PAYDAY AT WOODFIBRE (Part 5) — Internment of BC’s Japanese Canadians provides forestry jobs for Chinese workers

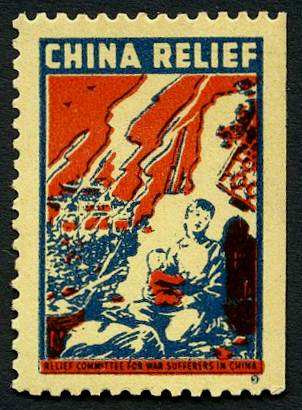

The internment of BC’s Japanese Canadians, not to mention the war itself, conferred blessings of sorts upon British Columbia’s Chinese Canadians:

☛ Chinese no longer had to compete with Japanese for jobs.

☛ White Canadians left their jobs in droves to join the military when the British Commonwealth declared war on Germany in 1939. Now, in 1943, Canadian industry, short handed but geared up for the production of war materiél, turned increasingly to the labour pool provided by ethnic Chinese, Sikhs and other East Indians, and women.

☛ Chinese Canadians suddenly found that they had at least one thing in common with white Canadians: China and Chinese, with Canada and Canadians, were allies in the fight against their common enemy, Japan.

Although the Republic of China was little more than a passive ally, it was an ally nevertheless: It was actually fighting two wars, one against the Japanese, and the other against the Communist forces of Mao Zedong (also transliterated as Mao Tse-tung).

Only 12 days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the 1st American Volunteer Group, nicknamed the Flying Tigers, serving as a unit of the Chinese Air Force, flew combat missions against the Japanese. Their well-publicized successes gave hope to Americans that they could eventually win the war. Subsequently the Republic of China allowed the Allies to establish airfields in China, from which attacks on Japanese forces and on Japan itself could be mounted.

Chinese civilians helped to rescue 72 of 80 American air crew who had attacked Tokyo in the famous Doolittle Raid. Flying B-25 bombers from the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Hornet, the planes struck targets in Japan, then flew on to China where the crews bailed out or the planes crash landed. The Japanese killed an estimated 250,000 Chinese in reprisal.

Wartime manpower shortages in BC’s forest industries

It’s not known how many Japanese employees worked at the pulp and paper mill at Woodfibre before the war, but there were probably a few dozen, at least, and the mill could scarcely afford to lose them. Since the beginning of the Second World War, in September, 1939 BC’s forest industries had been losing its white employees in wholesale numbers; they had either joined the military or moved on to more lucrative jobs in other industries.1

To make up for such shortfalls, Woodfibre and other mills in the province hired not only more Chinese workers to replace their interned Japanese workers, but more East Indians, and for the first time, women. In 1942 the Woodfibre mill imported 36 French Canadian workers. The priority was the production of pulp and paper, which in modern warfare is at least as important as bullets and bombs; as Canada fought for survival against the Axis powers, who made pulp and paper was far less important than whether it was made.

Most of BC’s Chinese forest employees were bachelors. Because of the imposition of high “head taxes” in 1902, the cost of bringing a wife or aged parents to Canada became prohibitive. In 1931, out of a total Chinese population of 46,519, only 3,648 (just over 8%) were women. In the late 1920s, it was estimated that there were only five married Chinese women in Calgary and six in Edmonton.2

The lives and working conditions of Woodfibre’s wartime Chinese employees have scarcely been documented. They lived in dormitories, and were isolated to some degree from the mill’s white employees and their families if only because of the wide gulf created by differences in language, social customs, religion, and even food. After all, Chinese had never been fully accepted by white British Columbians.

An integrated school

The children of white employees at Woodfibre remember with fondness their Japanese classmates, and they remember the empty seats left behind, seats which were not filled by Chinese students, but with the children of white workers, assuming that mill management managed to find sufficient numbers of workers to replace the Japanese. For the duration of the war, and well beyond, school photographs taken at Woodfibre would no longer be “multicultural,” but uniformly white.

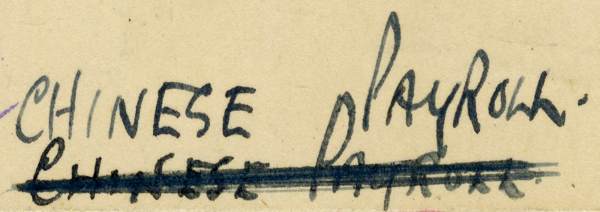

Chinese workers resist union membership

There is evidence that Woodfibre’s Chinese employees were not isolated from the industrial community at Woodfibre, and in fact had a voice: In 1944, the International Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulphite and Paper Mill Workers (IBPSPMW) organized a membership drive for employees at Woodfibre. Ninety per cent of white workers joined the union, but union organizers were less successful with the mill’s Chinese employees. Despite the efforts of Thomas Wong, a Chinese organizer, and the fact that union literature had been translated into Chinese, only 45 of the mill’s 150 Chinese workers — 30 per cent — joined the union. That statistic, perhaps, is a clue to the meaning of the “CHINESE PAYROLL” notation on the shipping tag which spurred the creation of this web page.

A tong at Woodfibre?

Early in the history of Chinese immigration to North America, discrimination against Chinese forced them to organize self-protective societies called tongs. In Chinese culture, the word tong means "hall" or "gathering place". In North America a tong is a type of organization found in Chinese communities. These organizations are described as secret societies or sworn brotherhoods and have historically been tied to criminal activity. Today tongs are, for the most part, members of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Associations, which are pro-Kuomintang (Nationalist Chinese) groups providing immigrant counselling, Chinese schools, and English classes for adults.

