I survived a plane crash in the Black Range (Part 4)

My born-again Yashica-Mat

On the day of the T-34 crash, I was shooting with a Yashica-Mat twin-lens, medium-format camera, a Japanese version of the German Rolleiflex. It was the first of several high-quality cameras I would own, and the only one that would be "re-born," years after it collided, fatally, with a ponderosa pine tree.

I had bought the Yashica-Mat, and insured it, only a few weeks before. After the crash, and after I had decided that we were still — amazingly — alive and couldn’t do much except wait for someone to rescue us, if they were going to rescue us, I went looking for my camera. I found it. Or what remained of it.

It had been in a case with a strap around my neck; I found it at the base of a large ponderosa pine. The strap was broken. The focussing hood, screen, and reflex mirror were gone. The back was gone, the sides of the camera were caved in, and the crank which wound the shutter and advanced the film was bent into a “U.” When I picked the camera up, the ruined film fell out of it. But the lenses were undamaged, and lenses are the heart of a camera. Insurance paid for a new camera — a Nikon SP rangefinder camera.

A year and a half later I was a sailor in the U.S. Navy, with orders to report for duty at the U.S. Naval Hospital in Yokosuka, Japan. I took the remains of the Yashica-Mat with me, and at my first opportunity took it to a camera store. They sent it to the Yashica factory in Tokyo. Two weeks later, I got it back, almost like new, but with some scratches. The film-advance/shutter-cocking crank was no longer bent in a “U,” but did have have a slight bend and torque in it. Total cost? U.S. $20.

I used the Yashica-Mat for several more years and eventually traded it in on another camera. Another 20 years passed, and the camera came back into my possession, but that’s another story….

God was NOT in our cockpit!

I don’t view my survival or Wendell’s as miraculous in any sense. Crash survivors often credit “the will of God” for their survival, but that’s nonsense. Wendell and I survived simply because we weren’t killed, despite the odds. If I credit God with saving our lives, then, to be consistent, I must blame God for taking the lives of so many other people in similar mishaps! I have more faith in physics and chance than in any such capricious “God.”

The science of physics provides a far more likely explanation for my survival and that of Wendell Schroll than any myth-based reason. Any moving object with any measurable mass develops “energy of motion,” called kinetic energy by physicists. As long as the object maintains its speed, it maintains its energy. As it slows, it bleeds energy into its surroundings until it stops, at which point it has no kinetic energy at all. Any gun firing any bullet provides a useful analogy.

Anyone shot at point-blank range is in trouble because the bullet has last almost none of its kinetic energy. When it hits the victim, most of its kinetic energy is transferred in an instant to the victim. If the victim’s body stops the bullet, his body absorbs all of the bullet’s kinetic energy, and may sustain fatal wounds.

Anyone who is shot from a long distance will be in much less danger because the bullet, pushing through the air between the gun and the victim, gradually loses its kinetic energy. The greater the distance, the greater the loss of kinetic energy. If enough of its energy is lost, it can simply bounce off the victim. This explanation is based on personal experience.

On March 4, 1966, I was sitting with a friend on a hill in Quang Ngai Province, South Vietnam. Far in the distance we could hear gunfire from a firefight between other U.S. Marines and communists. Suddenly I felt a sharp pain on the inside of my right thigh. I looked down and saw a large rifle bullet on the ground. I picked it up. It was warm and had tiny scratches on it. It had travelled a long way after it was fired, and had lost virtually all of its kinetic energy before it hit me. I took that incident as a good omen. However…

The next morning, when my company got orders to ascend a low hill, we were ambushed by a communist unit composed of Main Force Viet Cong and elements of a North Vietnamese regiment. I was shot through my right thigh at close range by a communist rifleman just as I was starting to care for a wounded Marine. Because the bullet had been fired at close range, it had lost little kinetic energy. It punched through my outer fatigue pants and through my thigh as if they weren’t there. It apparently struck my right femur just forward of the bone’s midline; the femur shattered and the bullet tore itself into fragments which burst through my inner thigh in a cloud of blood, bone shards, and bits pulverized flesh, leaving behind a legacy of pain, disability, and emotional trauma.

