North Star Falling — Death rains from the sky over Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan (Part 3)

The collision between a Trans-Canada Airlines North Star and an RCAF Harvard trainer over Moose Jaw has roots in one of Canada’s most significant contributions to the Allied war effort against Nazi Germany, the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, more commonly known by it’s initials, BCATP, or simply “The Plan”.

The BCATP is born

When Great Britain and its dominions declared war on Germany in 1939, military air crew were in short supply. Canada, Australia, and New Zealand joined the mother country to establish the BCATP, the goal of which was to train air crew for combat.

The BCATP, the largest aviation training program in history, was responsible for producing nearly half the pilots, observers,1 air gunners, wireless operators and flight engineers who served with Commonwealth air forces.

The “Right Stuff”

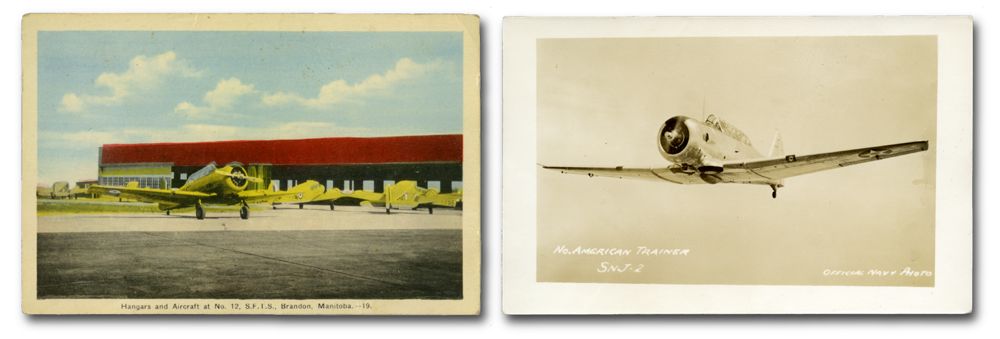

Following basic training, student pilots who exhibited the “Right Stuff,” received training at one of fifteen Service Flying Training Schools — SFTS — across the nation, where they made the transition from low-powered primary trainers like the Fleet Finch and de Havilland Tiger Moth to a powerful, high-performance advanced trainer, the North American Harvard Mk. II. Later, in the cockpits of Supermarine Spitfires and the Hawker Hurricanes, they would face the best aircraft and pilots of the German Luftwaffe, and win.

Moose Jaw became one of 15 Service Flying Training Schools, SFTS #32. The BCATP was so successful that it was cancelled in 1944, after more than 167,000 air crew had been trained and deployed to British, Canadian, New Zealand and Australian squadrons.

The North American Harvard trainer

By early 1940, the RCAF had obtained 1,200 Harvard Mk. IIs, Anglicized versions of the U.S. Army Air Force AT-6A Texan and the U.S. Navy SNJ. The Harvard Mk. II had a more-powerful engine than the Mk. I, an all-metal fuselage rather than the original tube and-fabric fuselage, and redesigned rudder. The web site of the Canadian Museum of Flight notes that the Mk. II “…was one of the most important single-engine training aircraft of the BCATP. It was known as ‘the pilot maker’ because of its important role in preparing pilots for combat.”

Harvards fly into the Cold War

At the end of the Second World War, the RCAF sold most of its Harvard trainers, which was a bad decision since the Cold War came hard on the heels of the Second World War. By 1949, the RCAF was again in need of trainers; 100 T-6J Texans were leased temporarily from the USAF and a further 270 Harvard Mk. IVs were ordered from Canadian Car & Foundry, Thunder Bay. The RCAF used its Harvards for a further fifteen years — they were, of course, being flown from Moose Jaw — finally retiring them in 1966.

Next, in Part 4: Thirty-seven people — the crew of four and 31 passengers on the North Star, the young English pilot of the Harvard, and a cleaning lady on the ground — go blithely on with their lives, unaware that death is imminent.

-

Observers in Commonwealth air forces of the Second World War descended from air crew in the First World War whose job was to observe and photograph the enemy from air, and bomb them if possible. By the Second World War, observers had taken on the role of the navigators and bombardiers, and sometimes operated defensive machine guns. ↩︎