It doesn’t seem possible that a tong could possibly co-exist with management at Woodfibre, which was an isolated, company-owned town subject to a strict paternalism that kept a tight grip on employee activities and barred outside influences that weren’t deemed to be in the best interests of employees. So, if there wasn’t a tong at Woodfibre, how can the “CHINESE PAYROLL” notation on the Bank of Nova Scotia shipping tag be explained? The answer might be in the Portuguese word comprador.

If not a tong at Woodfibre, a comprador?

The word comprador means buyer; it derives from the Latin comparare, to procure. The original usage of the word in East Asia meant a native servant in European households in Guangzhou in southern China or the neighbouring Portuguese colony at Macao who went to market to barter their employers' wares. The term evolved to refer to native contract suppliers who worked for foreign companies in other countries.

In British Columbia, compradors commonly served as collaborators or intermediaries in commercial transactions between Chinese employees and companies in fishing and forest industries. It is possible — even likely? — that a Chinese employee had been designated as a comprador for Chinese employees at Woodfibre? It would have been a rare Chinese employee who was literate in English, nor is it likely that their employers and fellow workers were literate in Chinese; a comprador would have been able to speak and write both English and Chinese, and would have been paid, either by the company or the Chinese workers themselves, to help them in their business and personal affairs.

Change in postwar Canada

The end of the Second World War resulted in sweeping changes to Canadian society, although hostility towards Asians, especially Japanese, remained high.

Goodbye to the “Head Tax”

In 1947, as signatory of the the United Nations' Charter of Human Rights, the Canadian government had to repeal the Chinese Exclusion Act, which contravened the UN charter. In 1947, Chinese Canadians were finally granted the right to vote in provincial and federal elections. However, it took another 20 years for a points system to be adopted for selecting immigrants, allowing Chinese to be admitted to Canada under the same criteria as any other applicants.

Born in Canada, but “repatriated” to Japan

Japanese Canadians did not fare so well. Even before the war ended, Canadian politicians were demanding the deportation to Japan of all Japanese Canadians. A questionnaire designed to identify "disloyal" Japanese Canadians gave them a choice between moving east of the Rockies immediately or be "repatriated" to Japan at the end of the war. Some 10,000, chose deportation. Many chose to go to Ontario, where they could work in agriculture, but they were met by prejudice: white-collar jobs were not open to them, and men who had been skilled in various fields were reduced to minimum-wage manual labour.

When Japan surrendered in August, 1945, thousands of internees balked at the idea of resettling in the war-torn country, but their requests to avoid repatriation were denied, and deportations began in May, 1946. Thousands of nisei (ethnic Japanese born in Canada) were sent to a country they had never known and where they would be alienated and not treated as equals by the Japanese.

Fortunately, public attitudes towards the internees had softened somewhat since the start of the war. The Cooperative Committee on Japanese Canadians protested the deportation, and in 1947 the government relented and allowed those still in Canada to remain. It was too late 3,964 Japanese Canadians who had already been deported "back" to Japan. Only in April, 1949 were all restrictions lifted from Japanese Canadians still in Canada.

Compensation (of a sort) for internees

A royal commission in 1947 examined the issue of compensation for confiscated Japanese property, eventually awarding $1.3 million in claims to 1,434 Japanese Canadians, or less than $1,000 per claimant. Claims based on loss of property were accepted; all other claims were refused.

Concerns surrounding the internment of Japanese Canadians also led to changes to Canadian immigration policy, with corrective legislation gaining momentum after a statement made by Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King on May 1, 1947:

Large-scale immigration from the Orient would change the fundamental composition of the Canadian population….The government, therefore, has no thought of making any changes in immigration regulations which would have consequences of the kind.

Not until 1962, however, was legislation passed that eliminated racial discrimination in Canada’s immigration policy.

Conditions for Chinese employees following the war were no doubt much the same as they were during the war, although there were many fewer Chinese employees, no doubt because returning servicemen got preferential treatment. In a Facebook message, Patrick Lee said that when his family lived at Woodfibre, from 1957 to 1969, they were the only Chinese family in town, along with individual Chinese men living alone in the bunkhouses, including two that he named — Benny Wong & Tommy Kang. “[It was] very strange indeed,” Patrick said, “and although I have good memories of Woodfibre...racism was pretty normal and acceptable behaviour right into the 1960s.”

He added, “My grandfather had it very hard with the racism, my father less so, and me...much, much less. In Woodfibre it was mainly bullying and racist comments...I fought a lot. You kind of felt powerless.”

Next, in Part 6: In the years following the Second World War, Japanese- and Chinese-Canadians and East Indians are accepted as full-fledged Canadian citizens, but British Columbia's vibrant pre-war Japanese community never recovers. Improved transportation and a growing movement against corporate paternalism results in closure of the Woodfibre townsite. The Woodfibre pulp mill itself closes permanently in 2006, almost a century after it opened. In 2013, Woodfibre LNG (Liquid Natural Gas) Limited signs a purchase agreement with Western Forest Products to acquire the Woodfibre property. On Friday, February 6, 2015, Woodfibre LNG Limited officially becomes the owner of the Woodfibre site.

-

An interesting case in point was the situation at the Ocean Falls pulp and paper mill, where about 850 workers were employed. In the first 10 months of 1943, the company hired 983 men, but in the same period 1,108 men quit their jobs, leaving the company short-handed by 125 employees. ↩︎

-

Source: “Chinese Canadians” in the Canadian Encyclopedia. ↩︎