MSgt. Phil Ingraham’s War Stories (Part 5)

Phil arrives at Guadalcanal

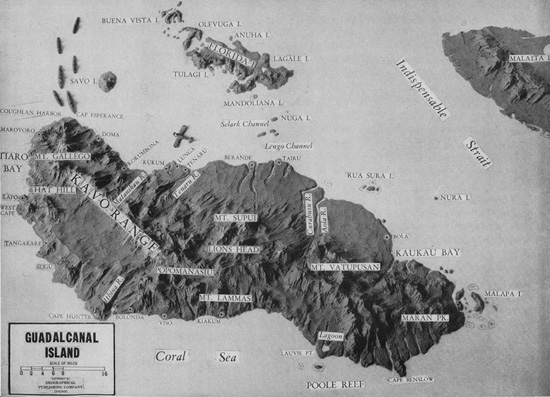

Phil had arrived at Henderson Field, Guadalcanal, the largest of the Solomon Islands, an archipelago in the Southwest Pacific about 1,900 kilometers (1,200 mi.) northeast of Australia.

Guadalcanal is a big island, of 2,510 sq mi (6,500 sq km), characterized by a mountainous, volcanic terrain, tropical heat and humidity, and thick jungle. On August 7, 1942, the U.S. Marines stormed ashore in the first American land assault against the Axis. The legendary American victory did not come until March 6, 1943: 1,592 soldiers & marines were killed in action, 4,183 were wounded, and thousands more were disabled for varying periods by disease. Japanese losses were staggering: 14,800 killed in battle, another 9,000 dead from disease, and about 1,000 taken prisoner.

The war become real

It didn’t take long for Phil to learn firsthand that the battle for Guadalcanal was not over:

The second night we were at Henderson Field another fellow and myself were operating side by side in the operations tent, and I was having a chance to use my knowledge of the Morse International Code, and he also was an operator. The two of us were operating there and the air raid siren sounded. We’d been told where to go. We had a doggoned shelter there — not a shelter, it was a ditch in the ground, that’s what it was, with some logs thrown over and some dirt thrown on them, and there was usually about three inches of water in the bottom of it — and the air raid sirens sounded and one guy pointed, ‘This way fellows!’ and we dashed over into this place and I sat down on a log that was in this place and my feet were in water up to my ankles. This happened several times, but fortunately the bombs were dropping around us and none of them hit any closer than half a mile, something like that.

I understand one bomb struck a hospital unit there one night. I don’t know how badly it was damaged. The odd part of it was that it got to be such a common thing that you didn’t talk about it much the next day. You didn’t ask questions about it, you just went about your business and that was it. But we did learn one very important thing: After a raid is over you didn’t immediately eject yourself from the foxhole or the shelter or whatever. You waited awhile, because flak [from anti-aircraft shells] has a habit of falling back to earth and it would really do as much damage to you as a bomb would do if it ever hit you direct.

While Phil himself survived the war without a scratch, he did come face to face with the men who became its victims:

There was an artillery group on the island, and they were practicing there…. They used to practice during the day and during the night we’d hear the whistle of the artillery shells as they went overhead. Of course we got kind of used to it — you know, you can get used to anything if you’re tired enough — and it really wasn’t that bad. They were firing from far enough way that the sound of the guns themselves wasn’t that bad. It was the sound of the swish — swish — swish of the shell going overhead. One particular night they were practicing and it kind of kept you awake a little bit, but I had dropped off to sleep and suddenly the old earth just roared, and I was virtually tipped out of my bunk, and I thought Oh boy, what’s this one, hey, it’s here, it’s here, Boy, you’ve had it. And it was an awful flare of light off towards Henderson Field, towards the field itself, towards the runways, and something very bad had happened there….

We found out the next day that two New Zealanders were taking off for somewhere. I don’t know where they were going, but they did have a thousand pounds of bombs aboard, and they hit the deck on takeoff and the bombs blew up.

The next morning, Phil needed to go to the dispensary, where he saw the pilots. He says he doesn’t know whether they lived, but he did not see how they had even survived. He describes the burns as hideous, the smell as indescribable. “That in itself sobered up quite a few people that were around there, like myself, who hadn’t really seen with our own eyes what these things can do.”

While Guadalcanal served as Phil’s introduction to the war, his job as a radio repairman would take him all over the South Pacific. At Tontouta Air Base on the island of New Caledonia, his skill with International Morse Code once again determined his role in the war.

Unarmed in a combat zone

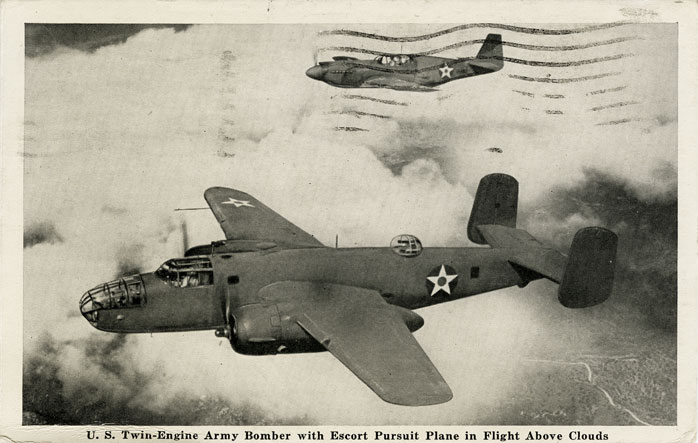

Throughout most of Phil’s assignment in the Pacific, he was a member of unit of radio repair unit. The men were provided with an unarmed B-25 bomber to transport them to a list of destinations that reads like a tourist’s diary: New Hebrides, Efate, Espiritu Santos, Tanna, Noumea.

At the time, there was a scarcity of radio operators skilled in the use of Morse Code, which was vital in the war effort. Two-way voice communication by radio was largely in its infancy, and, a great deal of radio communication throughout the war depended on Morse Code. Phil’s work at New Caledonia involved the establishment of a school for radio operators. (Morse code has long since disappeared from commercial and military long-distance communication, but hobbyists still learn and use it.)

For more than two years, Phil and the other technicians would fly endlessly from one tiny island to another to another, repairing and maintaining the radios of the AACS. It wasn’t glamourous work, but the war couldn’t have been won without them. Radio was the only efficient means of communication between military bases that were separated by hundreds or even thousands of miles of ocean, and an absolute necessity for navigation. Eventually, Phil would become directly involved in Australian direction-finding research that would save hundreds of downed Allied pilots. In fact, for a short period, he would be transferred to the Royal Australian Air Force.