the fire to check the effectiveness of the borate. I was occupied with something to do with my camera when I sensed that the plane had gone into a steep bank. We were, in fact, upside down. I looked "up" and saw nothing but trees — and then we hit the trees.I believe I was conscious for most of the time during our sudden arrival, for I remember what seemed to be a long period of violent bucking and interminable noise. I also remember thinking that I was not going to die in that way.1 The next thing I remember was not knowing whether I was dead or alive.2 Then my eyes popped open and I saw my own blood dripping from some place onto the dust. There was no sound, no dust in the air. I was hanging upside down in my seat, and when I realized this I started kicking and pawing at the restraining harness. Then I remembered the buckle assembly and released it. Out I tumbled and up the hill I scrambled, not really knowing what I was doing. I had only one shoe on, and that was half torn off. When I reached the ridge top, I stopped to try to think. Although I was a bloody mess, I thought I had only four wounds — one on my head, two minor ones on my left hand, and a bad one on my left knee.

I soon decided I was not having a bad dream. Nevertheless, I knew, or thought I knew, that the pilot was dead. But swiftly the thought that if I were alive, he could be too, came to me. Back down the ridge I went and halfway down I heard him moan. I found him against the engine, out of his seat and helmet, with his left arm quite out of position. He opened his eyes and asked me who I was. I told him as much as I knew, but he couldn't remember. I did as much as I could to make him comfortable, but I was unable to move him from the engine, which was burning him. He weighs 220 pounds.3

A potential inferno

Shortly we heard a plane and back up the ridge I went. It was clearer up there, and I also had a red shirt which I thought the pilot might see. I saw the plane, but it must have been a good two miles distant. It soon disappeared, and I went back down to Wendell. He was complaining of the cold when I got back. At his instruction, I found his flying suit and jacket in the wreck. (Sometime in this period, more planes started flying much nearer to us.) I covered him and started searching for matches to build a fire. I knew full well the ground and trees were soaked with about 300 gallons of fuel and oil, but I didn't connect my hoped-for small fire with that potential inferno. As you can see, I still wasn't thinking too clearly.4

Planes were still flying all around; they would fly close, then zoom far away. Actually, the Silver City based T-34 had spotted us on his first pass over the wreck, but no one bothered to signal us in some manner. We did not know we'd been spotted until Smokejumper Dick Tracy yelled at us. He and another jumper had jumped from a Twin Beechcraft.

Tracy arrived on the scene first. I told him I was not seriously hurt, but that Wendell was. He made Wendell more comfortable and gave us both a shot of Demerol. Then, more supplies, including first-aid equipment, water and paper sleeping bags, were dropped from a Twin Beech. I drank quite a bit of water. Kirk Samsel, the other jumper, arrived at this time. I soon became sick, probably from the Demerol. I believe Dick and Kirk were patching Wendell at this time. I was getting quite sleepy when Dick gave me his radio. He said he wanted me to tell him if anyone called. He didn't tell me that we couldn't receive any transmission in our canyon. Anyhow, I was happy knowing I was helping in some small way.

Through the night I woke about every half hour. Early in the evening one of the boys told me the rescue party, including Dr. Claran C. Cobb, was on its way in overland. I occupied my time when I was awake by listening to the night birds and watching for shooting stars.

Rescue

At about 2:30 A.M.,

May 3, we first saw the lights of the rescuers. A little later we could hear them talking, but it was a good hour and a half5 before they reached us.They finally did arrive with more blankets. I was glad for that, because it is cold at night any time of year at 8,000 feet elevation. Dr. Cobb was among the first to arrive. He worked with Wendell for about an hour, and then did a little work on me. Jack Foster arrived shortly after Dr. Cobb, and I don't believe that ever before was anyone so glad to see me. He asked if I thought the crash was due to engine failure. I told him I was sure it was not that.

I did little, if any, sleeping from then on. The men started clearing the helipad in earnest, and it soon started growing light. Awhile before sun-up, I was carried piggy-back fashion to the helispot by Dick Tracy. There we waited for the helicopter to come. The Alouette was the first to come. Wendell was loaded into it. I was protected from the rotor blast by a smokejumper. After a short wait, the Hiller came to get me. I got in with assistance and sat in a normal position. My

first6 fifth helicopter ride took only about 10 minutes. We landed in front of Hillcrest General Hospital and I was carried into emergency by several men.Robert Ingraham Jr.

One of my lifelong regrets is that I didn't get the photo of the TBM tanker dropping its load of fire retarding "slurry" onto the fire. For decades, I have reproached myself for the "error" that led to missing that shot, but the thought came to me recently that I may actually have taken a great photograph. Here's why I thought that I may have flubbed the opportunity, and why, even if I did get a great photo, no one would ever see it.

The Yashica-Mat twin-lens reflex camera allows framing of photographs by looking down at the ground-glass screen, which is shaded by a pop-up hood, or through its "sports finder," consisting of a square hole punched in the back of the pop-up hood and a knock-out in the front. When the sports finder isn't in use, the opening at the front is covered by a metal flap, hinged at the bottom. The photographer activates the sports finder by swinging the metal flap down and locking it against the ground glass, then peering through the small square to compose the image.

!!! IMG FILE '/Users/Bob/Sites/ephemeral/html/imgs/crash-using-yashica-met-sports-finder.jpg' NOT FOUND !!!As photographic technology, the Yashica-Mat's sports finder is more 19th than 20th Century. In addition, it has a design fault: if you bump the focussing hood even slightly, the metal flap pops up, blocking your view. I was looking through the sports finder to compose my photograph as the TBM made its drop of fire retardant; using the ground-glass screen was impossible in the confines of the T-34's cockpit.

