MSgt Phil Ingraham’s War Stories (Part 8)

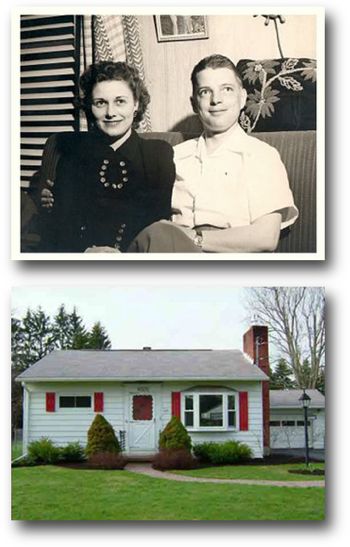

Uncle Phil moved smoothly from military to civilian life, taking up residence with Bea in Painted Post, New York, where they joined the First Presbyterian Church.

Phil became a technician at nearby Corning Glass, and Bea went to work for the Ingersoll-Rand corporation in Painted Post, N.Y. and stayed for 33 years. She spent 26 years in the Cost Department before taking early retirement. In her last seven years, she worked for the director of industrial relations, first as his private secretary for two years and then his executive secretary.

Phil and Bea lived in several apartments in the decade following the war, and then in 1955 built their own house, at 175 Deerland Avenue, in what Bea characterized as a wonderful neighbourhood, one that they would never want to leave. They would live there together for the next 56 years, with the exception of a brief stay in a nursing home while they both recovered from medical problems.

Bea and Phil adopt a daughter

Bea and Phil did not have children of their own, but a child, Bea’s young cousin Sandra Brooks, came into their lives. Bea and Phil saw Sandra frequently while she was growing up, and became very fond of her. In 1962, when Sandra graduated from high school, Bea and Phil asked her to come and live with them and offered to send her through college.

She accepted, and went on to earn a nursing degree from Corning Community College. She went to work in Corning Hospital and spent 30 years there, retiring at age 50 as vice president in charge of quality assurance and risk management.

Phil and Bea legally adopted Sandi — who had changed her name from Sandra — in 1982, choosing Ingraham as her middle name. In that same year, Sandi married John Slater.

No lack of illness, trauma, and tragedy

Chronic and acute illness, trauma, and sometimes tragedy seem to be inevitable in the human experience, but Phil and Bea seem to have suffered far more than their fair share.

Electrocution

Phil barely survived an industrial accident at work in 1975; both shoulders were broken and muscles in his arms and chest were ripped apart by a powerful electrical shock. He had to have prosthesis in his right shoulder and a plate in his right arm. He retired with a small disability pension in 1976.

Death visits twice on the same day

The darkest day in Bea and Phil’s life came on Nov. 10, 1997. Bea lost her mother, Mildred Jackson, on that day. Mildred was 94 years old; when she died at 12:30 p.m., Bea, Phil, and Sandi were at her bedside. Then, unbelievably, at 9:30 p.m. that same day, Sandi suffered a catastrophic stroke and died three hours later. She was 53. “We loved Sandi as we would have if she had been our own daughter,” Bea said. “We had some wonderful times together and we wouldn’t trade all those great memories for anything.”

At the left, Sandi Ingraham Slater and Mildred Jackson, photographed at the Hilton Hotel in Corning, NY, in 1990.

Bea suffers a heart attack, a brain aneurysm, and post-op complications

More problems were in store. In 2000, Bea was operated on for a fast-growing brain aneurysm. Pre-operative tests showed that she had also suffered a mild heart attack, but surgery could not wait. Surgeons repaired the aneurysm in an eight-hour operation, but Bea’s prognosis was poor: the surgery had probably caused severe and permanent brain damage.

Then came post-operative complications, including a collapsed lung, blood clots in the lung as well as both legs, and an onset of exceptionally high blood pressure. Three times Bea was taken to the ICU, and three times she went home. A miracle had occurred, or perhaps several miracles, and by Christmas she was on her way to a complete recovery in both body and mind.

Phil deals with near blindness, and iliac aneurysm

Bea’s illness naturally caused a great deal of stress for Phil, whose vision had become severely impaired over the years by macular degeneration. During Bea’s hospitalizations, Phil almost had to be physically forced to stay with friends.

