Idlewild in sight — At flight’s end, safety eludes an Italian airliner (Part 3)

Benjamin Franklin had a lot to say about time. Among his aphorisms: Time is money & You may delay, but time will not. xxx Following the Second World War, and taking Franklin’s aphorisms to heart, airlines recognized that the most valuable commodity they could offer the travelling public was time well used, but it was a goal that could only be reached if they could demonstrate that their airliners were not just fast, but were also comfortable, quiet, and, to the extent possible, luxurious.

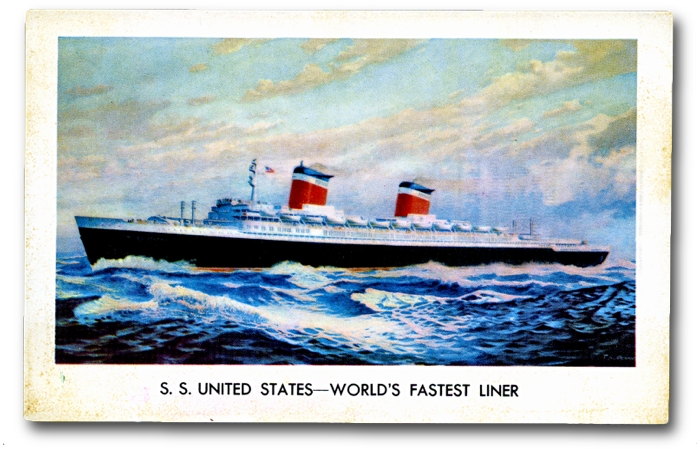

In prior decades and for a few years after the war, the great shipping companies of Europe had competed for the Blue Riband, an unofficial accolade conferred on passenger liners in regular service crossing the Atlantic Ocean in regular service with the greatest speed. To this day, the names of Blue Riband winners like Queen Mary, Lusitania, United States, and of course Titanic flesh out the lore of transatlantic ocean liners.

It was Titanic, of course, which came to grief in 1912 when it struck an iceberg and sank 400 miles (644 kilometres) south of Newfoundland. It wasn’t the iceberg’s fault. The fault lay in the corporate concept of “press-on-itis”.1 To make a profit, transatlantic shipping companies had to cater to every desire of their wealthiest passengers, embark as many paying passengers as possible, and sail between Europe and North America in the shortest time possible.xxx

Titanic’s captain, Edward Smith, was aware of warnings about possible encounters with icebergs as the ship sailed from Queenstown, Eire, on April 11, 1912, but in the interests of arriving in New York City in a timely manner, and possibly to establish a new record for a transatlantic crossing, he failed to order a reduction in the ship’s speed when the ship approached Newfoundland and its infamous icebergs. At night on April 15, a lookout spotted the fatal iceberg, but the sighting was too late: despite an order from the bridge to alter course, the ship’s massive kinetic energy guaranteed that it could not answer its helm in enough time to avoid a collision.

Capt. Smith, of course, paid dearly for ignoring safety in favour of speed: one rumour circulated after Titanic plunged to the bottom that he had shot himself. Another had him swimming with an infant in tow and putting the child on a lifeboat before slipping beneath the water. It is commonly held, however, that Smith followed the marine tradition of ships’ captains remaining going down with their doomed ships. It’s worth noting that that tradition applied in full to the captains of airliners, who, like their passengers, had no lifeboats at their disposal.

Much of the profit by transatlantic liners, in fact, came from transporting European immigrants to the United States and Canada as cheaply as possibly. As a result, many shipping lines treated immigrants little better than cattle, keeping them below decks for much of the voyage and supplying them with the necessities of life but not the pleasures. As the 20th Century drew close, shipping lines began to provide immigrants with small cabins, better food, and a bit more “freedom of the ship,” but they still reserved their best treatment for the rich and the famous, who enjoyed large cabins, deck chairs, squash courts, casinos, bars, swimming pools, concerts, dance halls, fine cuisine prepared by European chefs and served on the best china, and even dance orchestras.

While wealthy passengers no doubt appreciated the luxuries of an Atlantic crossing, every crossing was a race: The sooner those passengers reached their destinations in North America or in Europe, the more time they had to transact business. And the fastest crossings were fast indeed: the all-time record holder for the Blue Riband was S.S. United States, whose maiden voyage began July 3, 1952. For the next 17 years, United States maintained an average crossing speed on the North Atlantic of 30 knots (56 kph, or 35 mph). It normally completed the crossing in about four days (but still four times longer than the first flights of Pan Am flying boat between Southhampton and New York City).

While an iceberg sank Titanic, it was the airline industry that sank the great shipping companies.

