MSgt. Phil Ingraham’s War Stories (Part 1)

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor ends American isolationism

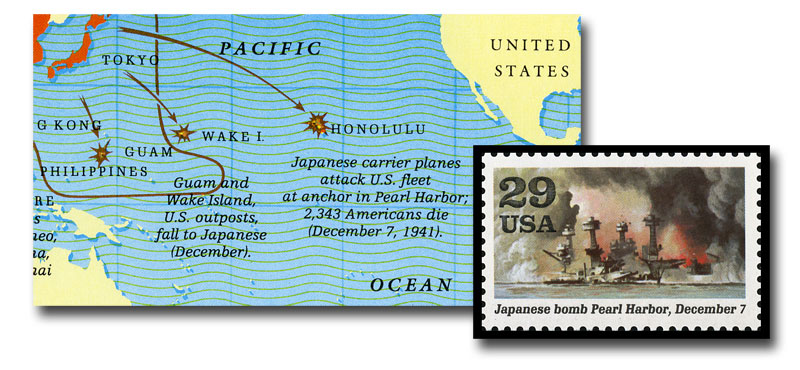

The United States declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941, the day after Japan attacked the American naval base at Pearl Harbor. On the same day, Japanese forces also invaded several other American military establishments in the Pacific, including the island of Guam.

It wasn’t just the attack on Pearl Harbor that was a surprise: most Americans weren’t even aware that there was a naval base at Pearl Harbour. Most, along with many politicians, had ignored the war in Europe, hoping to maintain the isolationism that had been America’s hallmark since the First World War, which ended in 1918. Fortunately, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was well aware of the possibility that America would have to go to war again. He had quietly taken important steps to aid Great Britain and Russia in their fight against Hitler and Mussolini, and to prepare his country for war.

Despite Roosevelt’s preparations, the United States was spectacularly unprepared for war. It was widely feared that Japan, having dealt the U.S. Navy a staggering defeat at Pearl Harbour, would soon launch an invasion of the American mainland. That did not happen. The peacetime, Depression-ridden economy turned almost overnight into a wartime economy, and young men who had been contemplating jobs and marriage and family life soon began donning uniforms by the tens of thousands. My uncle, Philip Ingraham, was among them.

The Marines turn down a good man

When Pearl Harbour was attacked, Phil was 25 years old and still living at home with my grandparents (not an unusual situation in the years of the Great Depression). He had a good job (he was a letter carrier for the post office), and was engaged to be married. Like tens of thousands of his countrymen, however, he felt compelled to join the fight. On January 2nd or 3rd, 1942, less than a month after the U.S. declared war on Japan, he went to the nearest Marine Corps recruiting office. His recorded narrative starts at that point:

There are probably two points in a soldier’s life, in the time he spends in the service, especially during wartime… which you’ll never forget. You’ll never forget the day you left home and you’ll never forget the day you came home….

I do recall very well and vividly going to the recruiting station in Elmira, New York, and completely flunking the Marine physical test due to three little things that normally nobody would pay any attention to. I guess they wanted the esprit d’corps to continue on, so they turned me down. I went right across the aisle to the Army Air Corps recruiting station; he put his hand under my chin, the doctor did, looked at me all over, up and down a little bit, to say ‘You’ll do fine.’ I figure that that was the shortest physical ever given in the history of the armed services. There might have been shorter ones, but I don’t know how unless the doctor waved to them out of a window.

A bleak future

Phil was told to report back on January 11th — little more than a week to say his good-byes. It must have been an emotional time for his family and friends and his fiancée, Bea. The future looked bleak: events in Asia and across Europe, and in North and East Africa, had shown Americans that their new enemies were ruthless, almost inhuman, or perhaps all human in their eagerness to destroy not just individuals but whole societies. The odds of survival for the average soldier seemed slim, not to mention the survival of entire nations.

Not that Phil was necessarily frightened. Young men don’t waste much time worrying about dying: they are too eager to live, too dedicated in their search for adventure. Phil’s first adventure in the Army started the moment he marched into his induction centre at Fort Niagara, near Youngstown, N.Y., where thousands of Western New Yorkers had their first taste of army life:

I was 25 at the time; is there ever a greater confusion in the mind of a young man than when you do finally end up in an induction centre and you are number so-and-so and that’s it? There is no describing it, no way in the world….

I recall around a thousand men without a stitch of clothing on and about 25 doctors going down through the ranks and giving physicals and all that.

I don’t know where Life Magazine was in these cases, but they wouldn’t have printed a picture if they’d taken it. I don’t believe in any young man’s life that there could be anything quite as humiliating as the standing out in the cold, up at Fort Niagara, one foot, dancing up and down, and on the other foot, dancing up and down, with a thousand of your future buddies all doing the same thing. It was really something else, and it does stay in your memory, there’s no doubt about it!

Learning left from right & how to salute,

or not learning very much at all

They taught you many things at Fort Niagara: I say ‘many things.’ I’ll alter that. A few things. One of them was how to make an Army bed, and make a half dollar bounce if you dropped it, bounce up high enough so you could catch it on the rebound. And another one was how to be out of bed in 10 seconds, stand by the bed, and salute. And in all that time never waste a motion. You learned that too. I swear they deliberately marched officers through there just to keep you getting out of bed every once in a while. You lay back on the bunk bed to get a little rest there and Whoa! Some colonel would come marching through. ‘Attention!’ …

That went on for a couple of days. Then they assigned you a drill sergeant and 20 or 30 of you went out and learned your left foot from your right. Some of the sergeants they had there looked to me like they didn’t know their right from their left, or anything else for that matter. Oh, they weren’t such a bad bunch of guys, and I can understand why anyone who thought they were going to be stuck at Fort Niagara for any length of time would take on a terrible, awful attitude…. But I don’t think they were half as bad as they sounded. I found out later that they weren’t, of course.

I don’t know how many thousands of men were going through Fort Niagara every day, but if you ever saw coal going down a chute, that’s the way they were moving them in and moving them out. They never gave you a chance there, you know; all of a sudden you found yourself at a table taking some kind of an IQ test or something else, and immediately you were hustled somewhere else…. You didn’t get an opportunity to absorb that much of it….