Next, it was Phil’s turn, when in 2006 he developed a iliac aneurysm that required minimally invasive surgery (although “minimally invasive” in this context is a shockingly bad joke). He never fully recovered from that surgery, but he and Bea continued to live full lives for several more years.

A sad turning point

2010 proved to be a sad turning point for Phil and Bea. In November, Phil was hospitalized briefly for congestive heart failure, pneumonia, and kidney problems, not to mention a probable heart attack, and Bea suffered painful injuries from a previous fall. For a few months, they lived in semi-private accommodations at a nursing home. Homesickness and concerns about the high cost of the nursing home sent them back home to 175 Deerland Avenue early in the spring of 2011.

In November, 2011, Phil fell at home, fracturing his right hip and his right wrist in three places. Surgery was successful, but the next day he fell again, breaking his left arm so badly that surgery could not make it functional again. It was placed in a cast, but the day after his cast was removed, he fell yet again, re-breaking his left arm. (The falls were occurring in part because of dementia; Phil couldn’t understand why he had to remain in a wheelchair when he was not in bed.)

The four fractures took their toll on Phil’s already-limited physical resources. In December, 2011, he was transferred to Founders Pavilion extended care facility in Corning. Dementia, a concern in previous months, gradually became more evident.

Phil never left Founders. Bea visited him virtually every day for the next 15 months, despite her own increasing infirmities. During this period, their neighbours, Don and Sis Krebs, proved to be real-life angels, helping Bea with all aspects of her life and frequently taking her to visit Phi. Another good friend, Gloria Morrison, also offered invaluable help to Bea.

Phil dies at age 95

Phil’s physical health gradually deteriorated, and his dementia worsened, but only in the final few days of his life was he unable to communicate. Early in the morning of Friday, March 23, 2012, he slipped away. Phil and Bea would have celebrated their 70th wedding anniversary on Sept. 26, 2012.

On March 24, the Corning Leader published his obituary. An estimated 70 mourners attended Phil’s memorial service, held March 29 at the First United Church in Painted Post.

Gary A. McCaslin, Pastor of the First Baptist Church of Painted Post, gave the eulogy, which presents an accurate characterization of Phil Ingraham.

Military service in the Second World War defined much of MSgt. Philip Ingraham’s post-war life, and was solemnly noted at his memorial service with a 21-gun salute and the presentation to Bea of the American flag that had flown during the salute.

Although Phil was not directly involved in combat in the Pacific, he was unavoidably exposed to the havoc it wreaked on combat veterans. One experience in particular left him with an indelible and troubling memory, and strong feelings about the insanity of war. In his recording, he offered these final thoughts:

When I left Guadalcanal, my commanding officer needed me in a hurry to go to Efaté in the New Hebrides because of a shortage of men there in our particular line of work… He was willing to take any form of transportation that the U.S. Army Air Corps was willing to throw at him, and he called and said that the only thing they had going was some wounded going out that afternoon, and they would be stopping at Efaté….

The plane was loaded with men whose minds had snapped in battle. There must have been at least 20 men, in terrible shape. I’ll give you an example. One of the men was stretched out on a litter, and he looked over at me and he said, ‘Who are you?’ ‘Well,’ I said, ‘I’m a fellow soldier. I’m on my way to Efaté.’ ‘Oh!’ he says, ‘You’re lucky! You’re talking to Harry James, the trumpet player!’ Others were unconscious, in a state of suspended animation, men mumbling things over and over. There was nothing phony about these men. They were in bad, bad shape.

I’ve often thought that that was the capping climax in my feeling: Here was a group of boys, they’ve all got parents, even though they’re going to go home sometime, to what and with what, with broken-hearted parents, wives, sweethearts, all for what?

Now I’m not questioning the war at all. You have to come down to earth and say, well, common sense says we were hit and we had to hit back, and that’s true. I’m not going to deny that a bit. But I do say to myself, What were the circumstances many, many years ago that triggered this sort of thing? What kind of story has the other fellow got to tell about his reason for being in the war? The Germans, the Japanese, what have you, and I often got to thinking, Wait a minute, I don’t think that fellow wanted to go to war any more than I did. In fact, I’m sure of it. It’s foreign. It’s foreign to anyone….