The moment I snapped my picture, the T-34 hit an air pocket and the sports finder bumped against the inside of the plane's canopy, which instantly caused the flap to swing up and block my view. I assumed at the time that I had failed to take any photo at that moment, much less a great photo, but I realized only recently I was wrong in that assumption, for this reason: after my apparent failure to get a good photograph, I looked down at my camera to advance the film and cock the shutter in case I got another opportunity for a photo, any photo. But here's the thing: If I hadn't taken a photograph, I couldn't have advanced the film or cocked the shutter. Ergo, I had taken a photograph, but that thought didn't occur to me because that was when I realized that something about the flight didn't seem right, and of course it wasn't: when I looked up, the trees on the ridge seemed to be growing down toward us from the sky, and in the next instant the T-34 struck the trees.

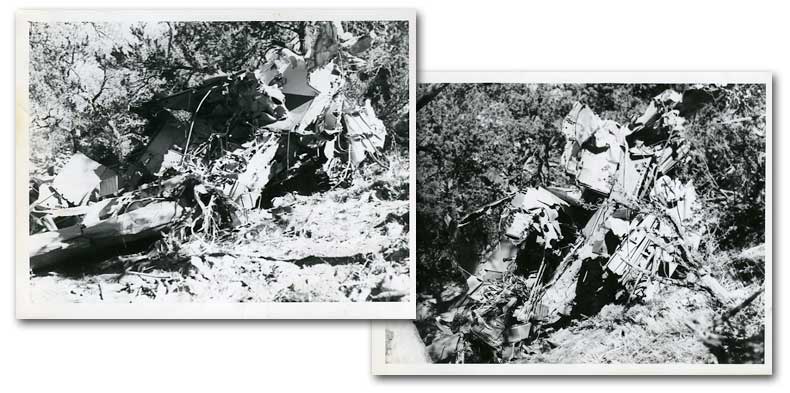

Whether I'd actually taken the photograph I wanted is a moot point. My camera, in addition to Wendell Schroll, myself, and the T-34, was also a victim of the crash. As I limped about the crash site, waiting hopefully for rescue, I found my camera at the base of the large ponderosa pine, no less damaged than the T-34: when I picked it up, the back fell off and the exposed film fell out. The focussing hood was gone, the sides were caved in, the ground glass focussing screen was shattered, and the film-winding, shutter-cocking crank was bent into a "U".

I had been surprised when that flap popped up to block my view: I'd only had the Yashica-Mat camera a few weeks, and hadn't yet learned its idiosyncrasies. (Note to self: When taking a particular photograph is very important, make sure I'm very familiar with the camera I'll be using!)

Next, in Part 3: More details about the crash and our rescue, and speculation about the cause or causes of the crash.

-

Did I or did I not believe that I was going to die? I recall “knowing* that I was going to die. No one, I thought, could possibly survive a plane crash that seemed to be turning a powerful metal aircraft into a pile of junk. Yet I say in my statement to the Forest Service that I didn’t believe I was going to die. I don’t know why I wrote that; all my life I have believed, before I was knocked unconscious,I was sure I was living my last day on earth. ↩︎

-

My statement that I didn’t know if I was still alive, or dead, after the crash, conflates two thoughts. When I first regained consciousness, I remembered exactly what had happened to the Mentor, if not why, and I certainly knew that I had survived. However, after running in a panic up the ridge we had crashed on, I sat down on a log to collect my thoughts. One thought overroad all others: I really didn’t know if I was alive or dead. I’d heard that people pinch themselves to determine if they are alive. I pinched myself. Ouch! I seemed to be alive. And the forest around looked and smelled very much like the Gila Forest I had come to know, not the Heaven I had been taught to believe in, with its streets of gold and a chorus of angels. I decided that I was alive. I was sure, however, that Wendell was surely dead. Of course, that illogical, because I was still alive. Reluctantly, I climbed back down the ridge to find Wendell in bad shape, semi-conscious, and lying on the engine, which was burning one of his legs. He was unable to move by himself. The left temple of his regulation, fibreglass U.S. Air Force helmet was crushed. ↩︎

-

In one of his newspaper accounts of the crash by my father notes I was able to drag Wendell off the Mentor’s engine, but I wrote in my report to the Forest Service that I was unable to do that. I’m pretty sure that I could not have moved Wendell: Not only was he a much bigger man than I was, but because of my own injuries I was rapidly losing strength and soon was unable to stand on my own. I won’t blame my dad for his apparent error. For all I know, I told him, in my muddle, that I had moved Wendell off the engine. ↩︎

-

I didn’t find the matches that Wendell sent me to find in the aircraft’s storage compartment. If I had, fire would almost certainly incinerated the crash site, not to mention Wendell and me. ↩︎

-

I will never be certain how long the ground party took to arrive at the T-34 crash site, but I am sure that we saw their lights and heard them talking across McKnight Canyon in the very early morning hours, perhaps around 1:00 a.m or 2:00 a.m. And I know that they didn't reach us until dawn, which at that time of year and latitude is around 5:00 a.m. In other words, it took them some at least three hours to clamber down to the bottom of the canyon and then climb up to the crash site on the opposite side of the canyon. ↩︎

-

My evacuation flight was not my first ride in a helicopter. While I was gathering information for my story, I had enjoyed flights in two different helicopters — the Raven and the Alouette II — for a total of four other flights before my evacuation. The first of those flight was my first flight in a helicopter. I have no idea why I wrote that the evacuation flight was my first helicopter ride. I can say this: during the flight to the hospital I was terrified that the helicopter would crash. It would be the only time in my life that flying frightened me, and I would have many more flights, some of them in extremely dangerous circumstances. ↩︎