MSgt. Phil Ingraham’s War Stories (Part 6)

Back in January of 1942, Phil had tried to join the Marines. He flunked his physical, but if he had succeeded he might well have been one of those fighting the Japanese in the jungles of Guadalcanal. He could have become one of that battle’s many casualties: 1,600 Marines killed, 4,400 wounded.

Instead, Phil found himself among the 90 per cent of soldiers working in a support role for the 10 per cent of the GIs in various—and dangerous—combat roles. That, however, did not mean that Phil could relax: on two occasions, not to mention the times he came under Japanese artillery fire, he thought he had ‘bought the farm.’

Close call at Bougainville

Since Phil’s job involved flying from one island to another in a combat zone, often at night, it was inevitable that his routine might occasionally be frightening, or downright terrifying. Phil recalls a flight to Bougainville: The B-25 was being flown by Phil’s commander. On board were the co-pilot, a navigator, the crew chief, Phil and three other radio repairmen.

“The navigator found the island o.k.,” Phil explains, “but somebody forgot to mention to him that on the other side of a huge mountain chain from our forces were the Japanese forces. The Japs had taken a hell of a shellacking but were still not completely subdued.”

Phil could hear the cockpit chatter through earphones. As they were making their approach to the airfield, he could see activity and thought, “Oh boy, when these wheels come down, we will be home safe,” realizing at the same time that any island shared with the Japanese Army could hardly be considered safe.

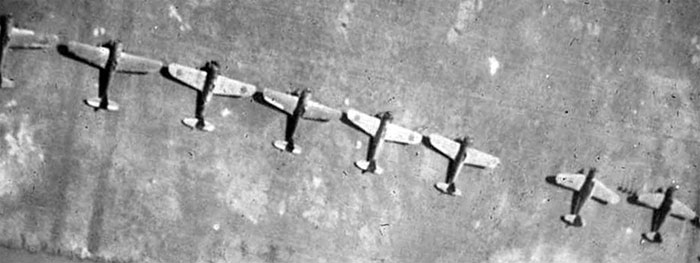

Suddenly, he heard, amid loud expletives, “Get the hell out of here! It’s theirs! It’s a Jap airfield!” Someone had made a serious miscalculation: the crew was lost, and at the airfield directly ahead, lined up neatly along the runway, were rows of Japanese Zero fighters.

Phil told himself, This is it, we’re never going to make it! But the colonel put the B-25 in a steep climb at full power, and Phil swears that if you looked straight down out of that B-25, you would have seen the rudder assembly. Eventually, they found the American-held airfield and landed safely.

Lost over the Pacific — at night!

Phil vividly remembers vividly another incident, perhaps less dramatic than the one at Bougainville, but no less dangerous. He and his crew had been to New Georgia, north of New Caledonia, and were returning to Guadalcanal through skies that were still contested by Japanese fighters. Phil’s description puts you right there in the plane with him:

We left the island about 4:00 p.m., and two New Zealand fighter planes escorted us down through what they figured was a pretty tricky zone to be flying in — in an unarmed B-25. So they kept up beside us. Every now and then the pilots would wave at us. Then they gave a great big salute — you could see ’em, they were that close to us — and they turned around and went back.

Here we are, out over the Pacific. The sun is setting. I thought, Boy, I don’t like this. I don’t like it a bit in this cottin’-pickin’ B-25! And you know you begin to get a little bit panicky, but we were purrin’ along, and we were due in there I think about eight o’clock at night, and we got just about halfway back and I noticed that the navigator ducked up to the little passage — you had to crawl through a passage above the rear of the plane to get to the pilot and co-pilot — and we saw him going up there…. His chart table was right behind us, and the co-pilot came back. He said, ‘Do you think you can zero us in?’ And the navigator said, ‘I don’t know. There’s something radically wrong here in my readings, and I can’t find them.’ He was lost. The navigator was lost!

Here we are in the South Pacific, with about two and a half or three hours to go, with no way in the world of defending ourselves. The pilot let us sweat for about half hour. He was doing circles. The pilot was circling, not to get any further off than he was before. Finally they managed to hook onto a beacon signal from one of the other islands there — I don’t know where it was from — and the guy was able to correct himself. But he did say later, ‘If you think you were worried, what do you think I was?’

By this time, Phil was beginning to get philosophical. He remembers thinking, Well, what the heck, you know, you can’t last forever.

Phil joins the Australian Air Force

In a curious twist of war, Phil and his team of radio repairmen became temporary members of the Australian Air Force, and were sent to Australia for special training. “The Australians had devised a whole new system of direction finding equipment,” he explains. “It was a life-saving expedient for a lost pilot. Three stations would simultaneously take a bearing on him...and they knew very close to where he was at that time, and they sent rescue out.”

Phil continues:

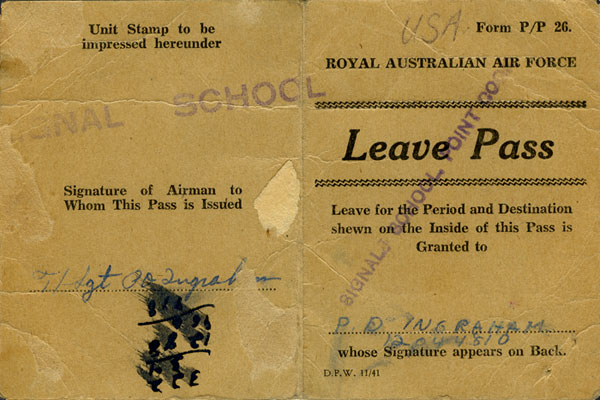

We were transferred from the U.S. Air Corps — barracks bag, clothing, every part of us was transferred to the Royal Australian Air Force. We no longer were under the discipline of or in the pay of or anything else of the U.S. Air Corps….It was a Lend-Lease Deal.

So, off to Australia. Oh wow! We were down there about nine weeks, taking their course at the Signal School at Point Cook, which was quite an experience. We hadn’t been near civilization for quite some time at that point, and there was a nice group of boys there, and we had a lot of fun, along with the going to school there, at Point Cook, not too far from Melbourne….

We did the old tip-your-hand-up salute that comes from the British, and we were under the discipline of the Royal Australian Air Force. If we did something wrong — we tried not to of course; under these circumstances, we might never get home — if we did anything wrong the discipline would have come from the Australians. They were tough….

Incidentally, the triangulation system was used later at Noumea, and it did save several pilots’ lives. We were very happy about that.