In the century following the Great Gold Robbery, while trains more than doubled their speed and ocean liners offered ever greater speed and luxury, airliners left both ocean liners and trains in the figurative dust. The “protagonist” of this narrative, LAI’s Douglas DC-6B, was a variant of the company’s DC-6, which itself was an enlarged, faster version of the DC-4, which had done yeoman’s duty carrying troops and war matériel to combat theatres around the world. In fact, there were two versions of the DC-6B, a version for domestic flights and a trans-ocean version with greater fuel capacity, greater takeoff weight, and engines which provided an additional 100 horsepower each.

The DC-6B cruised at 315 mph (507 kph), almost six times faster than Crichton’s Great Train Robbery train. Lockheed’s L-749 Constellation, which first flew in 1947, was even faster at 345 mph (555 kph). Such speeds, combined with the airliners’ ability to stay aloft for hours without refuelling, offered a mixed blessing: for the first time in history, while human beings could cross oceans in a matter of hours, the effort was exhausting, and very expensive.

From the very beginnings of the industry, airlines survived largely because of lucrative contracts to carry mail, but they also did everything possible to convince potential passengers that flying was the best way to travel. Some early airliner cabins came to resemble luxurious steamship interiors. In 1939, Pan American Airways, whose fleet consisted of large flying boats, tried to emulate ocean liner service by calling its aircraft “clippers” and requiring its flight crews to wear uniforms reminiscent of naval officers’ uniforms, with white hats, navy-blue, double-breasted jackets, and rank insignia on the sleeve cuffs — four stripes for captains and three for 1st officers. Other airlines followed suit.

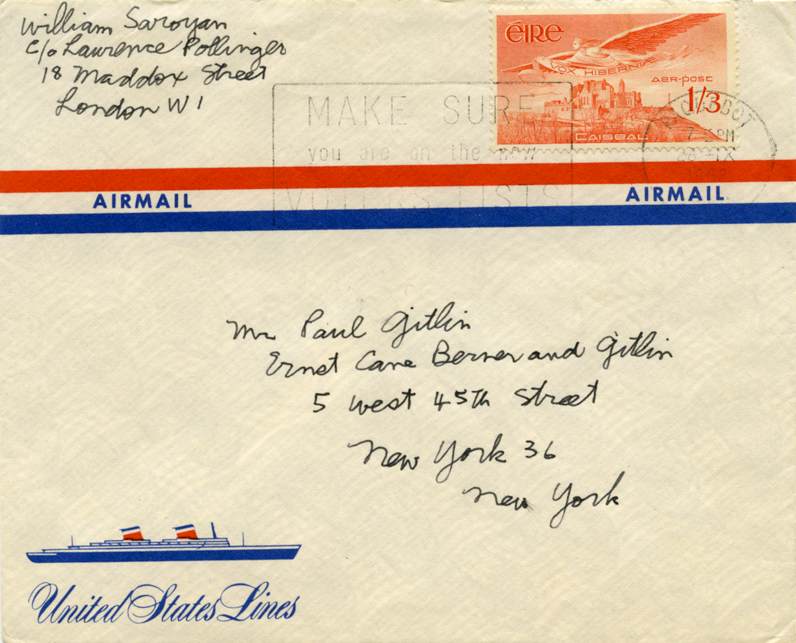

Curiously, even some shipping lines promoted airlines even while they were losing passengers to them. In 1962, William Saroyan, the Pulitzer Prize-winning American author and playwright, posted a letter while he was onboard the United States Lines ocean Liner S.S. America, enroute to the U.S. to Bremerhaven, Germany. The airmail envelope he used was provided by the shipping company. America had stopped at Cobh, Ireland, which explains the Irish stamp.

Except for their far-greater speed, no airliner ever offered the luxurious travel experience that ocean liners offered, but they did their best. Passengers could drink as much alcohol as they wished, and smoke the free cigarettes and cigars that were offered: every seat included a built-in ashtray. Pillows and blankets were available for those who wished to sleep. And every seat had something that everyone appreciated but few people can afford today: lots of leg room! But that expansive leg room wouldn’t last. Every “newer, bigger, better” airliner reduced the amount of leg room that passengers had: the DC-7, which replaced the DC-6B on many routes, was just six and a half feet (two metres) longer than the DC-6B, but had “room” for 16 more passengers! And now more than ever, of course, passengers travelling in economy class on on long-haul jet flights, generally feel like sardines in a can, and at the end of a long flight may smell like sardines in a can!

