PAYDAY AT WOODFIBRE (Part 4) — Japanese Canadians, defined as “enemy aliens,” suffer internment and loss of jobs and property

Japanese at Woodfibre

In 1941, in Woodfibre’s Japanese employees and their families enjoyed lives that were at least partially integrated with those of white employees and their families.

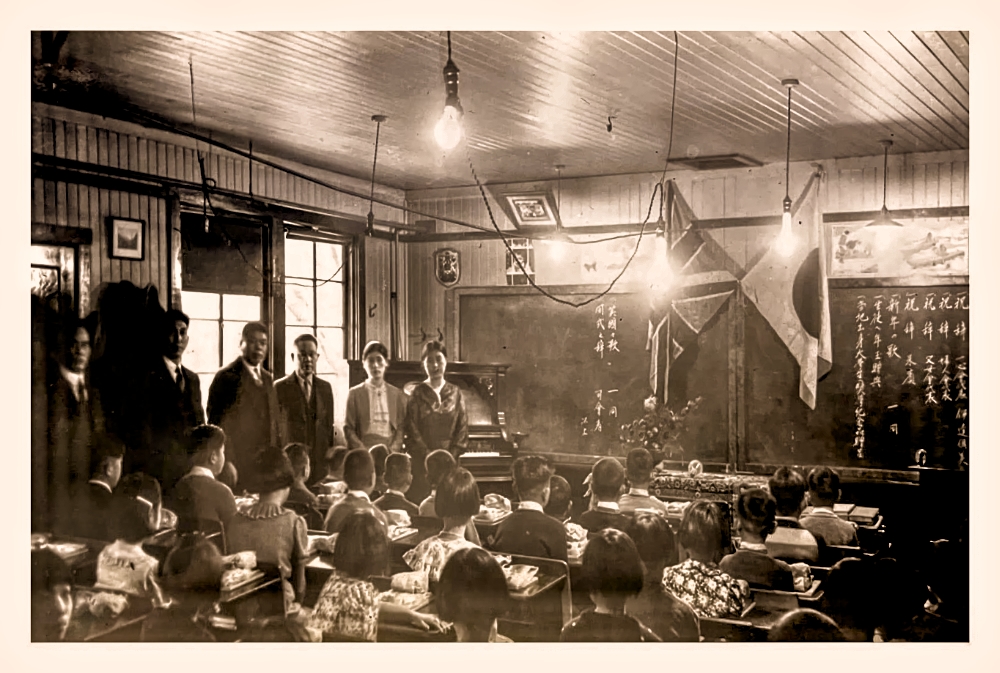

There was a “Japan Town” at Woodfibre, complete with houses, dormitories, a cookhouse, a store, and a school for primary students. Japanese residents took an active role in community life, and older students attended an integrated school with the children of white employees. There were apparently no East Indian employees.

Dorothy Golden, who was a school-age child living at Woodfibre in the late 1930s, recalls only one Chinese, Lee Jack, who worked as a servant for the mill manager, Edward Brennan, and his family at a guest house. Lee Jack’s grandson, Patrick Lee, who lived in Woodfibre after the war, confirmed Dorothy’s memory, and added that his grandmother was the custodian at the Woodfibre school. Lee Jack died in 1963.

Memories of a Japanese Woodfibre employee

Takeo Ujo Nakano, a Japanese employee at Woodfibre in the years before the Second World War, was among the first Japanese to be “evacuated” from Woodfibre and interned. In 1987, the Woodfibre Times published his memoir of those years:

An anxious, frightening future

I had immigrated to Canada in my late teens and had spent most of the next twenty years as a millhand for the Woodfibre Pulp and Paper Company. … It was my fate to be parted from my wife and our eight-year-old girl, to face what seemed to be an anxiety-filled and frightening future.

An idyllic town

Woodfibre, population 1,000, was an isolated company town up coast from Vancouver. The Japanese population was about five hundred including women and children. Woodfibre remains in my memory as an idyllic town where Japanese lived in their tight little community in one section, and an equal number of whites living in their community in another section.

An idyllic town

I accepted the fact that the whites were the elite. Their men were paid more than us when they did the same jobs. Mainly, of course they held the better jobs. Very few Japanese immigrant workers spoke English. It was the Japanese contractor who spoke English, who negotiated with the company and who decided who should be hired.