Identical physics explain the T-34 crash, a crash which could have killed me and Wendell Schroll, but didn’t. If the plane had dived nose first into the ground, or if it had been flown straight into a cliff, I wouldn’t be writing this. The plane’s considerable kinetic energy, which included the kinetic energy stored in my body and in Wendell’s because of our speed, would have been passed almost instantly into the ground, leaving our bodies behind as bits of useless flesh, blood, and bone.

In print at last

My full-page feature story was published in the El Paso Times on Sunday, July 22, 1962, and was even mentioned in an editorial in the same edition. (Readers may note an error in my feature story: I wrote that smokejumpers aim for trees to break their fall. They don’t do that, for obvious reasons that weren’t obvious to me at the time! I got more than a bit of good-natured ribbing from the smokejumpers for that gaff.)

An intact T-34

I had one more encounter with a T-34. It was the sister ship to #N116Z, doing the same bird dogging that #N145Z had been doing. I didn’t fly in it, but I decided I needed a photograph of it for posterity. Later that summer, when I was well-healed from my injuries, Carol Schmidt, my girlfriend, and I drove out to the airport, and she took this photo:

In 2018 I decided to return to one of my teenage hobbies, building scale-model aircraft, but with this difference: I would attempt to make them look like real airplanes rather than the toy-like models I slapped together and slopped paint on in my teens. My first kit purchase was a 1/48-scale T-34B Beech Mentor by the Minicraft model manufacturer. I spent several months on it, making at least three mistakes every time I sat down to work on it, and even losing a critical piece, but it looked pretty decent at the end:

In the news again

Almost a year after the crash, on May 22, 1963, the T-34 crash was in the news again when smokejumpers Dick Tracy and Kirk Samsel received a joint “Superior Service Award” for “heroic actions in parachuting under extremely hazardous conditions”. The story, appearing in the El Paso Times, notes that they had earlier received $300 performance awards from the Southwest Region of the U.S. Forest Service, and that Vice President Lyndon Johnson spoke at the ceremony in Washington. It also incorrectly names the passenger as “Robert M. Ingraham, Jr.” That’s my father!

By the time Dick and Tracy received their awards, I was in the U.S. Navy, training to be a hospital corpsman. While the physical injuries I sustained in the crash of the T-34 Mentor were relatively minor, I had suffered two near-death experiences, the first while the plane was tearing through the forest, violently tearing itself to pieces as it collided with trees and threatened to dismember Wendell and me, the second when I awoke and realized that no one knew we had crashed deep in a wilderness and that nightfall and falling temperatures were just a couple of hours away. Without water, food, or shelter we could have died from exposure before rescuers found us.

Victims of life-threatening trauma commonly develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is what happened to me as a result of the crash, although I wasn’t aware of it. I began to think of the crash as little more than an interesting experience, but I had twice faced the possibility of death, and depression and anxiety descended on me like a shroud, although I attributed how I was feeling to my continuing financial dependence on my parents, my dislike of college, and my strong urge to leave my small-town roots behind and start learning about the rest of the world.

When I complained to a friend about my unhappiness, she suggested that I join the Navy. On October 16, 1962, four and half months after the crash, I took my oath of allegiance and embarked on another adventure. I was trained as a hospital corpsman, spent two years working at the U.S. Navy hospital in Yokosuka, Japan, and then, much to my surprise and not at all in line with my plans for the future, I was ordered to attend Field Medical Service School at Camp Pendleton in California. In August, 1965, I was ordered to join the 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines of the U.S. Marine Corps’ 1st Division. My battalion soon embarked for several months of additional training in Okinawa. On January 28, 1966, 3rd Battalion made its first amphibious landing since the Korean War, landing on a beach south of Chu Lai in Quang Ngai Province, South Vietnam. On March 5, 1966, less than four years after my T-34 crash, my Marine Corps company, Lima Co., was ambushed by a combined force of Viet Cong and soldiers of the 21st Regiment of the People’s Army of Viet Nam. I was severely wounded when a communist soldier shot me through my right thigh, but I was lucky — again: 10 Marines in my company were killed that day. You can read about my adventures in Vietnam on my web pages, titled 37 Days in Vietnam.

The U.S. Forest Service: “anti-historical”

The crash of F.S. T-34 Mentor #N145Z, although it was headline news at the time and helped define my sense of mortality, was trivial in a greater historical context.