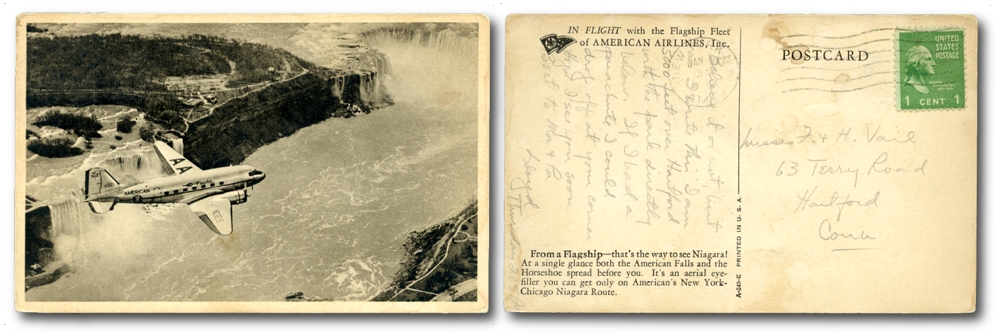

Some airlines, recognizing that long flights could be boring, experimented with in-flight movies as early as 1921, but not until the 1960s could passengers routinely expect to see current feature-length films on long-haul flights, although “adult films” banned. Many airlines provided free colouring books to children as well as postcards and pencils or pens so that passengers could write in-flight messages to their earthbound friends and relatives, encouraging them, the airlines hoped, to recommend their service. The cabin crew would collect the completed postcards and the airline would affix stamps at no cost to the passengers and mail them at their next stop. It’s not uncommon to find used postcards with messages like this one:

Of course, in order for individual airlines to get passengers, they first had to convince them to buy tickets. In 1950s and early 1960s, airline advertising slogans promised speed, safety, comfort, reliability, and even relaxation:

Speed Safety Comfort / Anything, Anytime, Anywhere, Professionally / Airline of the Executives / The airline you haven't been waiting for / Land in your hotel / Fly with Stop-Watch Reliability / Save time - Save money Fly Braniff / The ontime airline / Experience Inspires Confidence / Route of the Timesavers / Please - no dancing in the aisles

In the 1950s, Eastern Airlines, an American airline which operated primarily on the U.S. Eastern Seaboard, extolled its services in a flyer published in the 1950s:

The airlines also took full advantage of an experience that ocean liners could not provide and few people, seeing the earth from the air.

Good intentions aside, and despite the most glowing of advertising slogans, airlines relied on the fact that airliners provided what ocean liners could not — greater speed than any other conveyance in world history had ever offered. Nevertheless, passengers who chose airliners over ocean liners faced the reality that airplanes fell from the sky with far greater regularity than ocean liners plunged to Davie Jones’ Locker.2

Until the development of the first commercially successful jetliners — the DeHavilland Comet and the Boeing 707 — propeller airliners had routinely flown into often-angry skies and often came to grief simply because their pilots couldn’t see the violent storms and dangerous winds that they were approaching, much less climb above them: the term “anvils of the gods” refers to the term pilots use to refer to spectacular, flat-topped cumulonimbus storm clouds which can climb as high as 66,000 feet (18,288 metres) into the atmosphere, more than twice as high as the service ceiling of the DC-6B airliner that often climbed to altitudes that the airliners could not reach, and challenge even jet pilots. Not until the 1970s was airborne radar capable of notifying airliner crews that they were approaching potentially deadly weather systems.

A flat-topped cumulonimbus capillatus incus cloud — an “anvil of the gods” — flattens itself against the troposphere in this American Airlines postcard, picturing a DC-6 airliner.

Weather radar installation wasn’t until 1947. As previously mentioned, radar was initially used onboard aircraft for tactical purposes, with the weather being more of a nuisance rather than the desired target. This began to change as the utility of weather detection became more apparent during and after World War II. The primary weather concern for aviation was severe weather, namely thunderstorms, which along with their associated turbulence, hail, lightning, and heavy precipitation were one of the leading causes of crashes at the time. In 1945, U.S. airlines began to explore the use of airborne weather radar. Between 1945 and 1946, Trans World Airlines (TWA) worked with Bell Labs and West Electric to assess primitive weather radar on board a C-47 (DC-3) aircraft. From 1947 to 1949, American Airlines also flew radar-equipped C-47 aircraft with AN/APS-10 radar to detect and study thunderstorms in the Denver area. Further research conducted by United Airlines led to the idea that radar was critical to aviation safety.

The first commercial aircraft with airborne weather radar was a DC-6 that took flight in 1950. United Airlines named their radar systems “Sir Echo,” complete with its own logo. The availability of airborne weather radar was quickly adopted as a marketing tool, assuring passengers of improved rides and increased safety. Following a series of crashes suspected to be associated with convective weather as well as the technological strides being made in radar systems, the FAA began to require weather radar for all air carrier aircraft, a precedent that remains to this day. A 1955 study by United Airlines found immediate dividends to the radar requirement. The company reported a sharp decline in static discharge events and a decrease in turbulence incidents as well as less time spent in bumpy conditions. Further, there were 80 percent fewer weather incidents reported by flight crews as well as a reduction in delays and detours.