Amicable relationships

There was amicable, if not close relations between the Japanese community and the white. The regular point of contact between them was a weekly baseball game which took place each Sunday afternoon from spring into summer. Each team cheered enthusiastically for their team. The high point of the year for the Japanese community was the annual Christmas variety show in which the drama group presented such traditional plays as "The Forty-Seven Ronin". The honoured guest was the company manager, Mr. E.P. Brennan, truly a great friend to the Japanese. His warm speech initiated a most pleasant evening. And he shook hands with many of us as he left the hall.

Nature’s “secret hiding place”

…One event stands out in my mind, the occasion of the celebration of the coronation of King George VI. The Japanese committee was responsible for organizing the celebration in which the whole town participated with fanatic fervor. It began with a big children’s masquerade parade in the afternoon. A variety show followed in the evening. The whole community — Japanese, whites, men, women, and children — was infected by the festive mood; such an outpouring of loyalty, high regard, and fond wishes for our new sovereign was surely not surpassed elsewhere in Canada. But I think Woodfibre is nearest to my heart in her quieter moods. It seemed nature had picked this place to be her secret hiding place and I was privileged to share it.

War brings a bleak future to Japanese Canadians

On December 7, 1941 a large force of Japanese bombers attacked Pearl Harbor. The Canadian government immediately declared war on Japan and passed an order-in-council identifying Japanese Canadians, including those born in Canada, as “enemy aliens”.

By the following March, an estimated 22,000 Japanese Canadians, most living and working in British Columbia, had been ordered to leave their homes and report for transportation to internment camps in BC’s interior, east of a quarantine zone that extended 100 miles from the Pacific coast. Many were sent into the Okanagan region in southern BC or to Alberta to work as agricultural labourers.

The Canadian government shut down all Japanese-language newspapers, took possession of businesses, fishing boats, vehicles, houses and personal belongings — and sold them in 1943 at prices far below market value.

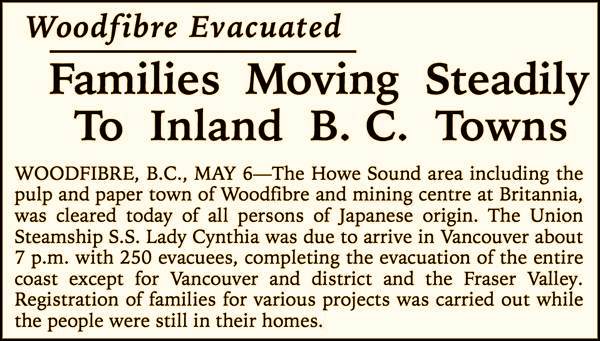

The government’s actions against the Japanese were hardly a favour for BC’s forest industries, which were already suffering manpower shortages. Great Central Sawmills on Vancouver Island had employed Japanese almost exclusively in its drying kilns, except for management; the Japanese community at Great Central Lake totalled 58 people. In the spring of 1942, they were gone, along with all Japanese employees and their families from pulp mills in Ocean Falls, Port Alice, and Woodfibre.

On May 6, 1942, the New Canadian, an English-language newspaper that addressed the concerns of Canadian-born Japanese, reported the story about the Woodfibre “evacuation”:

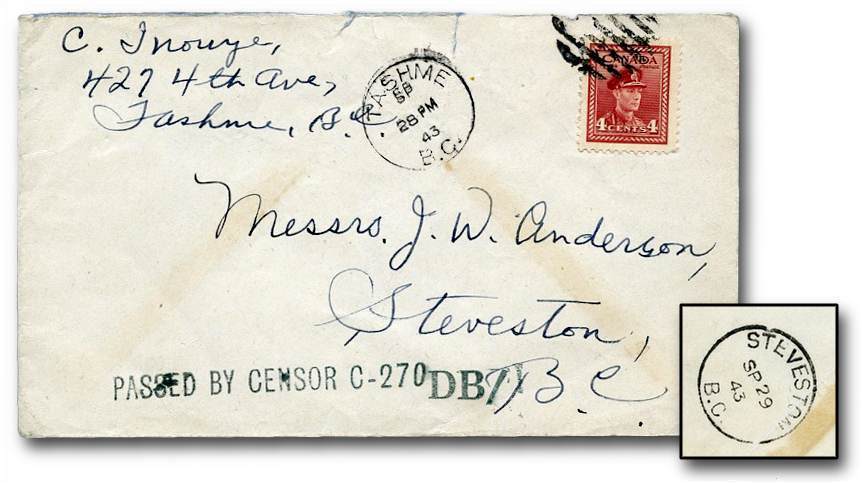

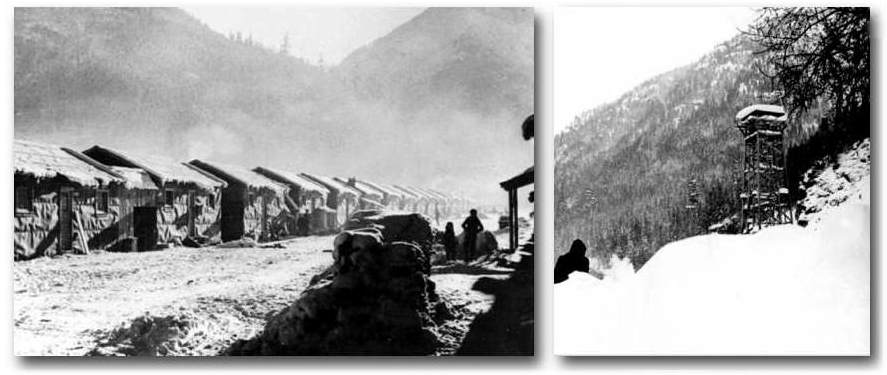

One of the “communities” that was established for Japanese internees was at Tashme, BC on the Crowsnest Highway between of the town of Hope (on the Trans-Canada Highway) and the entrance to Manning Park in the Cascade Mountains of British Columbia. Tashme, just outside the 100-mile quarantine zone, housed 2,400 people on the site of a former Depression-era relief workers' camp. Japanese men housed at Tashme were employed in highway construction. After the war, when internees were released, Tashme was renamed Sunshine Valley; today, local businesses cater largely to tourists.

Middle- and upper-class families who were not deemed to represent a security risk were placed in euphemistically named "self-supporting projects" or "relocation centres"; the internees were allowed to leave the camps, if granted permission, but since they weren’t allowed to work outside the camps or attend school, the great majority elected to remain in the camps (some of which had to be built from the ground up by the internees themselves).1

Complaints were dealt with harshly

It was risky for internees to complain too loudly. Some 700 “complainees” found themselves imprisoned in POW camps in Ontario for the duration of the war. Among them was Takeo Ujo Nakano, mentioned previously as a Japanese employee at Woodfibre. Nakano protested his internment, a protest that earned him transport to an internment camp in Ontario, where he spent the rest of the war, without his family. Nakano tells the story of his internment in his book, Within the Barbed Wire Fence: A Japanese Man's Account of his Internment in Canada, published in 1980.

In effect, the internment utterly destroyed a segment of Canadian culture. At the same time, it helped pave the way for modern Canada. Despite our society’s lingering prejudices and instances of xenophobia, we have become a cosmopolitan nation which could be — and should be! — the model for many less-enlightened nations.

In April 1945, the Canadian military suggested to the RCMP that Japanese Canadians should be interrogated about the balloons. The RCMP replied that any assumption that the Japanese maintain an espionage network in Canada “has no foundation and cannot be entertained in light of our experience.”

Next, in Part 5: With their Japanese employees interned by the Canadian government, and their remaining workforce of Caucasion menreduced by voluntary enlistments in the military, British Columbia's pulp and paper mills employ significant numbers Chinese men, some Caucasion women (for the first time), as well as more East Indians.

-

Which begs this question: Since Japanese Canadians weren’t weren’t security risks, why were they interned in the first place? The answer, of course, is that prejudiced leaders always camouflage their prejudices by inculcating unreasoned and unreasonable fear in members of their own race.

As late as April, 1945, five months before VJ Day, the Canadian military suggested to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police that Japanese Canadians should be interrogated about fire balloons that had been launched from the Japanese island of Hokkaido towards North America; the balloons were intended to start forest fires, a plan that incidentally failed. The RCMP replied that an assumption that Japanese Canadians maintained an espionage network “has no foundation and cannot be entertained in light of our experience.” (Source: “Our History: The War with Japan,” by Eric Andersen, writing in the Aug. 24, 2013 edition of the Squamish, BC Reporter) ↩︎