Today, except for my own artifacts, a few posts that I have made to various internet groups, and the handful of newspaper stories which are, presumably, hidden away in newspaper morgues or briefly recorded on various media, there is virtually no record of the crash in existence.

U.S. Forest Service records go back only to 1974; in Young Men and Fire — The True Story of the Mann Gulch Fire, author Norman Maclean writes of his frustrations in trying to obtain information about the tragic deaths of 12 smokejumpers that occurred in 1949 in Montana. He characterizes the Forest Service as a “…fairly unhistorical outfit, sometimes even anti-historical.” I have been stymied in my own attempts to work with the Forest Service to learn the precise location of my own crash; a forest service employee told me in an email that Gila National Forest records from 1962 had been destroyed.

And now they are gone…

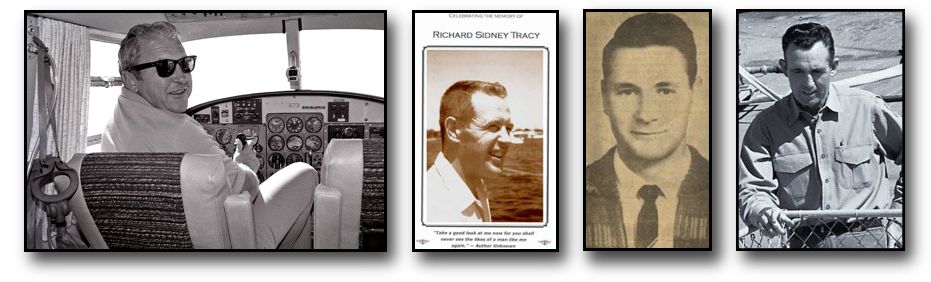

As I write this memoir, I am keenly aware that I have survived four of the men who figured most prominently in the small drama of the crash of “my” T-34: Wendell Schroll, Dick Tracy, Kirk Samsell, and Jack Foster.

That they have pre-deceased me is not surprising; they were all older than I by a decade or more. Here are brief obituaries for each of them:

Wendell Schroll, Pilot — According to Ancestry.com, a Wendell Schroll died at age 74 on May 28, 2003 in Upland, California, near LA/Uplands Airport, location of the air operations centre of the Forest Service’s Pacific Southwest Region. Wendell did not, apparently, have a life-long flying career: About a year after the T-34 crash, when he had recovered from his multiple injuries and was flying again, he was working with a lathe in his home workshop when a chisel broke and blinded one eye, making it impossible for him to fly again.1

Dick Tracy, Smokejumper — Dick Tracy died at age 73 on March 27, 2006, in Redding, California. Dick was born April 7, 1932, in Pollock, S.D. He served in the U.S. Army during the Korean War. In 1968, he moved from Silver City, NM to Shasta County, California where he became supervisor for the Redding Smokejumper Unit. Dick was a life member of the National Smokejumper Association.

Gaylord Kirk Samsel, Smokejumper — Kirk Samsel was killed September 9, 1994, at age 61, when his classic Piper Cub (model J3C-65) crashed in Montana. Kirk had homesteaded in Alaska earlier in his life; the Anchorage Daily News ran the following story:

On the late morning/early afternoon of September 9, 1994, a Piper J3C-65, N42056, registered to and being flown by Gaylord K. Samsel, a certificated private pilot, was destroyed during a collision with upsloping terrain following a loss of control in flight approximately five nautical miles northwest of Dixon, Montana. There was no fire and the pilot and passenger were fatally injured. Visual meteorological conditions with strong northwesterly winds and gusts prevailed midday on September 9th, and no flight plan had been filed….

Kirk was born Aug. 14, 1933 in Missoula, Montana, home of the famous Missoula Smokejumper School.

Jack Foster, Gila Forest Fire Control Officer — Jack Foster died at age 89 on July 23, 2004 in Tucson. From his obituary as published in the Tucson Citizen:

…He will be remembered for many things, including his 33-year government service as Maintenance and Construction Supervisor of the Prescott National Forest and culminating as the Fire Control Officer of the Gila National Forest, based in Silver City, New Mexico. He was instrumental in the development of slurry facilities and operations for firefighting in the Southwest….

-

Although it has not been confirmed that this Ancestry.com record concerns the pilot of FS #N145Z, it seems unlikely that the Ancestry.com record concerns another Wendell Schroll. ↩︎