Some of the worst aviation tragedies resulted not from bad weather but from from two aircraft coming to grief in midair collisions.3 Not until the late 1980s was anti-collision radar capable to notifying airliner crews that they were in imminent danger of colliding with other aircraft.

The complex, capricious reciprocating engines that powered airliners until the introduction of turbojet and turboprop engines were noisy and had a bad habit of catching fire in flight, or simply quitting. Among the “more exciting” incidents occurred were those involving propellers that suddenly when propeller blades or even entire propellers suddenly took leave of their engines. A few tragedies occurred when propeller blades separated from the engines and slashed into airliner fuselages. Some multi-engine airliners could fly even if they lost one or more engines, adding excitement to routine flights.

Even in the absence of storm and mechanical failures, long-distance airliner flights were (and still can be) exhausting. Airliners commonly failed often failed to take off on time because of mechanical problems, airport congestion, and bad weather. Occasionally, airliners had to make emergency landings far short of their destinations, or might be forced to land at alternate airports when conditions prohibited landing. Timely arrivals could be sabotaged by fog, storms, high winds, wind shear[^4], other air traffic, wind shear, bird strikes, in-flight mechanical failures (stuck landing gear, engine fires), or illness or even death of pilots.

Even today, the most dangerous periods of any flight occur during takeoff and the climb to cruising altitude, and, especially, the landing. It took decades of experience for the aviation industry to understand that wingtip vortexes created by planes that are taking off can destabilize aircraft that follow in their wake. Since the timely arrival at their destinations was vital to the to an airline’s success, delays only hurt their image and sometimes led to cases of the aforementioned press-on-itis.4

As they approached New York’s Idlewild Airport, the crew of LAI Flight 451 would fall victim to the industry-wide tendency to stick to the schedule as closely as possible, even if it meant making multiple risky approaches despite bad weather. The result would be a disaster for nearly everyone on board.

[^4] Wind shear refers to a brief change in the direction and force of wind moving horizontally or vertically. It is a serious concern for aircraft in the moments before landing because it can push an aircraft off course or cause a sudden, unexpected stall. Wind shear, now detectable by radar at larger airports, has been blamed for several fatal accidents.

HOME | Next Page: What went wrong?

-

“Press-on-itis” is a psychological condition common to Western societies, driven by the widely expressed need to get a task — any task — done in a timely manner. Other terms for this condition, common in aviation but rarely expressed openly, include “hurry-up-itis,” “get-home-itis,” “hurry syndrome,” “plan continuation,” “goal fixation,” “time-urgency,” or “time sickness”. Press-on-itis results from a form of magical thinking that involves continuing toward a destination or objective despite a lack of readiness and the availability of lower-risk alternatives. In aviation circles, press-on-itis often occurs when circumstances such as bad weather or ↩︎

-

Davy Jones' Locker, a metaphor for the bottom of the sea is used as a euphemism for drowning or shipwrecks in which the sailors' and ships' remains are consigned to the depths of the ocean (to be sent to Davy Jones' Locker). The origins of the name of Davy Jones, a sailors' devil, are unclear. A 19th-century dictionary traces Davy Jones to a "ghost of Jonah". ↩︎

-

In 1954, a Canadair Trans-Canada Airlines Northstar airliner, a variant of the Douglas DC-4, collided with a Royal Canadian Air Force Harvard trainer over the city of Moose Jaw, Saskatchwan, killing all 31 passengers, the four TCA crew members, the student pilot of the Harvard, and a woman on the ground when one of the Northstar’s Rolls-Royce Merlin engines fell on house she had been hired to clean. It was the worst aviation accident in Canada up to that time. See my web page, North Star Falling. ↩︎

-

Early on Christmas morning, 1954, a week after LAI Flight 451’s flight from Rome to New York City, a Boeing B-377 Stratocruiser flown by British Overseas Aircraft Corporation (BOAC) between London and New York City, crashed at Prestwick, Scotland, killing 28 of its 36 passengers and crew. The captain, William L. Stewart, survived and was blamed for "errors of judgement,” but Capt. Stewart's son, Malcom, an actor in Vancouver, told the author of this web page in an email that he was sure that his father fatigued because of unavoidable flight delays and too many hours in the cockpit. One cause of the crash, detailed in my web page, Christmas Tragedy at Prestwick, was almost certainly “press-on-itis”. ↩︎